The dam on McKinley Lake, Rattlesnake Wilderness. Photo credit: Peter Whitney/City of Missoula.

Answering the Dam Question: Visitor Perspectives on Removing and Maintaining Dams in Wilderness

by WILLIAM L. RICE and CHRISTOPHER A. ARMATAS

Science + Research

April 2024 | Volume 30, Number 1

Abstract

Managers of designated wilderness in the United States are challenged by the complex issue of how to address existing dams and water storage. Dams can exist in wilderness, as they are considered a special provision that can provide a variety of benefits to society; however, dams are also considered a potential threat to wilderness character. We review the issue of dams in wilderness, and then present the results from a study in the Rattlesnake Wilderness in Montana where visitor opinions around dam removal or maintenance were assessed. Our aim through this present research is to examine public agreement or disagreement with removing or maintaining dams in a federally designated wilderness. The findings demonstrate a nuanced perspective among visitors, with support for assessing dams on a case-by-case basis and recognizing the importance of managing wilderness for climate change resiliency.

Keywords: dams; Rattlesnake Wilderness; special provisions; visitor survey; water storage

Dams have largely been characterized as antithetical to wilderness. In his influential and now-famous 1955 essay “Marks of Human Passage” in opposition to dams in Dinosaur National Monument, Wallace Stegner puts the two in direct opposition. Scholars frequently cite high-profile dam controversies of the Hetch Hetchy Valley, Glen Canyon, Grand Canyon, and Echo Park as key catalysts of the modern wilderness movement (e.g., Harvey 1991; Nash 2014). Yet, according to Zellmer (2012), approximately 200 dams are located within the bounds of federally designated wilderness areas in the United States (all of which were built prior to designation or were built on previous dam sites existing prior to designation); 144 dams existed in the initial 9.1 million acres of wilderness designated with the passage of the Wilderness Act in 1964 (Gunderson and Cook 2007). Most of these dams were constructed to increase the water storage capacity of existing lakes (Nickas 1999). Concerning the Wilderness Act, dams are generally considered to be detriments to wilderness character as they constitute development in wilderness and trammel hydrological and ecological processes (Nickas 1999). In special provisions listed in section 4(d) of the Act, however, it is stated that:

The President may, within a specific area and in accordance with such regulations as he may deem desirable, authorize prospecting for water resources, the establishment and maintenance of reservoirs, water-conservation works, power projects, transmission lines, and other facilities needed in the public interest.

While the president has not yet used this provision (as of 2012), it has been utilized by Congress when designating new wilderness areas with existing dams (Nie and Barns 2012).

Our aim through this present research is to examine public agreement or disagreement with removing or maintaining dams in a federally designated wilderness. The conundrum concerning how to reconcile existing dams in wilderness has led to varying outcomes. The Tin Cup Dam in the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness has previously been maintained with motorized equipment and – in at least one instance – using heavy construction equip- ment that was airlifted to the site (Nickas 1999). The Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness has a storied history of dam maintenance and reconstruction – even going as far as replacing the early rock and timber Prairie Portage Dam with a concrete dam in 1975 (Proescholdt 1985). However, more recently, a US district court found that the decision of the US Forest Service to repair dams in California’s Emigrant Wilderness was “clearly” contrary to the provisions of the Wilderness Act (Carsley 2013, p. 549). The resulting 2006 decision instructed the US Forest Service to let the dams decay naturally (Zellmer 2012).

Interestingly, in October 2009, the National Park Service removed the Lower Glenbrook Dam on the Estero de Limantour within the bounds of Point Reyes National Seashore’s Phillip Burton Wilderness. The project was initially proposed to restore ecological and hydrological processes, mitigate a public safety hazard, remove a nonconforming structure from the wilderness, and restore the natural character of the wilderness (National Park Service 2009). However, climate change was also cited as a key consideration throughout the project’s review process. In the National Park Service’s “Basis for the Decision” resulting from the NEPA process, the agency states that the action will “better enable the estuary and surrounding natural resources to adapt to potential impacts of Global Climate Change, including sea level rise” (2009, p. 17). The dam was removed in one week using an excavator, dump trucks, bulldozers, and other mechanized equipment (National Park Service 2009).

The ecological restoration and climate resiliency reasoning invoked in the Phillip Burton Wilderness example is also alluded to in the US district court’s decision concerning the Emigrant Dams. Although concluding that support of recreational fishing was not an appropriate purpose, the court noted that dam maintenance may be justified based on the restoration of native trout populations (Long and Biber 2014). In the Phillip Burton Wilder- ness, it was determined by the agency that the dam should be removed, in part, to support ecosystem restoration. However, the courts suggest that dams in the Emigrant Wilderness might be maintained for similar reasons of ecosystem restoration, if appropriate.

