Emerging and early career professionals exposed to wilderness management experiences. Photo credit: Ryan Leonard.

Introducing Emerging and Early Career Land Management Professionals to the National Wilderness Preservation System: Creating Opportunities across US Federal Recruitment Programs

by KIMM FOX-MIDDLETON

Stewardship

December 2023 | Volume 29, Number 2

“It is more important than ever to ensure continued wilderness stewardship, and a stewardship that reflects the changing demographics of our nation.”

A Retiring Workforce Opens Doors

The full title of the Wilderness Act, “To establish a National Wilderness Preservation System for the permanent good of the whole people, and for other purposes,” explains our responsibilities as wilderness managers to ensure that wilderness “shall be administered for the use and enjoyment of the American people in such manner as will leave them unimpaired for future use and enjoyment as wilderness” (Wilderness Act, Section 2a). Since 1964, the National Wilderness Preservation System has protected wild lands managed by the US Department of Interior and the US Department of Agriculture across the country, and currently is comprised of more than 111 million acres, spanning all 50 states and Puerto Rico. It can be challenging to manage wilderness given the diversity of sizes and locations, management agencies, and on-the-ground issues faced by managers. These challenges are compounded by environmental and social changes that are redefining how we manage wilderness, what we manage in wilderness, and why we manage wilderness; these changes also are impacting who manages wilderness.

Almost one-third of the federal workforce will soon be eligible for retirement, with many retirements happening in the coming months (Weisner 2022). This includes many wilderness managers who have decades of experience and are now, more urgently than ever, called upon to serve as coaches, mentors, and sponsors for emerging and early career professionals to ensure relevancy and sustainability of our nation’s wildernesses. Not only does the present work- force have a lot of knowledge, skills, and experience to share with emerging and early career workers, but emerging and early career workers have a lot to share with more experienced workers.

As a parent of two Generation Z daughters, I understand that the opportunities they have today shape their career choices and paths into the future. I value firsthand the opportunity to learn how my daughters apply their perspectives into the workforce, and I carry this into my wilder- ness work. Generation Z has grown up in the “digital age” and has ready access to an exorbitant amount of information. As a result, they may be considered the best-educated generation yet (Parker and Igielnik 2020). My daughters’ approach to work, like many in their generation, reflects this early exposure to knowledge. They are problem solvers, interested in collaborating across disciplines and contexts. They are also committed to causes that support a more equitable and sustainable future. These and other qualities influence how they and others in their generation enter the workforce and, in turn, the kinds of mentorship and opportunities they seek out.

Early work opportunities can shape long-term career trajectories, leading to higher recruitment and a more engaged and skilled workforce. Where funding opportunities are limited, for example in federally designated wilderness, we may struggle to recruit capable, qualified, and passionate individuals to steward our nation’s public lands. Without significant funding to attract talent, creative approaches are required to achieve the same goal. This article describes an effort to create opportunities for emerging and early career land management professionals to learn about, work in, and support wilderness management.

In my role as wilderness interpretation and outreach specialist at the Arthur Carhart National Wilderness Training Center (ACNWTC), I understand firsthand some of the challenges facing recruitment of the wilderness workforce. Other sectors of public land administration have successful recruitment efforts through various internships and professional pathways programs. Yet, I learned that very few of them were gaining exposure to the National Wilderness Preservation System. I wanted to ensure that my work was speaking not just to well-seasoned wilderness managers but also connected with newer generations of wilderness managers who may bring new ideas, perspectives, and experiences to their work.

