Site of the Conservatoire du littoral dunes and forest of Porges, France, 2024. Photo by Thomas from Pixabay.

Wilderness Babel: When Ecological Meaning Fails to Express the Cultural Complexity of European Wilderness

BY ALEXANDRA LOCQUET and STÉPHANE HÉRITIER

International Perspectives

October 2024 | Volume 30, Number 2

Wilderness Babel is a project created by Marcus Hall, Wilko Graf Von Hardenberg, Tina Tin, and Robert Dvorak from the original online exhibit at the Environment and Society Portal of the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. It has been developed as an ongoing IJW series that discusses the terminology chosen to express wilderness as a concept in other languages or the nuances of this word in different English-speaking contexts. It discusses the adoption of the term “wilderness” in other cultural contexts – as well as other wilderness terms, from “outback” to “jungle,” and “bush” to “country.” And it explores how concepts of wilderness have found expression in visual representation in media of different sorts as well as in nonverbal communication.

A European Wilderness?

The wilderness concept has developed in the English-speaking world (Nash 2014). It has played a decisive role in American culture (Arnould and Glon 2006), contributing to a vast field of discussion and debate in the field of conservation (Callicott and Nelson 1998; Nelson and Callicott 2008). Indeed, wilderness is a highly ambivalent term, rather like a medal whose front has a cultural dimension (e.g., religion, ethical philosophy, and nature conservation) and whose back has an ecological and legal dimension (e.g., ecological dynamics, biodiversity, and the Wilderness Act of 1964 in the US). The different conceptualizations agree that the term “wilderness” commonly refers to wild areas where the influence or evidence of human presence is very slight, if not nonexistent. Intellectual movements and the creation of the first national parks helped spread the concept of wilderness around the world. However, this representation of nature is particularly problematic in countries where it has been used to support social exclusion and territorial dispossession of pre-European peoples during colonial times (Cronon 1996; Spence 2000).

In the European context, apart from the British Isles, the wilderness concept was not used to structure the actions of public stakeholders or national organizations until the 1990s. European languages reflect cultural sensitivities rooted in a history of relationships between human societies, their environment, and other species that inhabit it. Europe is the bearer of a range of imaginations and relationships to nature based on a triple heritage: first, the pre-Christian heritage that structured the relationships to the living space of the Germans, Scandinavians, Latins, Celts and Gauls, etc.; second, the agrarian heritage that shaped the relationship between nature and society; and third, the religious heritage, mainly Christian, which translates into distinct sensitivities in terms of relationships with the environment and with nonhuman beings.

At the European Union level, Natura 2000 has enabled the creation of a European nature protection network. It was set up within the framework of the Birds (1979) and Habitats (1992) Directives and aims to ensure the conservation of threatened species and habitats (Evans 2012). However, the concept of wilderness – or references to it – appeared later as a public policy tool. It emerged as a unifying concept for initiatives between European conservation practitioners in the 2000s (Bastmeijer 2016). It was imported into the debate under the influence of several organizations, such as Wild Europe, which is an NGO created in 2005. Comprising several nongovernmental and government-funded organizations (Pan Parks, UNESCO, Europarc Federation, World Wildlife Fund – WWF, IUCN), Wild Europe promotes and encourages strategies for the protection and restoration of wilderness areas in Europe (see Martin et al. 2002; Wild Europe 2013). And along with about a hundred organizations with varied interests (wildlife protection, environmental protection, tourism, government), it actively participated in promoting the concept to the European Parliament in 2008, culminating in the signing of the Wilderness in Europe Resolution (Resolution 2008/2210(INI)) voted on February 3, 2009 (Kun 2013). This resolution encourages member states to take action to identify and protect wilderness areas in their territories, using the existing protected areas within the European Natura 2000 network.

However, in the context of a European Union characterized by great cultural and ecological diversity, a question arises: Is there a common understanding of what European wilderness represents?

Semantic Limits when Translating a Polysemous Idea

The concept of wilderness is deeply rooted in cultural history, and a variety of connotations coexist even within the English-speaking world (e.g., biblical desert, transcendentalist conception, ecological conception). This highlights the difficulty of transposing and translating the term into other sociocultural contexts, especially in Europe where relationships with nature and the wild world are different within and between countries. With the exception of the Scandinavian languages, there are no exact translations of the word “wilderness” in most European languages (Washington 2007; Callicott 2008). The etymology of “wild-” comes from Teutonic and Nordic languages (Nash 2014). The German word wildniss is close to wildness and wilderness (Trommer 2021). Etymologically, wildniss is related to wald (forest) and wüste (desert, wasteland) In Dutch, wilderness is associated with wildernis (an area difficult to access) and woestenij (a wild area) (Stikvoort 2020). The “wild-” prefix is also found in the Swedish word vildmark, which designates an uncultivated, uninhabited wilderness (Elenius 2020). When the word is related to the forest environment, it refers to a virgin forest, a desolate and repulsive place. In Finnish, the word erämaa designates areas that cannot be penetrated by foot in less than one or two days, and where natural resources are available (Myllyntaus 2001).

