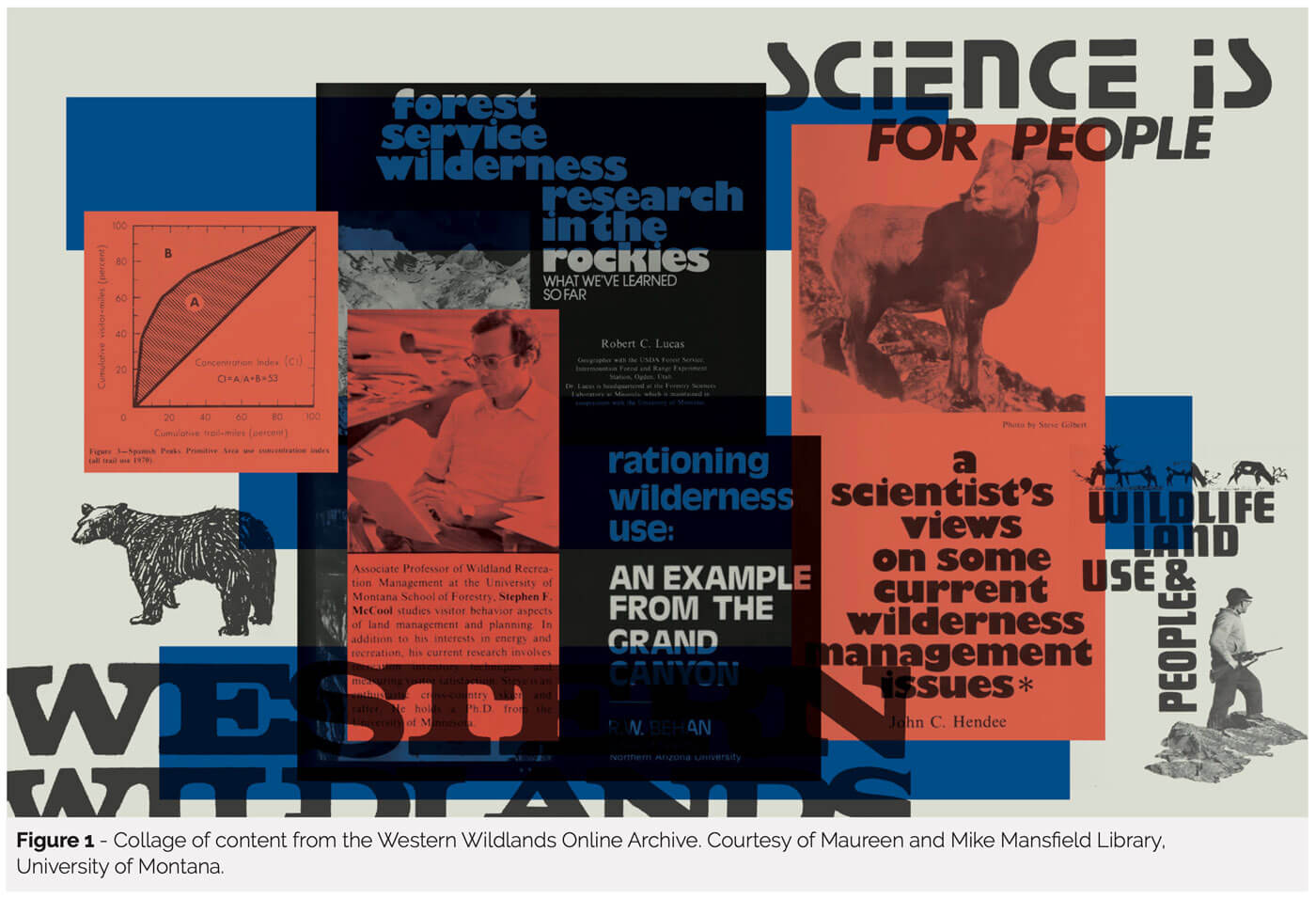

Photo credit: Selections from the Western Wildlands Online Archive. Courtesy of Maureen and Mike Mansfield Library, University of Montana. October 2024 | Volume 3

Introducing the Western Wildlands Digital Archive

BY WILL RICE

Communication + Education

October 2024 | Volume 30, Number 2

On a likely gray day in Washington, D.C., during the winter of 1974, a magazine-sized glossy publication found itself bouncing out of an incandescent mailroom on Capitol Hill, through a series of mailcarts, and eventually to the desk of US Senator Lee Metcalf. The nation was in the grips of the Watergate scandal and an oil shortage, but on one morning or late one evening that January, or perhaps February, the senator sat down to read the inaugural copy of Western Wildlands. In January 1974, the University of Montana’s Forest and Conservation Experiment Station minted its first issue of Western Wildlands – a publication remarkably like today’s International Journal of Wilderness – to “provide a service to the scientist, the resource manager, and the public by helping to bridge the communications gap.” We know Senator Metcalf read his copy that winter because he responded with a letter to the editor in the publication’s second issue in the spring of 1974 – commending the university for standing up the publication and the editors for striking a good balance between “practical” and “popular” articles.

From 1974 to 1992, a scrappy publication compiled quarterly in the Forestry Building at the University of Montana served as a key thoroughfare connecting wilderness research with management. Early wilderness recreation researchers published foundational science in a magazine format, written in an approachable style that sought to make implications clear to managers on the ground. Throughout the 1970s and ’80s, Dorothy Anderson, Bob Lucas, Steve McCool, Richard Schreyer, George Stankey, and other leaders in the field published in the pages of Western Wildlands what now provides the bedrock for applied wilderness research. In 1974, Bob Lucas provided a summation of wilderness research findings to date, stemming from the Rocky Mountains. In 1985, Joyce Kelly published a strong piece on “the need for a better understanding of, appreciation for and acceptance of” women in the wilderness profession and recognition women’s contributions in wilderness management. Many of the contributions related to wilderness recreation during Western Wildlands’ three-decade course focused on the conundrum of restricting and rationing wilderness visitation. This decades-long dialogue is a fascinating read for anyone who wrestles with the trade-offs of wilderness management – especially the trade-offs between solitude and confinement. The relevance of these articles today is remarkable. Reading George Stankey and Steve McCool’s 1991 article “Recreation Use Limits: The Wildland Manager’s Continuing Dilemma” in 2024 beckons the modern reader to reflect on how “the more things change, the more things stay the same.” In their article, Stankey and McCool provide a series of findings important for managers to consider prior to limiting use, including, among others, “recreation use level is often not the principal relevant variable that determines environmental impact” and “use limits represent value judgments about the acceptability of impacts.” In the same issue, Mary Beth Hennessy similarly wrestles with the struggle of balancing confinement in wilderness. In the publication’s final year of circulation, David Cole and Edwin Krumpe put forward “Seven Principles of Low-Impact Wilderness Recreation.” Written during the development of Leave No Trace outdoor ethics, this article serves ostensibly as a peek into the developers’ thinking during these early days.

For the previous three decades, this foundational work has been sequestered to dim library stacks at a few lucky western and midwestern university libraries in the US. Very few articles were available online. Those that were available were scattered across ResearchGate and various US Forest Service archives. The vast majority of this work had never been digitized, nor made available for the global wildland research and management community. Thus, in 2023, recognizing the need for unlocking this work, I partnered with Wendy Walker, professor and digital initiatives librarian, and Kelly Brown, digital collections and metadata specialist at the University of Montana’s Maureen and Mike Mansfield Library, and the University of Montana’s Forest and Conservation Experiment Station to digitize the Western Wildlands archive and make it globally available. The credit for making this dream a reality is truly owed to Wendy and Kelly, who did all the legwork in this venture. Today, readers can access the archive at https://scholar- works.umt.edu/westernwildlands/.

I’ve provided citations for a few of my favorites, below. Happy reading!

WILLIAM L. RICE is an assistant professor of Outdoor Recreation and Wildland Management at the University of Montana, Parks, Tourism, and Recreation Management Program; email:william.rice@umontana.edu.

Selected Citations

Bolle, A. W. 1991. Wilderness management: The new profession. Western Wildlands 17(2): 11–15. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/westernwildlands/66.

Cole, D. N., and E. E. Krumpe. 1992. Seven principles of low-impact wilderness recreation. Western Wildlands 18(1): 39–43. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/westernwildlands/69.

Hennessy, M. B. 1991. Limiting use in wilderness areas: Internal and external controls. Western Wildlands 16(4): 18–22. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/westernwildlands/64.

Jonkel, C. 1975. Of bears and people. Western Wildlands 2(1): 30–37. https://scholarworks.umt. edu/westernwildlands/5

Kelly, J. 1985. Women in wilderness management. Western Wildlands 10(4): 23–26. https://schol arworks.umt.edu/westernwildlands/40.

Lucas, R. C. 1983. The role of regulations in recreation management. Western Wildlands 9(2): 6–10. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/westernwildlands/34/.

Lucas, R. C., and S. F. McCool. 1988. Trends in wilderness recreational use: Causes and implications. Western Wildlands 14(3): 15–20. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/ westernwildlands/55.

Schreyer, R. 1977. Restricting recreational use of wildlands: Lessons from whitewater rivers. Western Wildlands 4(2): 45–52. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/westernwildlands/14.

Stankey, G. H., and S. F. McCool. 1991. Recreation use limits: The wildland manager’s continuing dilemma. Western Wildlands 16(4): 2–7. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/westernwild lands/64.

Read Next

Missing the Forest for the Algorithm

What is the value of wilderness? Well, what you have just completed reading is the “value of wilderness” as described by ChatGPT 3.5.

Rewilding Prerequisites: An Ecocentric Approach

Rewilding is increasingly gaining momentum as a conservation practice in Europe.

Trusting Tech and Wilderness in the 21st Century

A Response to Keeling’s The Trouble with Virtual Wilderness