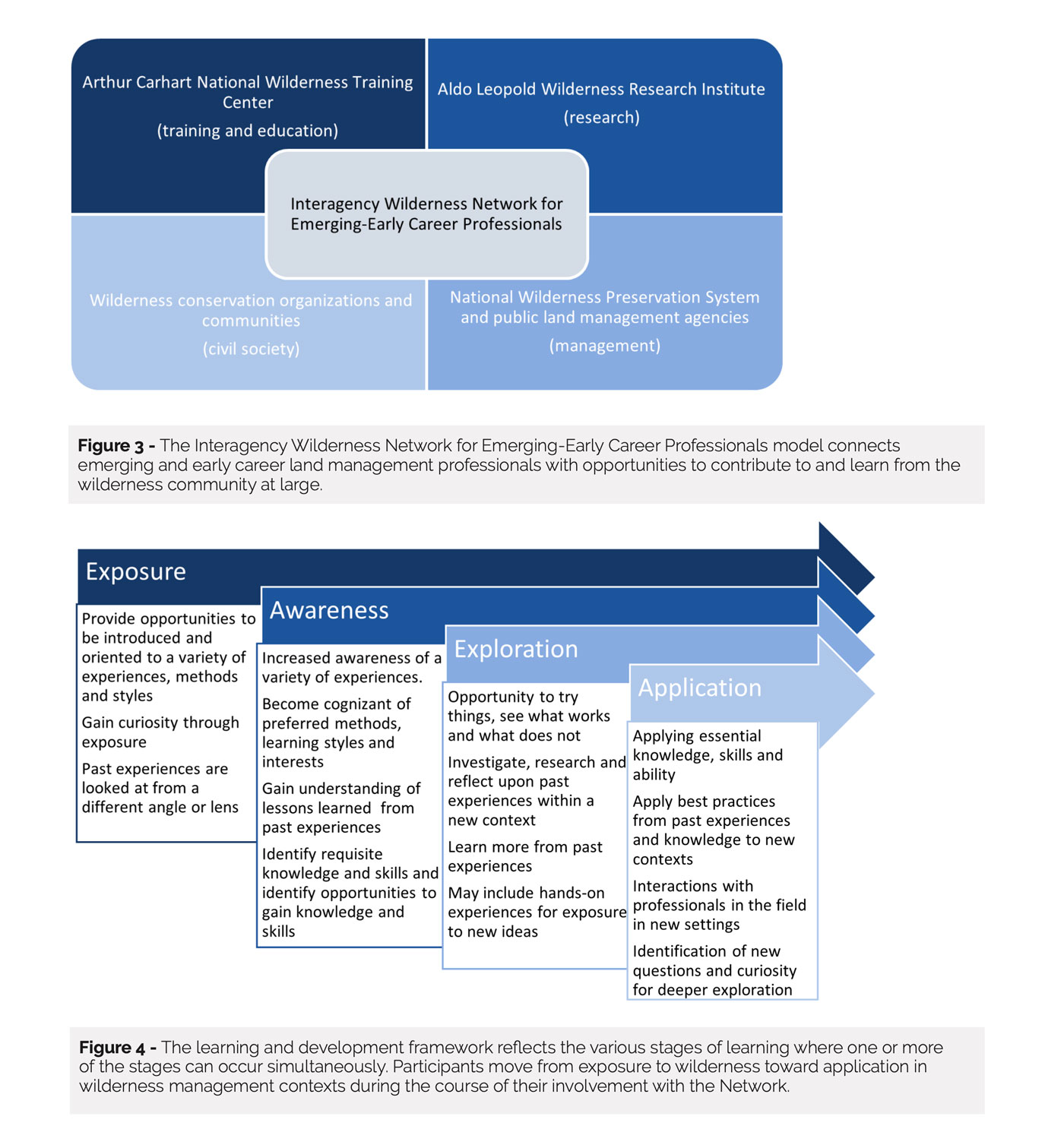

I reached out to connect with these emerging and early career land management profession- als to tap into their knowledge, experience, and enthusiasm, and have since worked many times with them. This led to my interest in forming an Interagency Wilderness Network for Emerging- Early Career Professionals (hereafter referred to as “the Network”). The purpose was to develop a network for land management emerging and early career professionals and to connect them with the work of ACNWTC and the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute (ALWRI). Today, the Network is a partnership that seeks to extend wilderness into the home unit, contribute to wilderness management, and share opportunities to learn more about diverse wilderness work (Figure 1). Specifically, the Network aims to:

- Increase the exposure of the National Wilderness Preservation System across land management agencies

- Build capacity for wilderness research, education, outreach, and stewardship for participants through training opportunities

- Raise awareness about ACNWTC and ALWRI and their missions to new and future permanent hires

- Incorporate perspectives of emerging and early career professionals in the development of wilderness education, research, stewardship, and training