In Latin languages, on the other hand, the translation of the term “wilderness” is trickier. For Barragan Paladines (2019), in Spanish, there is no common noun that can be used as an appropriate descriptor of wilderness; wilderness is described using only adjectives: salvaje (wild), silvestre (wild), inhóspito (inhospitable), prístino (pristine), intocado (untouched). The same applies to Italian, as Piccioni (2020) points out: “the best-known English–Italian dictionaries offer four possibilities: a) deserto, landa (desert), b) solitudine (solitude), c) riserva naturale (natural reserve), d) zona naturale incontaminata (incolta o disabitata) (natural uncontaminated area (unmanaged or uninhabited)).” In French, main syntagmas are based on the wild dimension and the absence of human interference. However, they do not satisfactorily express the cultural concept of wilderness (Locquet and Héritier 2020). Thus, the expressions nature sauvage or nature vierge (wild nature or virgin nature) are the most commonly used (Barthod 2010), while the term naturalité (as in the English term naturalness) is also used as a translation of wilderness by some authors (Lecomte 1999; Vallauri et al. 2010; Guetté et al. 2018).

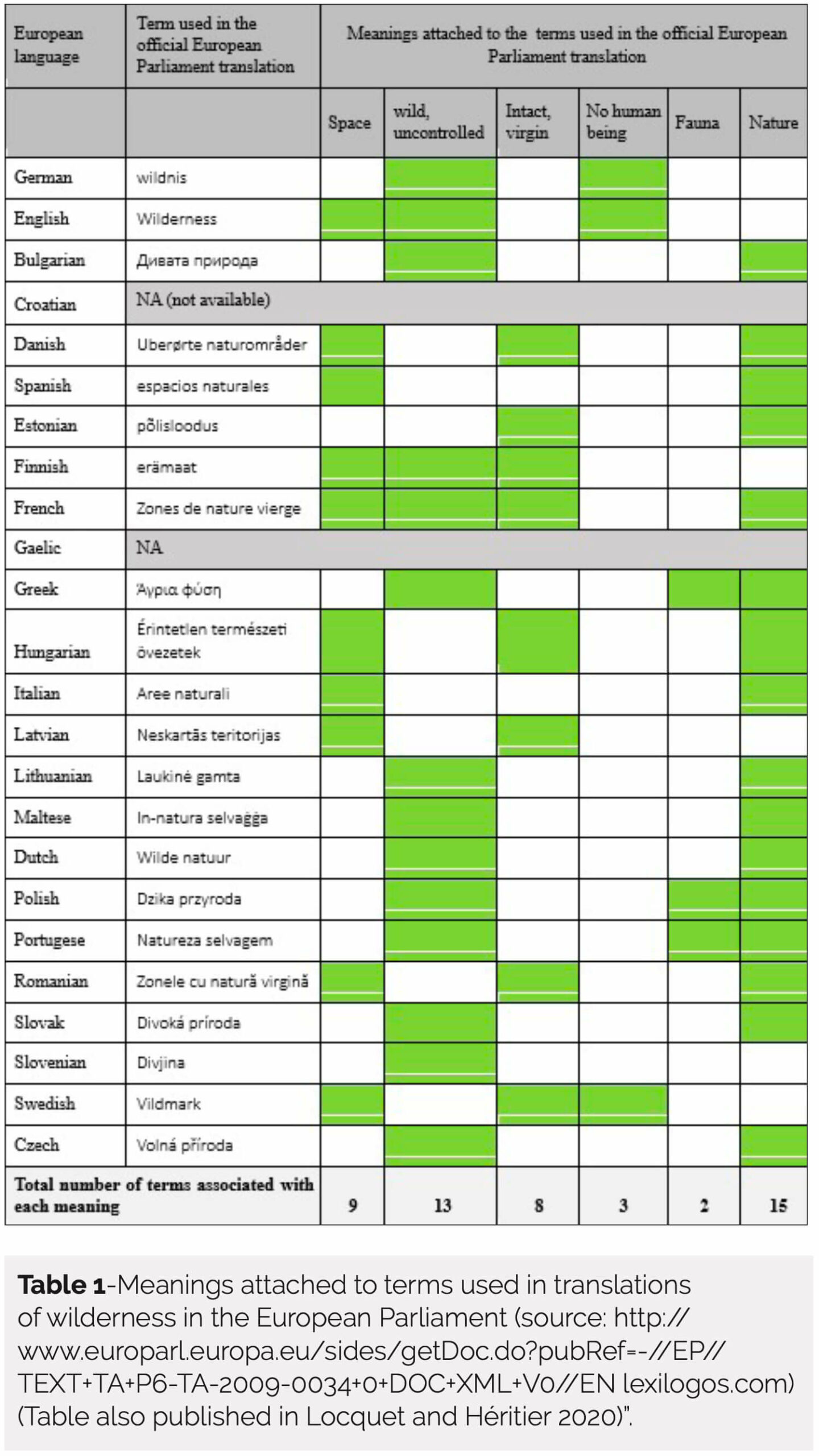

The international lingua franca of conservation uses the term “wilderness”. Yet translating it to fit the European cultural imaginary remains a challenge. The list of words used by European Parliament translators to identify appropriate equivalents for the English word wilderness reveals the challenge (Table 1) (Locquet and Héritier 2020). The complexity shows the difficulty of sharing an unambiguous generic term. This situation partly explains why the ecological conception of wilderness, refocused on naturalness; that is, on ecological criteria, now serves as a common referent. But this common ecological-scientific referent creates dissonance when it comes to inscribing it in local territories. Indeed, solving the problem of translation in semantic space does not solve the problem of translation in political space. Most expressions refer to wild and nature (the terms “sauvage” and “nature” in French, for example) and/or emphasize the spatial dimension of wilderness (which is absent from the French terms). Some translations reduce wilderness to an intrinsic state of nature, whereas the very essence of this notion lies in the variety of its meanings.

Table 1 illustrates the difficulty in translating the concept of wilderness. In methodological terms, this table compiled data from the official February 2009 resolution translations (available on the Parliament’s website; see URL in table source). The second column indicates the terms chosen by official interpreters to represent the notion of wilderness in different languages. For each language, we use the definition of the term chosen by interpreters to identify key notions that the interpreters had used to translate or transpose the word “wilderness.” The terms chosen by official translators may have a broader cultural meaning than the strict translation but are not included in this table.

Wilderness in a Context of Human-Made Environments

