Alpine Lakes Wilderness. Photo credit: Lauren Redmore.

Toward an Interagency Toolbox for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Wilderness: Findings from Five Focus Group Discussions with Wilderness Professionals

by LAUREN REDMORE, KIMM FOX-MIDDLETON, KEREN-HAPPUCH CRUM, MARGARET GREGORY, CASSIDY MOTAHARI, MARY POWERS, RUBY SAINZ ARMENDARIZ, AMANDA GRACE SANTOS, and LEA SCHRAM von HAUPT

Communication + Education

December 2023 | Volume 29, Number 2

PEER REVIEWED

ABSTRACT US federal land management agencies serve the American people and work to ensure that all Americans connect with and value wilderness. As a result, wilderness managers may prioritize diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), though may lack wilderness-specific tools and resources to foster commitments to DEI. As agencies and organizations turn to virtual resources to share information – what we refer to as toolboxes – questions remain about their utility and potential to impact DEI outcomes in wilderness. This article describes the process and results of five virtual focus group discussions with wilderness managers and key partners aimed at better understanding DEI toolbox–related needs, as well as the limitations of a DEI toolbox and opportunities to maximize potential impact of any DEI-related efforts. Key findings highlight that an interagency DEI toolbox for wilderness management could collate resources and lessons learned from innovation happening across the National Wilderness Preservation System. Yet wilderness-specific DEI goals are currently ambiguous and would benefit from clear articulation to track the impact of efforts. Participants emphasized needing leadership support and funds to advance innovation and partnerships with diverse organizations. Findings also highlight challenges associated with recruiting and retaining a diverse workforce, and navigating a wilderness culture that some participants feel has sidelined diverse connections with and stewardship of wilderness. A DEI toolbox could benefit practitioners – but could be most impactful if considered as complementary to other federal initiatives seeking to diversify workforces, fund innovation, and grow partnership with organizations representing underserved communities.

Keywords: National Wilderness Preservation System; diversity, equity, and inclusion; focus groups; virtual toolbox; partnership; funding; wilderness culture

In 2021, the White House issued the Executive Order on Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility in the Federal Workforce to address persistent gaps in employment and workplace advancement opportunities for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) and other underserved people. Decades of initiatives to recruit and retain a diverse workforce have largely fallen short of desired goals (Lee et al. 2021; Naff and Kellough 2003; Westphal et al. 2022). There are many justifications for the value of ensuring diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) within the federal workforce, and many of them center the US government’s ability to effectively develop, deliver, and administer programs, goods, and services to the American people (Batavia et al. 2020; Brown and Harris 1993).

DEI-related issues penetrate beyond the workforce and across society. Historically, a wide array of US federal policies dating back to the founding of the country have resulted in many BIPOC communities significantly losing their lands while the federal estate expanded (e.g., Nash 2019; Nash 2014; Wilson 2020). Even when BIPOC communities were not directly removed, social, cultural, religious, and livelihood practices were often criminalized, resulting in profound alienation from their relationships with the land and each other (Adlam et al. 2022; Brewer and Dennis 2019; Dent et al. 2023; Lee et al. 2022). Today, underserved communities lack access to public services, including public lands, leading many public lands managers to question whether and how public lands serve the American public (e.g., Bradshaw and Doak 2022; Flores et al. 2018; Johnson et al. 2007; Taylor 2000; Washburne 1978). BIPOC people, people with disabilities, LGBTQIA+ people, and other underserved Americans have long experienced and continue to experience discrimination and marginalization, shaping people’s access to and use of public land today (e.g., Dietsch et al. 2021; Schmidt 2021; Schultz et al. 2019; Stanley 2020).

This knowledge has led to the proliferation of programs, initiatives, and efforts seeking to redress injustices and harms disproportionately born by underserved communities (Callahan et al. 2021; White House 2022). This includes federally designated wilderness where questions of relevancy and access for underserved communities are now priority issues (Taylor et al. 2023a). The National Wilderness Preservation System offers the highest protection to 111 million acres of our nation’s public lands. Wilderness management focuses on preserving the land as “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain” (Wilderness Act 1964, section 2c). Some scholars have interpreted this orientation as situating people outside of nature and perpetuating ideas of pristine wildness visited temporarily to restore oneself from the stresses of human society (Cronon 1996; Holmes n.d.). Yet culture and society construct wilderness, an understand- ing reflected in the full title of “An Act to establish a National Wilderness Preservation System for the permanent good of the whole people, and for other purposes.” As more diverse voices are sought out, heard, and included – through partnerships, visitation and more – wilderness itself may be reshaped by new practices, interpretations, and values.

In May 2022, we held a series of virtual focus groups at the second annual virtual National Wilderness Skills Institute (NWSI), an annual coming together for training and conversations around various topics of importance to wilderness management professionals. We wanted to better understand:

- What do wilderness management professionals want from a DEI toolbox for wilderness?

- What are limitations of a DEI toolbox for wilderness?

- What are opportunities to improve the impact of a DEI toolbox for wilderness?

In this research, we do not address all facets of DEI in wilderness given how numerous, interrelated, and wide-ranging they are (see, for example, Botta and Fitzgerald 2020; Davis 2019; Rice 2022; Schultz et al., 2019). Instead, we generally examine the research on DEI trainings and toolboxes and explore the potential utility of and possibilities for developing an impactful interagency DEI toolbox for wilderness – in particular as any such effort has potential to create systemic change. Interagency refers to the four agencies charged with management of the US National Wilderness Preservation System, specifically the Bureau of Land Management, the National Park Service, the US Fish and Wildlife Agency, and the USDA Forest Service, but also considers the roles of nonprofit organizations and other key wilderness-delivery partners.