- Reach beyond the traditional pool of agency staff to expand the impact of ACNWTC and ALWRI and ensure their continued relevance in an era of expanded partnership responsibilities and increasingly diverse workforce

Establishing the Interagency Wilderness Network for Emerging-Early Career Professionals

Starting in 2021, I worked with colleagues across agencies to identify needs in wilderness interpretation and outreach where emerging and early career professionals could add value. I first learned about the Forest Service Resource Assistant Program, many of whom were eager to gain more experience beyond their home unit and assigned work. As a result, early recruits to the Network were Forest Service Resource Assistants brought to the agency through partnership organizations such as the Hispanic Access Foundation. Recognizing this opportunity to improve the quality and reach of my work, I sought to identify similar opportunities to work with other agencies and their cohorts of emerging and early career professionals (Figure 2). I learned that many of these emerging and early career professionals were being exposed to management of federal lands but not necessarily to the management of the National Wilderness Preservation System. The goal for me was not only to learn from them and leverage their valued perspectives, knowledge, and skills but to provide them with opportunities to connect their work to wilderness management, training, and research.

Emerging and early career professionals are primarily supported by staff at the ACNWTC and ALWRI as opportunities arise. In the process of working with ACNWTC and ALWRI, they have opportunities to connect with and learn about the National Wilderness Preservation System, the multiple agencies that manage wilderness, and the organizations that advocate, volunteer for, and support wilderness stewardship more generally.

The Learning and Development Framework That Guides the Network

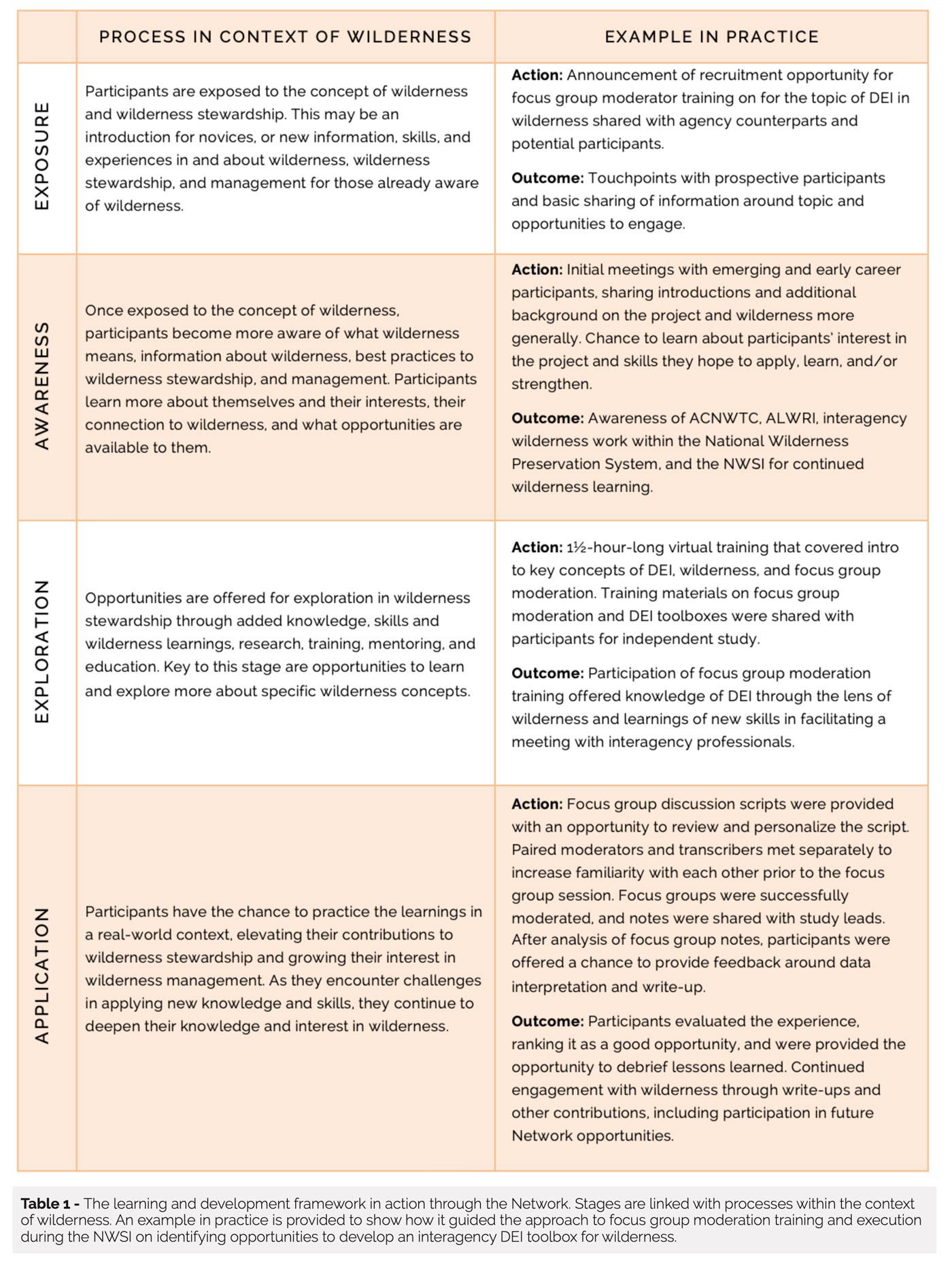

The Network provides emerging and early career professionals opportunities to be wilderness stewards through a learning and development framework with identified stages: exposure, awareness, exploration, and preparation. My experience working with workforce development programs and college and career-ready programs in public school systems provided a frame- work from which to build from. I have taken my experiences in various college and career-ready programs and combined, expanded, and redefined them within the context of emerging and early career professionals and wilderness. Regardless of whether these emerging and early career professionals stay working in wilderness, the Network offers them the opportunity to learn more about wilderness stewardship and gain professional development experience. They can carry knowledge of wilderness forward in their careers, while the wider wilderness community benefits from learning more about initiatives and experiences from different contexts and perspectives.

The learning and development framework provides emerging-early career professionals a continuum for applied learning, and they may go through one or more stages at any given time. Stages are outlined in Figure 4.

Working with collaborators from ALWRI, I used the learning and development framework to provide an opportunity to Network participants at the 2022 National Wilderness Skills Institute (NWSI) in “A Conversation about Unpacking Barriers to Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) in Wilderness,” a focus group session to identify opportunities to develop an interagency DEI toolbox for wilderness (see Redmore et al., this issue) (Table 1).

The learning and development framework offers a way to understand our individual and societal journey of understanding of concepts and ideas, including wilderness. It reveals that wilderness is a complex concept, in conversation with society and the managers charged with upholding laws and missions. As we address the rapidly retiring workforce, the Network offers opportunities, guided by a theory of change, to support, mentor, and include emerging and early career professionals in these conversations.

Network Impact To Date

Since I began this initiative in 2021, nearly 30 emerging and early career professionals across agencies (Forest Service resource assistants, Bureau of Land Management interns, US Fish and Wildlife Service advanced fellows, Virtual Student Federal Service intern) have worked on seven projects, and I continue to look for more opportunities to bring them onto short- or longer-term projects. Projects included

- 2022 Wilderness Interpretation, Education & Outreach virtual ACNWTC training course planning and implementation

- 2022 National Wilderness Skills Institute focus group moderation on toolbox needs around diversity, equity, and inclusion in wilderness with ACNWTC and ALWRI

- Support toward publication of an article for the International Journal of Wilderness (See Santos et al., this issue)

- Review of the Interagency Wilderness Network Learning and Development framework

- Review of the ACNWTC’s online Eppley training courses and help with the transfer of the courses to a new platform

- Recruitment of other emerging and early career professionals from US Fish and Wildlife Service and Bureau of Land Management emerging professionals’ cadre

- ACNWTC’s 2023 Wilderness Interpretation, Education, Outreach & Engagement: Where Do You Come In? in-person training planning, implementation, wilderness field trip leads

- Interagency Wilderness Messages Work Group for the regular review and update of interagency wilderness messages for agency staff