Climate change introduces new challenges to wilderness management, which have been noted for well over a decade (Graber 2011; Long and Biber 2014; Stephenson and Millar 2011; Zellmer 2012). Principle among these challenges is the conundrum of how to address the impacts of climate change on wilderness character. As asked by Stephenson and Millar (2011), “If untrammeled was meant to refer to an absence of intentional human influences, what are we to make of pervasive unintentional human influences, like anthropogenic climatic change?” (p. 34). The authors conclude that when assessing the trade-off between natural and untrammeled aspects of wilderness character when faced with accelerating climate change, it is expected that justification for intervening (or trammeling) will increase over time (Stephenson and Millar 2011). Thus, Nie and Barns (2012) contemplate the future role of the special provisions granted to the president in section 4(d) of the Wilderness Act concerning the establishment and maintenance of reservoirs in the face of climate change. They cite the case of the proposed San Juan Mountains Wilderness Act of 2011 wherein the US Forest Service opposed measures in the bill to prohibit water development projects. Other authors have also highlighted that – despite the Wilderness Act’s reputation as being largely inflexible – the act’s limited “flexibility” is well positioned toward climate adaptation (Long and Biber 2014).

Importantly, as others have noted, this flexibility may be utilized as a means of translocating species in need of climate refugia (Appel 2015; Camacho 2010). For example, Galloway et al. (2016) developed a framework for managers to use when assess- ing the feasibility of transplanting threatened fish populations into historically unoccupied lakes and streams with the aim of providing climate resilience. They tested this framework in an evaluation of translocating threatened bull trout upstream to formerly unoccupied climate refugia – a trammeling action that managers then undertook in 2014 within an area managed as wilderness in Montana’s Glacier National Park. However, as found by Watson et al. (2015) through a study of visitor attitudes toward management intervention to adapt to climate change in Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks’ wilderness, there is an apparent conflict between the perceived naturalness dimension of wilderness and support for intervention to adapt to climate change. The authors’ findings highlight that individuals’ understanding of wilderness is both highly complex and variable across individuals and social groups.

Thus, given the nuance concerning the human construct of wilderness character and the role wilderness might play in a warmer, drier Anthropocene, perspectives on the management of dams in wilderness may prove useful in understanding visitor support for possible management actions. Therefore, we have developed the following research ques- tion in service of providing such insight: How does agreement for removing or maintaining wilderness dams vary based on the reasoning provided concerning wilderness character and climate change?

Methods

Study Site

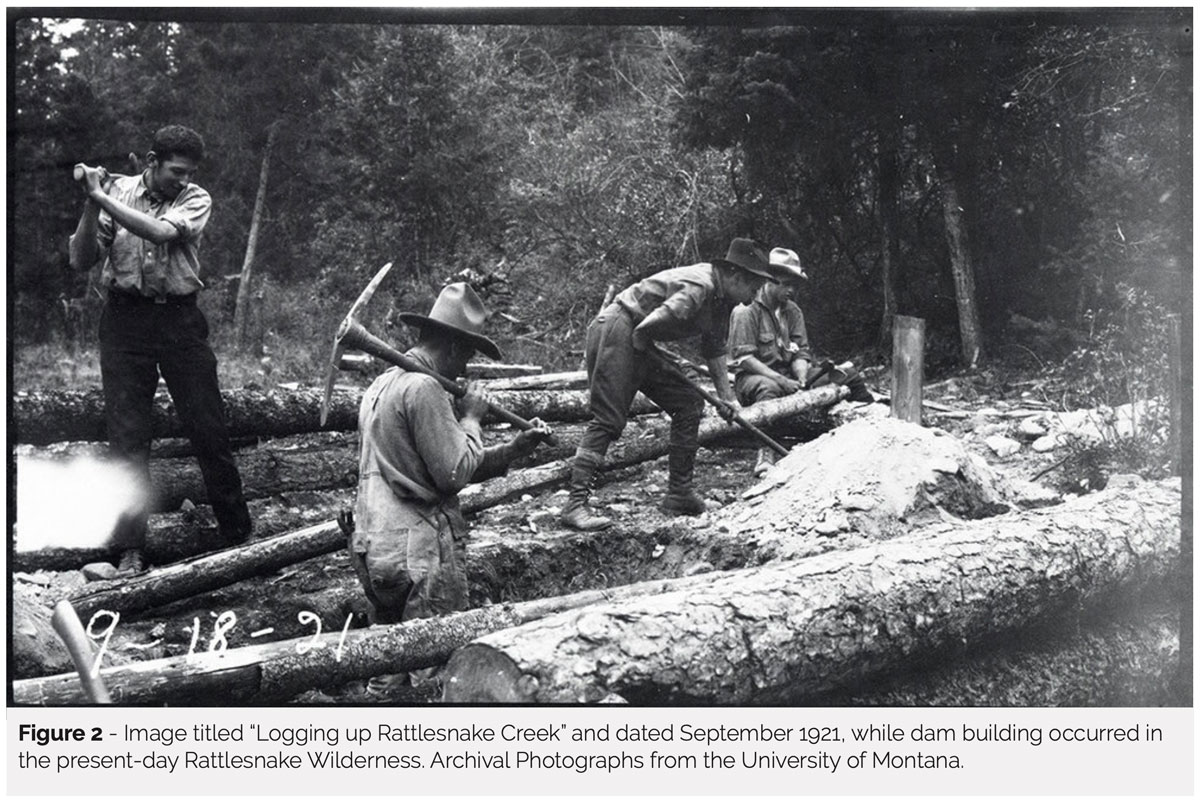

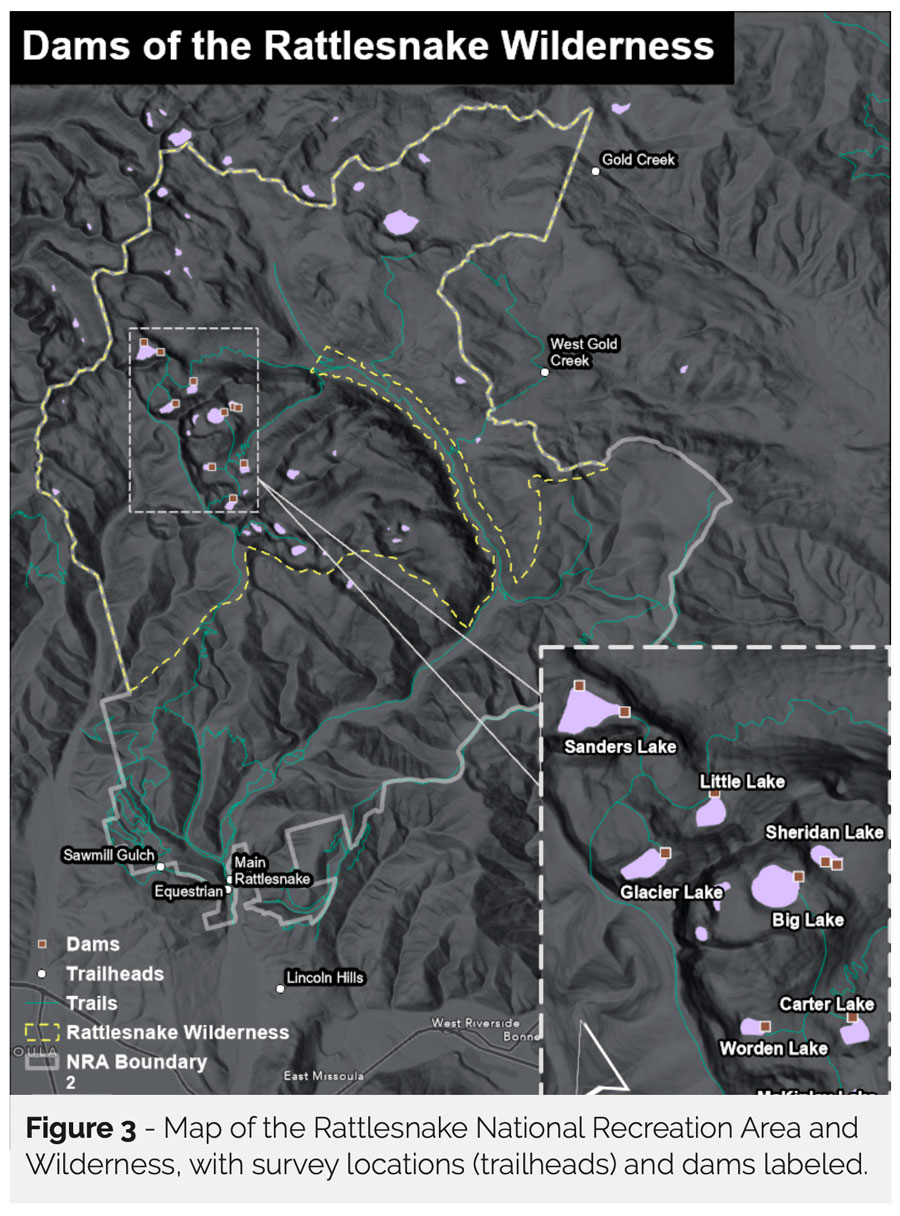

We examined our selected research question in the context of the Rattlesnake Wilderness. The Rattlesnake Wilderness is located within the Rattlesnake National Recreation Area on the Lolo National Forest in western Montana. Designated in 1980, the Rattlesnake Wilderness encompasses much of the headwaters of the Rattlesnake Creek watershed, a municipal watershed in the City of Missoula, Montana. Séliš and Ql‐ispé people have occupied the watershed since time immemorial, and the importance of Rattlesnake Creek is reflected in its name – N‐‐ay Sew‐k ‐ s (small bull trout’s waters). Today the watershed provides important habitat for bull trout, listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. The wilderness offers year-round opportunities for backpack- ing, ultrarunning, fishing, alpine ski touring, and long-distance day hiking. The wilderness contains numerous high mountain lakes, eight of which were dammed by the Montana Power Company (who later sold the dams to the Mountain Water Company in 1979) between 1911 and 1923 to increase water storage capacity (Chaney 2021). The Rattlesnake National Recreation Area and Wilderness Act of 1980 alludes to the dammed lakes in section 1(a) as “water storage” and “clean, free- flowing waters stored and used for municipal purposes” – although it does not reference the dams directly.