Background

The State of Knowledge on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Trainings

DEI initiatives date back to the civil rights movement of the 1960s but have proliferated in recent years in response to highly publicized instances of bias against people of color (Devine and Ash 2022). Many of these instances revolved around workplaces and workers; for instance, the 2018 Starbucks incident when a manager called the police on two Black men for sitting at a table without ordering anything (Chen 2020). Starbucks shut down their more than 8,000 stores nationwide for a mandatory half-day anti-bias training, costing the company more than $16 million in lost sales for the day (Pontefract 2018). This has led to the emergence of what some writers refer to as the DEI-industrial complex, given the size and scope of the burgeoning industry aimed at making workplaces and the services they provide welcoming to people from all backgrounds and, ideally, more reflective of the general public (Zheng 2022).

The scholarship on DEI trainings and initiatives show that they largely have mixed results. Often, they either fail to deliver long-term results or magnify problems; for example, by eroding a sense of belonging of underrepresented group members (Georgeac and Rattan 2022; Lai and Lisnek 2023). In fact, research indicates that three common DEI programs—specifically, mandatory diversity trainings, job tests, and grievance systems—create a sense of resentment amongst managers, disincentivize participation, and decrease representation (Dobbin and Kalev 2016). This means that many DEI programs may actually make companies less, not more, diverse (Dobbin and Kalev 2016). Some authors criticize DEI initiatives for leveraging a sense of urgency to push through poorly understood trainings and practices, a problem that underscores the depth of white supremacy culture in some organizations (Glass 2023; Jones and Okun 2001).

Cox (2022) argued that many DEI initiatives fail when trainings are developed from an infor- mation deficit approach. This approach assumes that people fail to adopt desired behaviors because they lack the knowledge that could initiate a change in behavior. Instead, Cox offered that empowerment-based approaches, whereby people are empowered with tools and skills to identify and reduce bias within themselves and others by breaking cycles of habits, may lead to more impactful changes (Cox 2022). In this way, the development of goals and indicators may be most empowering and impactful when they are adaptive and driven from the bottom up, either with the workforce writ-large or with communities most impacted by inequitable practices (Petri- ello et al. 2021). Well-defined DEI goals and metrics, scholars say, should account for differences across scales of impact and the interactions across those nested scales (Hinton and Lambert 2022). While some outcomes are easy to measure – for example hiring, retention, and pay – others – especially culture and bias – are difficult to measure and often require complementary approaches of examination (Davenport et al. 2022; Hinton and Lambert 2022).

Furthermore, scholars and practitioners increasingly recognize the need to change systems rather than individuals operating within the system (Melaku and Winkler 2022; Mitchneck and Smith 2021). Systems of operation are often invisible and taken for granted. These include formal and informal rules and practices, the costs and benefits of institutions and infrastructure, and historical injustices and their legacies, among others (Fleischman et al. 2014; Fukuyama 2016; Ostrom 2015; Schlosberg 2004). Yet, as Devine and Ash (2022) point out, most evaluations of DEI work are done at the individual level immediately following a training, rather than at the systems level over a longer period of time. This highlights an important gap between creating lessons and tools and ensuring their effective deployment and impact.

A Need for a Collection of DEI Tools and Resources for Wilderness?

Much of the growth in the now multibillion-dollar DEI trainings industry has focused on employee resource groups and related trainings (Research and Markets 2022). Yet there has been increased interest and support for the creation of more passive DEI resources in recent years, including toolboxes and toolkits, leading to a proliferation of online resources where the depth of impact is likely unknowable. To our knowledge, no shared definition for a virtual DEI toolbox or toolkit exists beyond a place where tools are organized and kept. However, toolboxes and toolkits share many characteristics – including collating or creating a variety of definitions, exercises, activities, case studies, and more. Many examples of DEI toolkits are freely available online; we share some below, in Table 1.

It is within this context that we define a toolbox as a collection of skills, information, and prac- tices concerning a specific area of interest – in our case, DEI in wilderness. We conducted this research on behalf of interagency wilderness commitments to DEI, and in response to a specific ask from the USDA Forest Service Wilderness Advisory Group (WAG) and Wilderness Information Management Steering Team (WIMST). Specifically, in concert with other federal initiatives to cre- ate DEI toolboxes and toolkits to share resources, data, and best practices to help advance DEI directives across agencies, WAG and WIMST approached the first two coauthors, Redmore and Fox-Middleton, about identifying the needs of interagency wilderness management professionals in a toolbox for DEI in wilderness.

Wilderness Connect (https://wilderness.net) is an interagency website and an authority for wilderness-related information. The site hosts a variety of toolboxes aimed at supporting on-the- ground wilderness management (https://wilderness.net/practitioners/toolboxes/default.php). Yet the current format of these toolboxes may limit their utility given the breadth and depth of DEI-related topics as compared to other wilderness-management topics; for instance, air quality, night skies, signs and posters, and other issues that may offer more generalized principles. By contrast, DEI-related issues are nuanced and multifaceted, spanning social scales from indi- vidual psychology to community and culture to institutional. Therefore, WAG and WIMST wanted to know what managers need to address complex DEI-related issues in wilderness and how these needs might lead to a novel interagency toolbox. This is the first effort that we are aware of to explore needs, limitations, and opportunities to create and collate DEI tools within the context of federally designated wilderness.

Methods

Focus Group Moderator Recruitment and Training

To address the research questions, we used focus group methodology to gain a deeper understanding of experiences of wilderness managers. