Here, scenes of Ghost Ranch on the edge of the Carson National Forest on the Rio Chama Landscape. Photo credit: USDA Forest Service photo by Preston Keres

The Power of Invitation: Wilderness Managers as Collaborative Hosts

by TANGY EKASI-OTU

Communication + Education

April 2024 | Volume 30, Number 1

Managers of Land and Relationships

Federal wilderness managers play a unique role in the world of conservation and stewardship. Not only are they tasked with maintaining characteristics of wilderness – for example opportunities for solitude – but they are also tasked with tailoring their management approach to the unique communities and lands they serve. Since its passage, the Wilderness Act of 1964 has referenced the important role that education and service to the public play in administering the National Wilderness Preservation System “for the permanent good of the whole people.” Rising visitation numbers and changes in society’s connection to the outdoors have added additional emphasis to this call to educate and engage the public with wilderness. In recent decades, this need has been formalized into mandates, executive orders, and agency policy in the form of direction to serve communities and address the dissonance and inequality in access and experiences of visitors.

Given the numerous mandates and directives, many wilderness managers have taken up opportunities to engage in roundtable discussions, conferences, training, and other means to get a better picture of how they can serve a diverse audience. However, barriers to advancing this work remain, and the way federal wilderness manager roles are supported and perceived heavily impacts their relationships with the public.

Federal land management agencies employ a relatively small number of individuals to monitor and maintain wilderness areas. Of these individuals, an even smaller number have supported roles that focus on community engagement, while some wilderness areas have no specific person focusing on this at all. Furthermore, the role of wilderness manager has largely been expected to focus on the landscape, with an emphasis on tradi- tional skills such as the use of saws or other nonmechanical tools to maintain the character of the wilderness. These skills are a part of the unique heritage of wilderness, and there is room to leverage these activities, combine them with better support and resources, and shift some focus to community engagement through wilderness education and culture building. Community engagement has often been an ad-hoc duty, championed by individuals who go above and beyond to add it to their workload. As a result, community engagement has often been peripheral to the central duties and roles of wilderness manag- ers, in contrast to the vision reflected in the full missions of the Wilderness Act.

The purpose of this article is to examine how wilderness managers can address diverse needs and perspectives by building culture through education and outreach. By moving beyond traditional education techniques to be collaborative hosts, wilderness managers can leverage their skill sets and platforms to improve society’s connection to wilderness.

Wilderness Managers Address Diverse Needs and Perspectives

Executive Order 13985, Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government, requires the head of each agency to prepare a plan for addressing any barriers to full and equal participation in programs, services, procurement, contracting, and other funding opportunities. Other administration and land management agency priorities include but are not limited to: the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act; the Confronting the Wildfire Crisis implementation strategy; the American Rescue Plan Act; the America the Beautiful initiative; the Great American Outdoors Act; the Justice40 Initiative; the Climate Conservation Corps; the Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility strategy; and the Climate Adaptation Plan.