Post-experience evaluations revealed that participants had high levels of satisfaction with the experience, with almost all reporting that they would be interested in engaging in future opportunities around wilderness specifically, and in research and training more generally. Emerging and early career professionals who participated in the 2022 NWSI focus group moderation offered important insights about DEI in wilderness, sharing, for example, that, “I learned that lack of DEI concepts are a real barrier to wellness, and further down the line, the overall positive culture and mission of the agency.” Furthermore, their reflections on their experiences provide critical insights, for example, “Defining ‘wilderness’ is very important to begin these [focus group] sessions,” a sentiment that reveals that even at wilderness-specific events, like the NWSI, wilder- ness is not a singular, monolithic term – something that may be taken for granted by managers who are more advanced in their careers in wilderness. Emerging and early career professionals see value in the Network, and my work has been enriched and made more impactful because of their participation.

Next Steps for the Network

As I reflect on the work to connect emerging and early career professionals with wilderness, there are many opportunities to build from lessons learned during the last two years. Specifically, efforts to reach out to agency programs managers about potential opportunities for emerging and early career professionals will continue to ensure that up-and-coming managers can engage early and often with wilderness. Furthermore, there are many opportunities to expand the Network to incorporate key partner organizations, such as Outward Bound Adven- tures, Southern Appalachian Wilderness Stewards, and the Society for Wilderness Stewardship, among others. These and other nonprofit organizations play a large part in connecting emerging and early career professionals to the wilderness community at large, especially given the important role of civil society.

Overall, there are significant opportunities to continue to refine the Network with the help of the emerging and early career professionals. With their input, we can shape the future of wilder- ness opportunities for the emerging workforce as retirements continue to accelerate. It is more important than ever to ensure continued wilderness stewardship, and a stewardship that reflects the changing demographics of our nation. The ability of our next generation of workers to stew- ard wilderness is dependent on many collaborative efforts of the land management agencies, ACNWTC, ALWRI, and other wilderness conservation organizations. Finding and connecting emerging and early career professionals to wilderness community is key for the continued relevance of wilderness and our ability to steward wilderness for future generations. Emerging and early career professionals offer valuable perspectives, lived experiences, and professional experience that could be leveraged through partnerships, and the Interagency Wilderness Network is a choice for agencies to support and build current and future wilderness stewards.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Sydney Fox-Middleton and Cecelia Fox-Middleton, who inspire and offer valuable perspectives as do all Generation Z emerging-early career professionals on what it means to

be a wilderness steward “for the permanent good of the whole people.” Thank you to Lauren Redmore who early on stepped in as a collaborator to help take the Interagency Wilderness Network from an idea to fruition. I am also grateful to Cassidy Bazley, Katherine Haveman, and Moniqu Rea, who were the first to experience the Interagency Wilderness Network for Emerging and Early Career Professionals as Forest Service resource assistants and now have successfully moved on to permanent positions. They continue to contribute their valuable insight and experi- ence to the Network.

About the Authors

KIMM FOX-MIDDLETON is the wilderness interpretation and outreach specialist at the Arthur Carhart National Wilderness Training Center. She is an Environmental Professionals of Color member and former diversity, equity, and inclusion trainer for the National Park Service’s Pacific West Region; email: kimm_ fox-middleton@fws.gov.

References

Weisner, M. 2022. Federal government has so far escaped attrition crisis, but retirement wave looms. Federal Times. https://www.federaltimes.com/management/2022/08/04/federal-government-has-so-far-escaped-attrition- crisis-but-retirement-wave-looms/.

Wilderness Act. 1964. Public law, 88, 577.

Read Next

Reflections on Wilderness 60 Years after the Civil Rights and Wilderness Acts

America’s dominant narrative of the origin of a beloved wilder- ness often centers Aldo Leopold in a heroic fight at the turn of the century against rapid industrialization that occurred at the expense of nature.

Removing the Wilderness Illusion: Emerging Professionals Explore Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility in Wilderness

From the eyes of four emerging professionals in land management come four different wilderness stories.

Medicine Fish Is Leading the Way to Heal, Build, and Inspire Menominee Youth through the Wild and Scenic Wolf River: An interview with Bryant Waupoose Jr., Founder of Medicine Fish

From a bird’s eye view, the Menominee Reservation is a forested oasis in sharp relief from neighboring landscapes of dairy farms spanning northeastern Wisconsin.