Nature and the environment have been both appropriated and culturalized in different ways. The United States passed a federal law in 1964 (Wilderness Act). Europe does not have a homogeneous legislative framework yet, although the European Union is working on it. It is well-known that human activities have long shaped European landscapes. Some of the landscapes that have been intensively modified by human activities are now being replaced by areas of agricultural abandonment, forest regrowth, and land abandonment. Thus, many European translations of “wilderness” refer to areas considered semi-natural or are characterized by a progressive degree of naturalness. For example, in Dutch, in a particularly artificialized country, “the term wildernis is therefore used for areas that are not visibly and recently touched by people. Thus, a meadow can be called wildernis if it is devoid of signs from human intervention, even though meadows are not ‘natural’ to the Dutch landscape and therefore show past human activity” (Stikvoort 2020). In French, the expression nature férale (feral nature) revives an old disused Latin word. Generally associated with animals or plants that have escaped domestication and returned to a wild state, it describes the return of spontaneous processes following rural abandonment or dereliction of human activities (Schnitzler and Génot 2012). In the UK, wild land or wild areas are two major concepts (Fritz 2001; Boyle and Wheeler 2016). The UK acknowledges the history of human modification of environments, and they refer to moderate naturalness due to human activity (Fritz, Carver, and See 2000; Fritz 2001). In Scotland, in particular, wild lands are recognized as semi-natural spaces that are marked by human modification, but are difficult to access (McMorran, Price, and McVittie 2006).

Moreover, the duration, and above all the intensity, of human activity have modified the European environment. A consensus seems to lead to one key interpretation, that of the greater or lesser intensity of human modification. This concept translates into theorizing a continuum or gradient of wilderness (Carver 2014). It considers various degrees of naturalness, proposing a gradation ranging from wilderness (considered as an “ideal” state, untouched by human activities) to areas that are heavily impacted by human activity. The ways in which wilderness is understood are thus largely dependent on the socio-ecosystem, including wildlife mobilization (particularly for large herbivores, such as in rewilding strategies) to let ecosystems evolve freely (such as the concept of libre évolution or “free evolution” in France).

In the end, from an English-speaking perspective and due to a common language, the concept of wilderness refers to connotations that may be different but that are known to authors and a large part of the public. In the European context, linguistic variety also refers to the diversity of ways for naming wild areas and talking about wild lands. The difficulties in translating “wilderness” into different European languages appear relatively rarely in English-language scientific literature. This provides an important insight into the understanding of initiatives in favor of wilderness and highlight the limits of the transposition of the concept due to the diversity of sociocultural contexts.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Tina Tin for her assistance with proofreading and translation.

ALEXANDRA LOCQUET is a geographer and researcher associated with the Ladyss laboratory (CNRS, France). She studies how wilderness is protected in France and Europe; email: locquetalex@gmail.com.