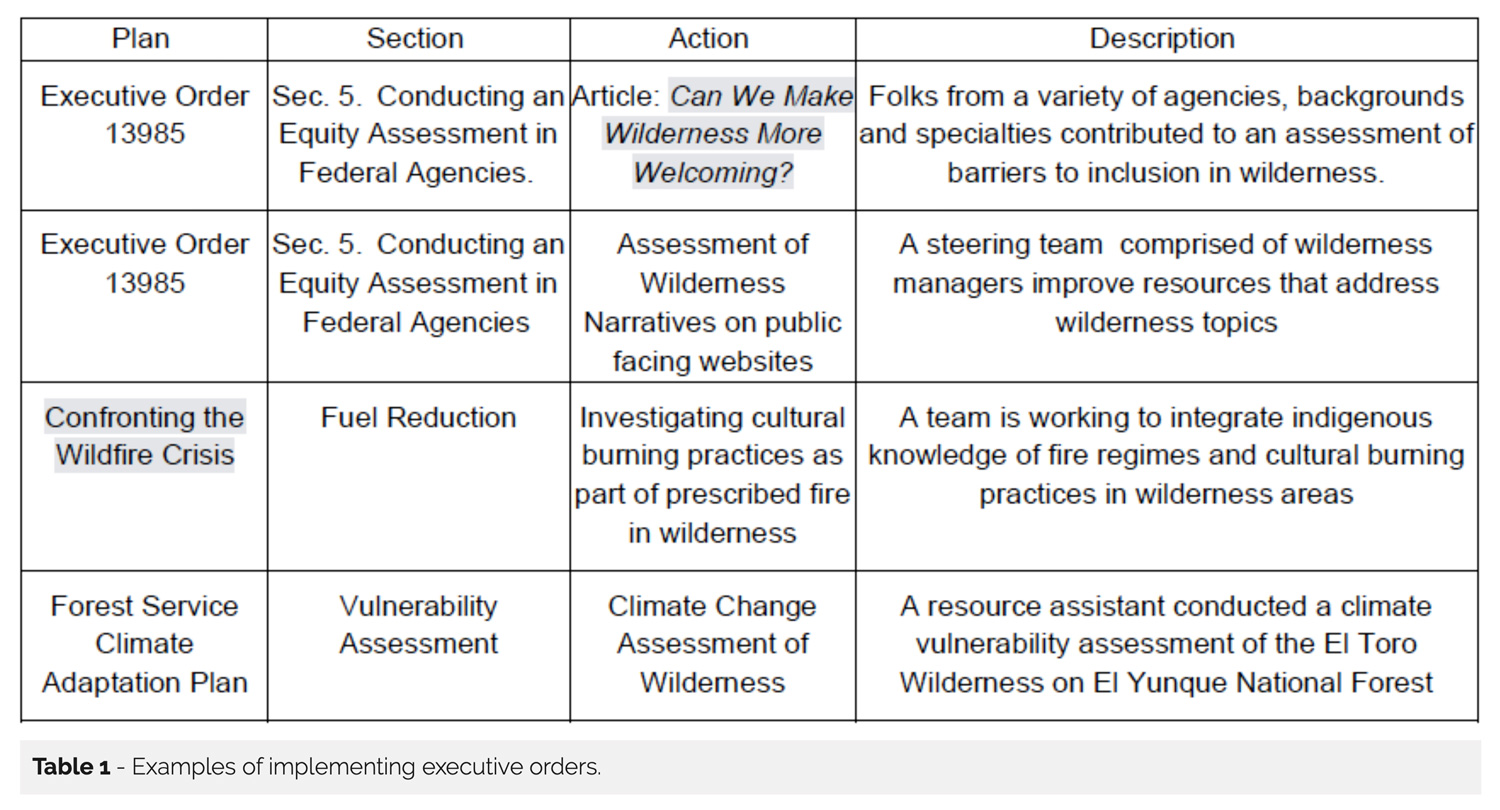

Many of these plans and strategies are not only calling on federal agencies to serve the public by providing opportunities and facilities but also to take an intentional approach to engaging underserved communities. There is much to uncover in understanding what it takes to reach the “whole people” in this way. There are cultural gaps between land managing agencies and communities that leave their values, histories, priorities, and connections to the land unaddressed. Extending an invitation to visit wilderness lands is part of closing this gap, but an invitation to participate in and shape wilderness culture is what can lead to lasting, meaningful experiences in wilderness (Table 1).

Tracy Brower (2020) speaks to this concept of community and culture building, saying, “Strong communities have a significant sense of purpose. People’s roles have meaning in the bigger picture of the community and each member of the group understands how their work connects to others’ and adds value to the whole. As members of community, people don’t just want to lay bricks, they want to build a cathedral.” So how can wilderness educators and managers focus on community and cul- ture building? How do wilderness education approaches typically address outreach and communication?

Education and Outreach for Culture Building with Underserved Communities

When wilderness education is approached in the traditional format where the federal manager is the “teacher” and the visitor is the “student,” many limitations and issues can arise. In this model, the information shared is inherently limited by what one individual can learn and communicate. Even the most learned interpreter who seeks to recall a diversity of stories, viewpoints, values, and histories associated with a wilderness area can only begin to scratch the surface. Additionally, their ability to communicate that information in an impactful way is limited by many factors outside of their control, such as time, resources, and perceptions of the visitors. This is why working as individual interpreters falls short of the goal of serving all communities with meaningful experiences on wilderness lands.

Teaching and interpreting should not be done away with, but they can instead be leveraged as part of a wider effort to build up a wilderness community that has a distinct culture shaped by both visitors and managers. By being community focused, a wilderness manager can maximize their impact across a network of people and get to the heart of inclusivity. This means that the role of managers would shift from that of individual teachers to collaborative hosts.