In 2017, the City of Missoula acquired ownership of the dams from Mountain Water Company (Chaney 2021). In recent years, the City of Missoula; Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks; and Trout Unlimited have recognized the resiliency potential for some of the larger dams in the Rattlesnake Wilderness. They can provide climate resiliency for threatened bull trout by storing cool water deep in their reservoirs through the winter and spring and releasing it into Rattlesnake Creek tributaries during drier, hotter summer months (Evans 2022). This would require maintaining, and potentially rebuilding, at least one existing dam (Evans 2022). In 2018, the city and the US Forest Service began a planning process concerning the future management (removal or maintenance) of the wilderness dams. To inform that planning process, the City of Missoula sought visitor input concerning the future management of the dams.

Survey Preparation

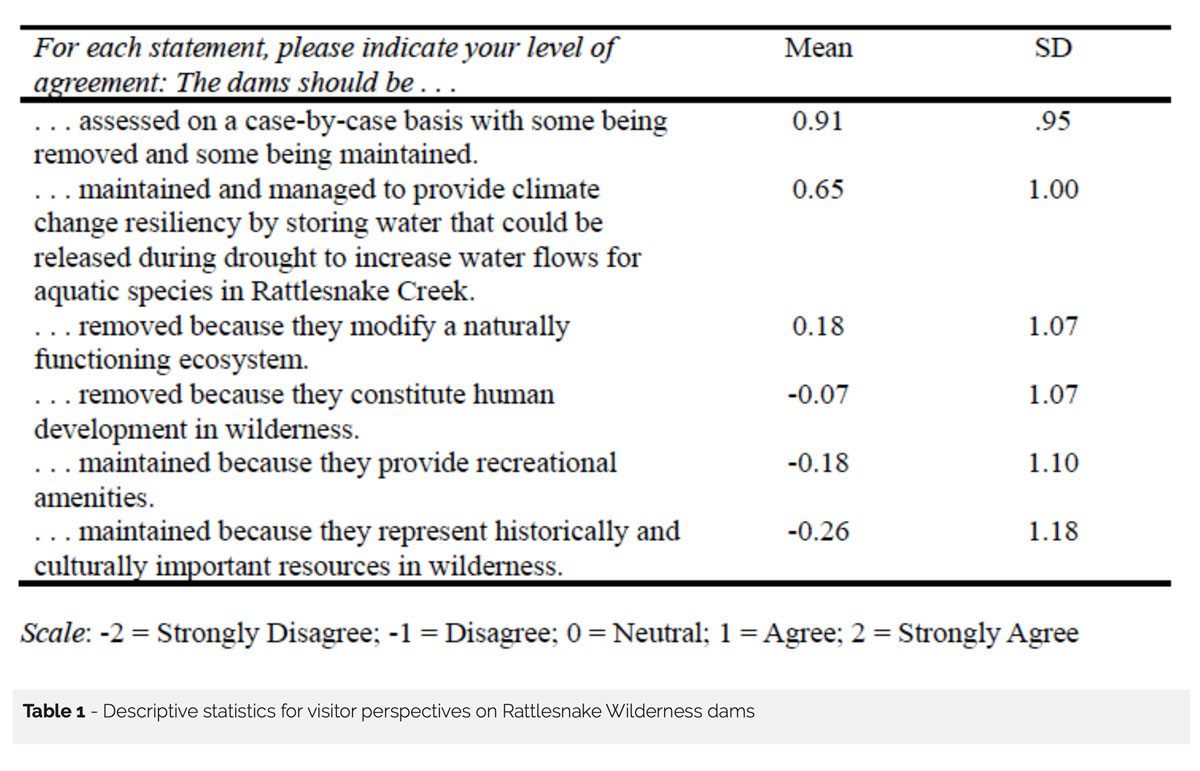

Six statements (Table 1) were developed collaboratively between the research team, US Forest Service Wilderness staff, and City of Missoula Conservation Lands staff through a process where scenarios and justifications for removing or maintaining the dams were developed. Additionally, the following statement was developed as a means of ensuring survey respondents received official language developed by US Forest Service and City of Missoula staff to inform them of the dams’ history and management prior to responding to the statements:

The Rattlesnake Wilderness contains 10 dams built on 8 high mountain lakes in the headwaters of Rattlesnake Creek. Rattle- snake Creek was the original water supply for early settlers in Missoula, and the dams were constructed between 1911 and 1923 to add to the water supply. These dams were built decades before the U.S. Forest Service owned the area. In 1980, much of the land in the Rattlesnake Creek headwaters was designated as the Rattlesnake Wilderness and National Recreation Area. The existence and maintenance of the dams constitute a “special provision” in Wilderness. Maintenance can occur much as it had before the area was designated as Wilderness. Currently, the City of Missoula owns and is responsible for maintenance of these dams and many of the trails and roads which connect them. The City of Missoula and partner agencies are considering what to do with these dams, including repair and/or removal options.

After reading this paragraph, respondents were asked: “For each statement, please indicate your level of agreement: The dams should be…”

Data Collection

The study was approved by the University of Montana Institutional Review Board (Study #56-22) and Lolo National Forest. The visitor survey was administered at six trailhead locations providing access to the Rattlesnake Wilderness: the Main Rattlesnake, Equestrian, Sawmill Gulch, Lincoln Hills, Gold Creek, and West Gold Creek Trailheads (see Figure 3). The sampling locations were selected in collaboration with City of Missoula and US Forest Service personnel based on relative visitor traffic, access to varying portions of the Rattlesnake National Recreation Area and Wilderness, and previously conducted research (Watson et al. 1991; Williams et al. 1992). Sampling was randomly stratified by location, day of the week, and time of day, and occurred throughout the week, including weekends, from May 11, 2022, to February 19, 2023; surveys were administered in approximately eight-hour time-blocks, two days a week. A stratified-cluster sampling method was used to account for differences in the density of use among sites (e.g., the difference between weekday and weekend use) in an effort to conduct a representative survey at each access point (Vaske 2019).

Researchers utilized a random number generator and systematically intercepted visitors at the trailhead survey locations by approach- ing every nth person or group as they passed by to politely ask for their participation in the study. This number represented the minute on the hour for visitor interception. For example, if the number generated was an “8,” at 8 minutes past the hour the researcher would intercept the next visitor. For groups, one person over the age of 18 was asked to complete a survey. If multiple people were willing, then the person with the nearest birthday was selected to participate. If that person did not want to participate, another member of the group could volunteer if they desired. Survey responses were collected through the use of Qualtrics on tablets, or a paper copy of the questionnaire, if requested. Five surveys were completed through a QR code posted at the remote Gold Creek trailhead due to sparse use (less than one visit per day on average), and, in two instances, through a Qualtrics link sent via email, for visitors who could not complete the survey at the trailhead due to significant time constraints.

Data Cleaning and Analysis

Data cleaning and descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) are reported following guidance from Vaske (2019). “Straight-liners” (those answering each dam-related item with the same value, other than neutral) were removed from the dataset. Within-subjects ANOVA was employed to examine differences in respondents’ agreement between statements (Myers et al. 2010). In the case of non-sphericity, a Huynh-Feldt adjustment was applied (Myers et al. 2010). Statistical significance was assessed at a 99.9% confidence interval.

Results

With a response rate of 95.65%, a total of 398 responses were collected. The average age of respondents was 45 years old, with 77.3% of respondents residing in the greater Missoula, Montana, area. The majority of respondents identified as White (94.7%), followed by Asian (1.9%), American Indian or Alaska Native (1.4%), and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (0.2%).

As reported in Table 1, across our sample, the highest level of agreement among visitors was with the statement that the Rattlesnake Wilderness dams should be assessed on a case-by-case basis (M = 0.91), followed by agreement that the dams should be maintained and managed to provide climate resiliency (M = 0.65), and that they should be removed because they modify a naturally functioning ecosystem (M = 0.18). There was less agreement on the dams’ removal based on human development concerns and the dams’ maintenance for recreational amenities or historical and cultural significance. It is notable that, overall, the sentiments regarding the treatment of dams in wilderness are moderate, as no statements had a mean score exceeding an absolute value of 1 (i.e., all means were between -1 = Disagree and 1 = Agree on a scale ranging from -2 to 2). In other words, no means repre- sent strong agreement or disagreement (see Table 1). Standard deviations were relatively level across statement (ranging between 0.95 and 1.18).

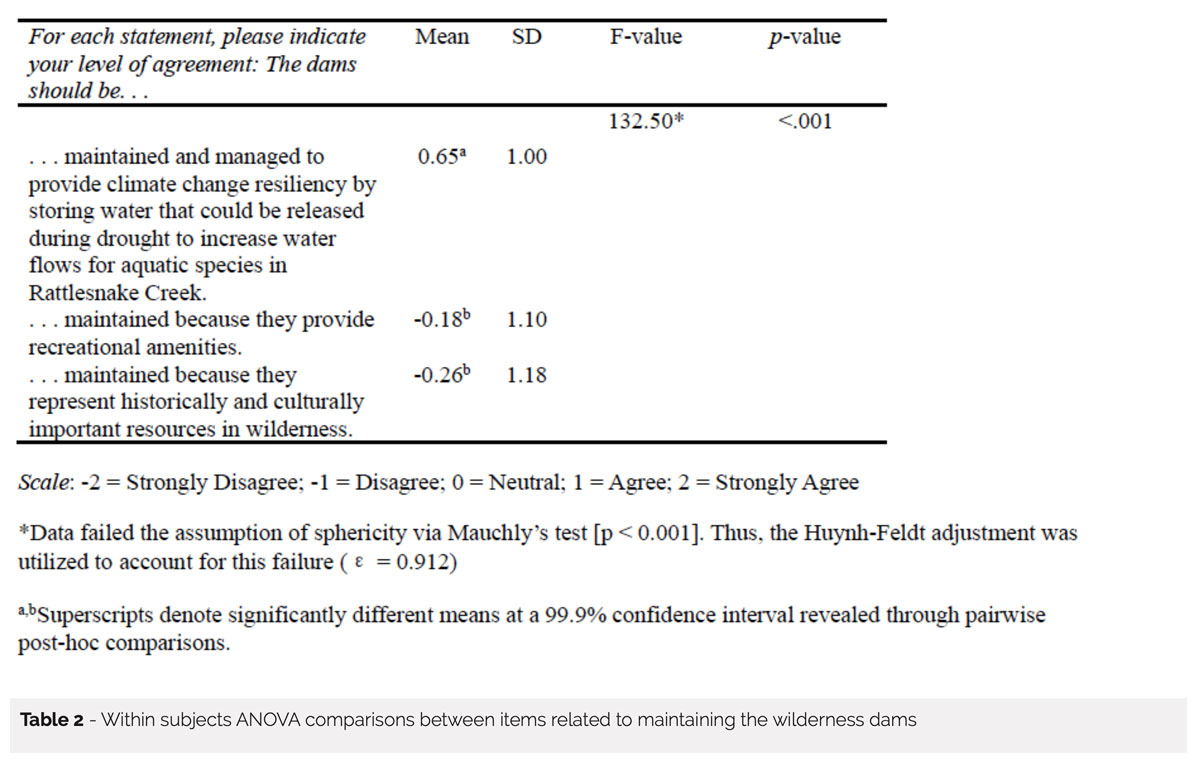

Table 2 presents the results of a within- subjects ANOVA examining individuals’ levels of agreement regarding the maintenance – not the removal – of the wilderness dams. The data violated a statistical assumption of sphericity. To address this, a Huynh-Feldt adjustment was applied. The first statement, with a mean of 0.65, suggests moderate agreement, on average, that the dams should be maintained and managed to provide climate change resiliency by storing water that can be released during drought to increase water flows for aquatic species in Rattlesnake Creek. The second and third statements, with means of -0.18 and -0.26, respectively, indicate relative disagreement to neutral feelings that the dams should be maintained for recreational amenities and as historically and culturally important resources in the wilderness. The ANOVA results reveal that participants are significantly more agreeable to maintaining the dams for climate resilience compared to other presented reasons.

Discussion

The findings of this study provide valuable insights into public attitudes toward the management of dams in wilderness areas, particularly in the context of wilderness character and climate change. Based on the results presented in Table 1, visitors appear to generally understand the complexity of the decision to remove or maintain the Rattle- snake Wilderness dams, as respondents, on average, agreed that the dams should be assessed on a case-by-case basis. It is also possible that engaged Missoula residents are aware that this is the current process for decision-making (Chaney 2021; Evans 2022). Importantly, this line of thinking also mirrors the national story of the dam dilemma in wilderness – with some being maintained, others being left to decay, and others being removed (National Park Service 2009; Nickas 1999; Zellmer 2012).

The moderate level of agreement regard- ing maintaining dams for climate change resiliency highlights the growing recognition of the challenges posed by climate change in wilderness management (Long and Biber 2014; Stephenson and Millar 2011). As climate change continues to impact ecosystems, the role of dams in storing and releasing water to support aquatic species during droughts becomes increasingly important (Evans 2022). This finding aligns with previous studies that have emphasized the flexibility of the Wilderness Act to adapt to the impacts of climate change (Nie and Barns 2012). It also suggests that visitors recognize the potential benefits (e.g., fishing opportunities, living in a more intact ecosystem, etc.) of maintaining these relatively small wilderness dams for ecosystem restoration and adaptation to changing environmental conditions in the northern Rocky Mountains.

The neutral to disagreeing sentiments reported, on average, regarding the maintenance of dams for recreational amenities and historical and cultural importance provide implications of their own. The lack of agreement concerning maintaining the dams for recreational value may be reflective of a number of factors, including the diverse recreational opportunities available across the Rattlesnake Wilderness (and the surrounding national recreation area) and the assumption that lakeside camping and fishing opportunities would still be available with smaller lakes (reduced back to their natural size once the dams were removed). Additionally, this finding may represent a disconnect between how visitors conceptualize the impacts of climate change on aquatic species and the recreational opportunities (i.e., fishing) that rely on those aquatic species. Concerning the lack of agreement on maintaining the dams for their historical and cultural importance, we reflect on the long-established trade-off between historic preservation and wilderness character (Carsley 2013; Chellis 2017; Stelson et al. 2020). It is entirely possible that the Rattlesnake Wilderness dams are eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places (Carsley 2013; Neuman and Reinburg 1989). If that were to occur, the goals of the National Historic Preservation Act and the Wilderness Act would need to be reconciled, as was deliber- ated by the courts in the Emigrant Wilderness (Carsley 2013). Our survey results provide a unique perspective concerning how visitors view this trade-off.