STÉPHANE HÉRITIER is a professor of geography in the Institute of Urban Planning and Alpine Geography and a member of PACTE research lab at Grenoble Alpes University (France); email: stephane.heritier@univ-grenoble-alpes.fr.

References

Barragan Paladines, M.-J. 2019. Wilderness as an adjective – Latin American Spanish | Environment & Society Portal.

Barthod, C. 2010. Le retour du débat sur la wilderness. Revue Forestière Française 62(1): 57–70. Bastmeijer, K. 2016. Wilderness Protection in Europe: The Role of International European and National Law. Cambridge University Press.

Boyle, S., and N. Wheeler. 2016. Wilderness protection in the United Kingdom. In Wilderness Protection in Europe: The Role of International European and National Law, ed. K. Bastmeijer. Cambridge University Press.

Callicott, J. B. 2008. Contemporary criticisms of the received wilderness idea. In The Wilderness Debate Rages on: Continuing the Great New Wilderness Debate (pp. 355–377), ed. M. P. Nelson and J. B. Callicott. University of Georgia Press.

Callicott, J. B., and M. P. Nelson. 1998. The Great New Wilderness Debate. University of Georgia Press.

Carver, S. 2014. Making real space for nature: A continuum approach to UK conservation. Ecos 35(3/4): 4–14.

Cronon, W. 1996. The trouble with wilderness: Or, getting back to the wrong nature. Environmental History 1(1): 7–28.

Elenius, L. 2020. Vildmark and ödemark – Swedish. Environment & Society Portal. 2020.

Evans, D. 2012. Building the European Union’s Natura 2000 network. Nature Conservation 1: 11–26.

Fritz, J. M. 2001. Mapping and modelling of wild land areas in Europe and Great Britain: A multi-scale approach. School of Geography, University of Leeds.

Fritz, S., S. Carver, and L. See. 2000. New GIS Approaches to Wild Land Mapping in Europe. USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-15, 2: 120–127.

Guetté, A., J. Carruthers-Jones, L. Godet, and M. Robin. 2018. « Naturalité » Concepts and methods applied to nature conservation. CyberGeo 2018: 1–25.

Kun, Z. 2013. Preservation of wilderness areas in Europe. European Journal of Environmental Sciences 3(1): 54–56.

Lecomte, J. 1999. Réflexions sur la naturalité. Le Courrier de L’environnement de l’INRA 37: 5–10.

Locquet, A., and S. Héritier. 2020. Questioning nature and wildness in relation to the establishment of wilderness areas in Europe. CyberGeo: European Journal of Geography.

Martin V. G. et al. 2002. Wilderness momentum in Europe. International Journal of Wilderness 14(2): 34–38, 43. 64 International Journal of Wilderness | October 2024 | Volume 30, Number 2

McMorran, R., M. F. Price, and A. McVittie. 2006. A Review of the Benefits and Opportunities Attributed to Scotland’s Landscapes of Wild Character. Commissioned Report No. 194 (ROAME No. F04NC18). Scottish Natural Heritage.

Myllyntaus, T. 2001. Encountering the Past in Nature: Essays in Environmental History. Ohio University Press.

Nash, R. 2014. Wilderness and the American Mind. Yale University Press.

Nelson, M. P., and J. B. Callicott. 2008. The Wilderness Debate Rages on: Continuing the Great New Wilderness Debate. University of Georgia Press.

Piccioni, L. 2020. A language without wilderness – Italian. Environment & Society Portal.

Schnitzler, A., and J.-C. Génot. 2012. La France Des Friches : De La Ruralité à La Féralité. Quae.

Spence, M. D. 2000. Dispossessing the Wilderness: Indian Removal and the Making of the National Parks. Oxford University Press.

Stikvoort, B. 2020. Wildernis and woestenij – Dutch. Environment & Society Portal.

Trommer, G. 2021. Wildnis/wildness/wilderness – Erfahrung und bildung. In Naturerfahrung Und Bildung, ed. A. Möller et al.

Vallauri, D., J. André, J.-C. Génot, and R. Eynard-Machet. 2010. Biodiversité, Naturalité, Humanité Pour Inspirer La Gestion Des Forêts. Lavoisier.

Washington, H. G. 2007. The “Wilderness Knot.” In Proceedings RMRS-P-49. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. (pp. 441–446), ed. A. Watson, J. Sproull, and L. Dean, 049. Anchorage, AK.

Wild Europe. 2013. A Working Definition of European Wilderness and Wild Areas.

Read Next

Missing the Forest for the Algorithm

What is the value of wilderness? Well, what you have just completed reading is the “value of wilderness” as described by ChatGPT 3.5.

Rewilding Prerequisites: An Ecocentric Approach

Rewilding is increasingly gaining momentum as a conservation practice in Europe.

Trusting Tech and Wilderness in the 21st Century

A Response to Keeling’s The Trouble with Virtual Wilderness