Collaborative Hosts Provide Meaningful Experiences on Wilderness Lands

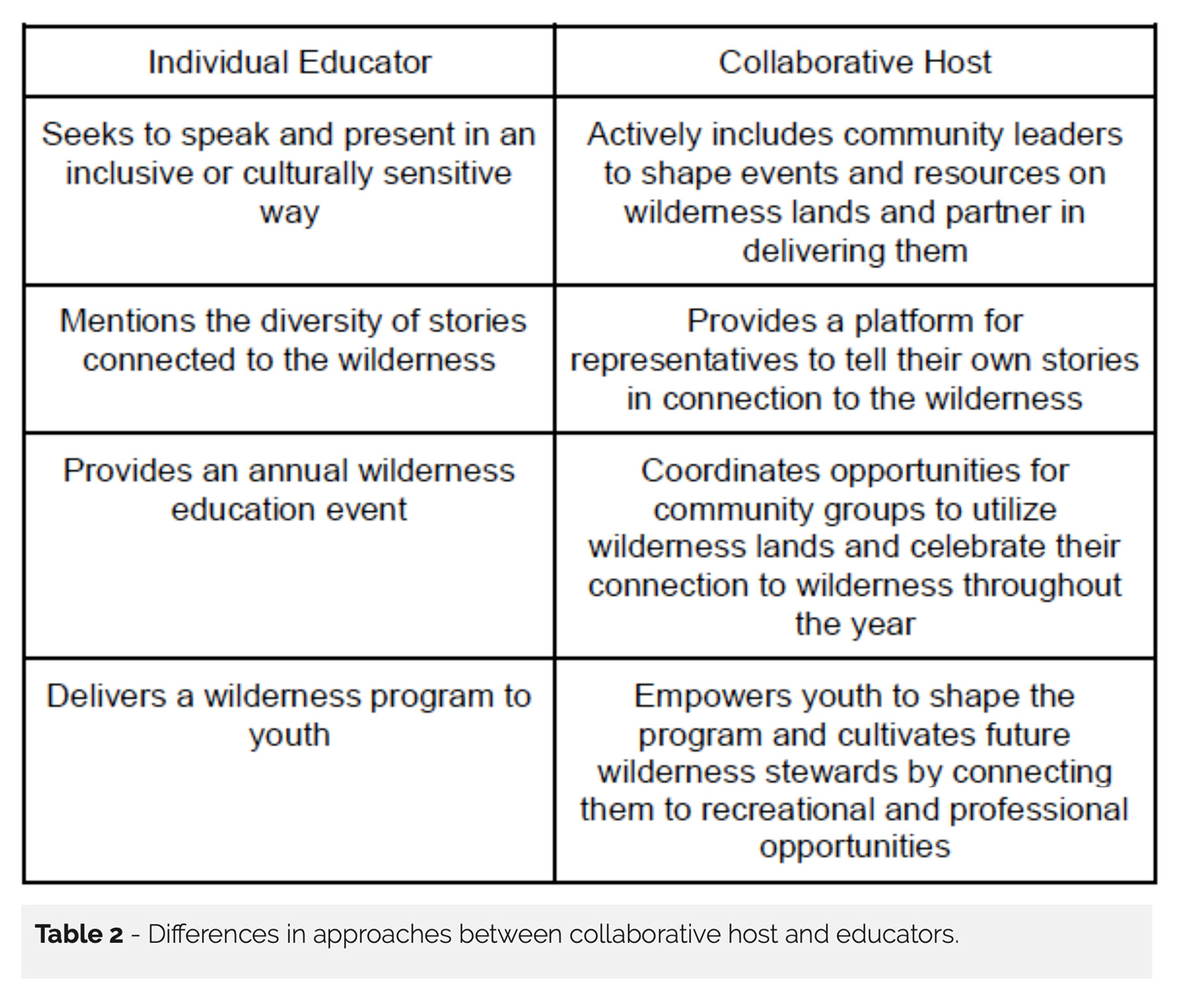

The benefits of working as a collaborative host include empowerment of communities and maximizing the impact of community engagement. While traditional methods of wilderness education may have similar goals, there are key differences in the mindset of a “host” versus an “educator” (see Table 2).

Federal wilderness managers can make excellent hosts because they can provide key insight into the conditions of wilderness areas; leverage agency resources; authorize uses and permits; teach about traditional wilderness skills such as crosscut saw use, packing, and Leave No Trace principles; and share their passion for the places they help steward. Some managers also have unique strengths such as personal relationships, bilingual skills, specialized knowledge, and partnership experience. By understanding the unique platform that federal managers have, along with their skill set, they can be better supported in their outreach and community-building efforts by their respective agencies and by one another.

To be collaborative, wilderness managers can take an inventory of community leaders. Some leaders may have a direct and long- standing connection to the wilderness, such as native nations, adjacent landowners, or frequent visitors. Other leaders may not have been engaged with the wilderness, but they do have shared values concerning the benefits of wilderness, such as youth organizations, the art community, historical societies, universities, health-focused organizations, and a multitude of recreationists.

If it’s difficult to identify a diversity of leaders interested in engaging with wilderness, this may indicate that there is a need to cultivate new leaders and help identify connections to wilderness in different cultural contexts. Giving agency to the experiences of new visitors, and highlighting their intersecting knowledge is a part of that process, along with reaching out into the community in nontraditional venues where leadership exists but may need more connection to wilderness.

Overall, by building relationships with other community leaders and cultivating new ones, a sense of community around the wilderness begins to emerge. Community is the best venue to showcase the character of wilderness and share values and information because it can be shared over a foundation of trust and relationships. Collectively, a community that shares the stage and passes the microphone is best able to represent the depth and diversity within it.

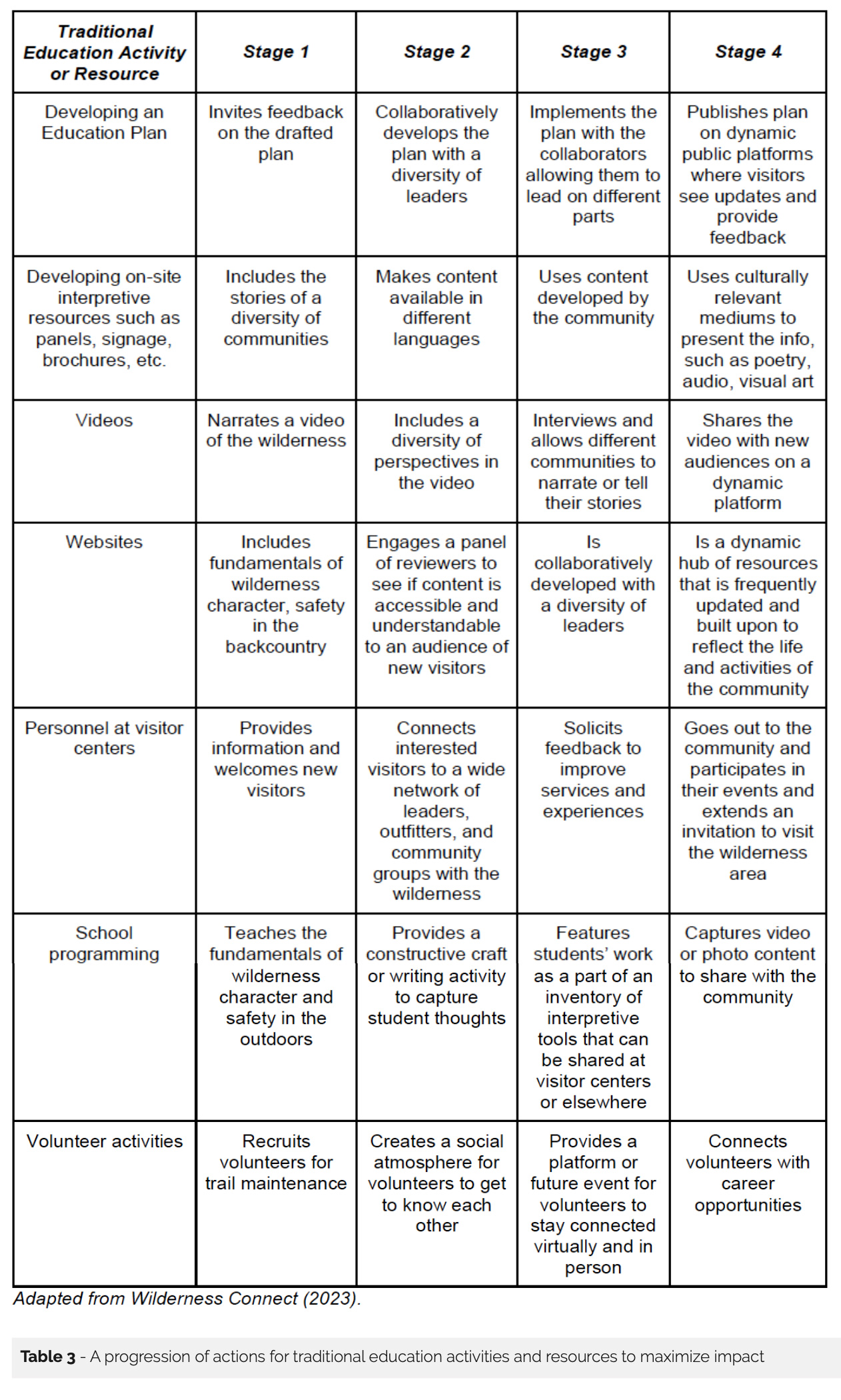

Taking a collaborative mindset to traditional education activities can result in a progression of thinking that maximizes impact (see Table 3).

Networking with Collaborative Leaders to Maximize Impact

There are many leaders already employing some of these mindsets in the wider outdoor community. Amy Dominguez and Olivia Juarez are two community leaders who have taken initiative in wilderness education by hosting the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance’s Utah Silvestre podcast (see Patrick Kelly’s review in the June 2023 issue of IJW). The miniseries is available in both in Español and English and is dedicated to recognizing that the Redrock Wilderness is embedded in the community’s wellness, cultural histories, traditions, and future. They have created a dynamic platform to share their community’s connection to these wilderness lands and contributed content that helps represent the wilderness. In the opening episode titled “Public Lands Explained,” an individual remarked, “I was only five hours away from these beautiful red rock places. I just never knew that as a young child but, intrinsic to me is just this understanding that public lands and land on which we exist, there’s no ownership of that, it is just . . . we have to care for it. There is that just strong feeling of stewardship that I was raised with as a very young child so that is my personal connection, it is ingrained in my DNA.”

The Southern Appalachian Wilderness Stewards (SAWS) also use a collaborative mindset in the management of wilderness areas in the Southeast where the number of federal land managers can be sparse. Federal managers who do hold wilderness-specific positions work closely with SAWS to leverage a wide network of thinkers and volunteers who not only provide technical assistance but have also built a unique culture and community around wilderness and are committed to diversifying it. Their willingness to engage other community leaders such as educators has led to some unique partnerships. For example, they recently hosted a Kenan fellow, from the North Carolina State program to get educators connected to STEM-related networks and encourage students to pursue STEM-related career fields. The fellow reflected on the project: “My project and fellowship is to develop lessons and resources to engage students, particularly underrepresented groups, in environmental stewardship and outdoor recreation. I am a history teacher, but I have a calling to get more students involved in the outdoors and connect with our wilderness areas” (see also Redmore et al. 2023).

All wilderness educators can benefit from connecting with networks of community leaders, working collaboratively and hosting spaces for a wilderness community to grow and thrive. This is a critical step in uncovering the true depth of history and connections to wilderness lands today that allow “the whole people” to not just visit wilderness, but to build a personal connection with it that leads to stewardship. For all the differences in individual connections to wilderness, stewardship is a central value of many cultures and a key sentiment behind the Wilderness Act itself. We will not get the full picture of the complexities of stewardship and connection to the land until everyone can share their expertise amongst a trusting and inclusive community.

TANGY EKASI-OTU is the wilderness and wild and scenic rivers specialist for the Forest Service’s Washington Office and former Hispanic Access Foundation fellow; email: tangy.ekasi-otu@usda.gov

References

Brower, T. 2020. How to build community and why it matters so much. Forbes. Retrieved on January 26,

2024 from https://www.forbes.com/sites/tracybrower/2020/10/25/how-to-build-community-and-why-it-mat- ters-so-much/?sh=45711c57751b.

Kelly, P. 2023. Digital Reviews. Utah Silvestre, hosted by Amy Dominguez and Oliva Juarez. International Journal of Wilderness 29(1): 104.

Redmore, L., K. Fox-Middleton, K.-H. Crum, M. Gregory, C. Motahari, M. Powers, R. S. Armendariz, A. G.

Santos, and L. S. von Haupt. 2023. Toward a toolbox for diversity, equity, and inclusion in wilderness: Findings from five focus group discussions with wilderness professionals. International Journal of Wilderness 29(2): 84–109.

Wilderness Connect. 2023. Wilderness education techniques. Retrieved on January 26, 2024, from https://winapps.umt.edu/winapps/media2/wilderness/toolboxes/documents/education/wild_ed_techniques. pdf.

Read Next

Forgetting Your Anniversary, Again

This year represents the 30th anniversary of the International Journal of Wilderness.

The Trouble with Virtual Wilderness

How the history of the 20th-century wilderness movement might give us different moral guidance as we confront this new technology.

Revisiting Human’s Role in Wilderness

The question we must ask ourselves today is familiar: Are we guardians, or are we gardeners?