Differences in Agreement Regarding Reasoning for Maintaining the Dams

The results of the within-subjects ANOVA demonstrate that participants’ agreement levels differ significantly depending on the stated reasoning for maintaining the dams. Visitors showed significantly higher levels of agreement for maintaining dams for climate change resiliency compared to recreational amenities and historical/cultural significance. This suggests that the ecological rationale of maintaining dams for climate change adaptation resonates more strongly with visitors, indicating a recognition of the benefits of direct management in the face of environmental challenges. As shown in the Phillip Burton Wilderness example, such justification has been successfully used as a rationale – albeit to remove, not maintain – a wilderness dam (National Park Service 2009). However, it is important to ensure that such results – as those presented here – are not considered in a vacuum. The City of Missoula and US Forest Service, in the case of the Rattlesnake dams, likely will not base their decisions regarding the dams on a single reasoning. There is value in considering the contributions of each reason for maintaining or removing each dam, and the interactions between the underlying values behind each reason (e.g., how the climate resiliency provided by the dams would impact the recreation experience, how removing the development represented by the dams in wilderness would impact the recreation experience). Such complex reasoning mirrors the complexity of wilderness character. While the Keeping It Wild framework (Landres et al. 2008) places wilderness character qualities into the “bins” of undeveloped, untrammeled solitude or primitive and unconfined recreation, and the miscellaneous fifth quality – we stress that this reductionist approach may lead to overlooking the interactions between these qualities and the intangible nature of wilderness. It is difficult to hypothesize how a wilderness visitor might react, for example, to a bull trout’s rise to feed on a fly in Rattle- snake Creek – knowing that the bull trout’s very existence in this watershed is aided by developments in wilderness. Do the dams add or detract from the sense of wilderness? A quick wilderness character assessment might suggest that the dams’ presence in wilderness simply constitutes development and thus detracts. But, as our results suggest, it is not quite that simple.

Overall, these findings contribute to the ongoing discussion on the management of dams in wilderness areas. They highlight the importance of considering the unique circumstances and justifications for maintaining or removing dams on a case-by-case basis. Moreover, the results underscore the value of adaptive management strategies that consider climate change resiliency while carefully considering the impacts on wilderness char- acter, recreational opportunities, and cultural resources. The findings of this study present unique implications for wilderness managers and policymakers involved in dam manage- ment decisions. The recognition of visitors’ support for assessing dams on a case-by-case basis can inform decision-making processes by considering a range of factors, including ecological restoration, climate change adaptation, and cultural and historical significance. This study also emphasizes the importance of engaging with the public and incorporating diverse perspectives to ensure transparency and legitimacy in dam management decisions.

It is important to acknowledge, however, the limitations of this study. The research was conducted in a specific geographic context, an urban-proximate federally designated wilderness containing dams owned by a municipality, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other wilderness areas. Additionally, we did not ask participants to consider the rationale of maintaining or removing dams within the context of municipal uses, and other uses such as irrigation for agriculture and public safety, because such uses of dams are nominal in the Rattlesnake. However, municipal use, agricultural use, and/or public safety may be highly relevant in other contexts; indeed, managers of the Alpine Lakes Wilderness in Washington are currently challenged by a decision to allow dam construction (i.e., raise the height of an existing dam, maintain other dams) to, in large part, support downstream agricultural use and address safety concerns related to potential dam failure (Bush 2019). Third, we did not explicitly name bull trout in the questionnaire, instead referencing climate resiliency for aquatic species in general. It is possible that visitors’ perspectives may vary across aquatic species and their threatened or endangered status. Additionally, the inclusion of five surveys completed via QR code at a remote trailhead may introduce error into these results; however we elected to include these responses in an attempt to provide more complete, representative perspectives. Finally, the study focused on visitors’ perspectives, and further research is needed to explore the perspectives of other stakeholders, such as local communities, Indigenous groups, and environmental organizations.

Conclusion

This study provides valuable insights into visitors’ perspectives on the management of dams in federally designated wilderness. The findings demonstrate a nuanced perspective among visitors, with support for assessing dams on a case-by-case basis and recognizing the importance of managing wilderness for climate change resiliency. These results contribute to ongoing discussions on the management of wilderness areas in the face of climate change (Graber 2011; Long and Biber 2014; Stephenson and Millar 2011; Zellmer 2012) and highlight the need for adaptive management strategies that carefully balance ecological, recreational, and cultural considerations. Future research should continue to explore public attitudes and perspectives on dam management in different wilderness contexts to further inform decision-making processes and promote sustainable and resilient wilderness management practices.

WILLIAM L. RICE is an assistant professor of outdoor recreation and wildland management at the University of Montana, Parks, Tourism, and Recreation Management Program; email:william.rice@umontana.edu.

CHRISTOPHER A. ARMATAS is a research social scientist with the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute, USDA Forest Service; email: christopher.armatas@usda.gov.

References

Appel, P. A. 2015. Planning for adaptation and restoration in wilderness. George Washington Journal of Energy and Environmental Law 6(2): 52–59.

Bush, E. 2019, January 3. Officials seek dam upgrades in Alpine Lakes Wilderness to help salmon, water demand. The Seattle Times. https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/environment/officials-seek-dam-upgrades-in- alpine-lake-wilderness-to-help-salmon-water-demand/.

Camacho, A. E. 2010. Assisted migration: Redefining nature and natural resource law under climate change. Yale Journal on Regulation 27(2): 171–256.

Carsley, N. 2013. When old becomes new: Reconciling the commands of the Wilderness Act and the National His- toric Preservation Act. Washington Law Review 88: 525–558.

Chaney, R. 2021, August 24. Dammed if you do, damned if you don’t: Rattlesnake Wilderness presents challenges. Missoulian, 1.

Chellis, C. 2017. Playing nice in the sandbox: Making room for historic structures in Olympic National Park. Washing- ton Journal of Environmental Law & Policy 7(1): 35–64. https://doi.org/10.3868/s050-004-015-0003-8.

Evans, C. 2022, May 16. Could rehabbing dams in the Rattlesnake Wilderness help native trout struggling with cli- mate change? Montana Free Press. https://montanafreepress.org/2022/05/16/rehabbing-dams-in-rattlesnake- wilderness-may-help-native-trout/.

Galloway, B. T., C. C. Muhlfeld, C. S. Guy, C. C. Downs, and W. A. Fredenberg. 2016. A framework for assessing the feasibility of native fish conservation translocations: Applications to threatened bull trout. North American Journal of Fisheries Management 36(4): 754–768. https://doi.org/10.1080/02755947.2016.1146177.

Graber, D. 2011. Climate change threatens wilderness integrity. Park Science 28(3): 39–41.

Gunderson, K., and C. Cook. 2007. Wilderness, water, and quality of life in the Bitterroot Valley. In Science and Stew- ardship to Protect and Sustain Wilderness Values: Eighth World Wilderness Congress Symposium,: September 30–October 6, 2005, Anchorage, AK, ed. A. Watson, J. Sproull, and L. Dean (pp. 537–544). Proceedings RMRS-P-4. US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station.

Harvey, M. W. T. 1991. Echo Park, Glen Canyon, and the postwar wilderness movement. Pacific Historical Review 60(1): 43–67. https://doi.org/10.2307/3640418.

Landres, P., C. Barns, J. G. Dennis, T. Devine, P. Geissler, C. S. McCasland, L. Merigliano, J. Seastrand, and R. Swain. 2008. Keeping It Wild: An Interagency Strategy to Monitor Trends in Wilderness Character across the National Wilderness Preservation System. USDA Forest Service – General Technical Report RMRS-GTR. https://doi. org/10.2737/RMRS-GTR-212.

Long, E., and E. Biber. 2014. The Wilderness Act and climate change adaptation. Environmental Law 44: 623–694.

Myers, J. L., A. D. Well, J. R. F. Lorch, T. Woolley, S. Kimmins, R. Harrison, and P. Harrison. 2010. Research Design and Statistical Analysis, 3rd ed. Taylor & Francis Group.

Nash, R. 2014. Wilderness and the American Mind, 5th ed. Yale University Press.

National Park Service. 2009. Finding of No Significant Impact: Restoration of the Lower Glenbrook Quarry and Dam Removal at Turney Point. US Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Point Reyes National Seashore.

Neuman, L., and K. M. Reinburg. 1989. Cultural resources and wilderness: The white hats versus the white hats. Jour- nal of Forestry 87(10): 10–16.

Nickas, G. 1999. Preserving an enduring wilderness: Challenges and threats to the National Wilderness Preservation System. Denver University Law Review 76(2): 449–464.

Nie, M., and C. Barns. 2012. The fiftieth anniversary of the Wilderness Act: The next chapter in wilderness designation, politics, and management. Arizona Journal of Environmental Law & Policy 5: 236–300.

Proescholdt, K. 1985. Implementing environmental legislation: The Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness Act (P.L. 95-495). William Mitchell Environmental Law Journal 3: 1–42.

Stegner, W. 1955. The marks of human passage. In This Is Dinosaur: Echo Park Country and Its Magic Rivers, ed. W. Stegner (pp. 3–17). Alfred A. Knopf.

Stelson, L., W. L. Rice, and B. D. Taff. 2020. Managing cultural resources on the Alaska Peninsula. International Journal of Wilderness 26(2): 70–85. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7647625.

Stephenson, N. L., and C. I. Millar. 2011. Climate change: Wilderness’s greatest challenge. Park Science 28(3): 34–38.

Vaske, J. J. 2019. Survey Research and Analysis: Applications in Parks, Recreation and Human Dimensions, 2nd ed. Sagamore-Venture.

Watson, A., S. Martin, N. Christensen, G. Fauth, and D. Williams. 2015. The relationship between perceptions of wilder- ness character and attitudes toward management intervention to adapt biophysical resources to a changing climate and nature restoration at Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. Environmental Management 56(3): 653–663. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-015-0519-8.

Watson, A. E., D. R. Williams, and J. J. Daigle. 1991. Sources of conflict between hikers and mountain bikers in the Rattlesnake NRA. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration 9(3): 59–71.

Williams, D. R., M. E. Patterson, J. W. Roggenbuck, and A. E. Watson. 1992. Beyond the commodity meta- phor: Examining emotional and symbolic attachment to place. Leisure Sciences 14(1): 29–46. https://doi. org/10.1080/01490409209513155.

Zellmer, S. 2012. Wilderness, water, and climate change. Environmental Law 42: 313–374.

Read Next

Forgetting Your Anniversary, Again

This year represents the 30th anniversary of the International Journal of Wilderness.

The Trouble with Virtual Wilderness

How the history of the 20th-century wilderness movement might give us different moral guidance as we confront this new technology.

Revisiting Human’s Role in Wilderness

The question we must ask ourselves today is familiar: Are we guardians, or are we gardeners?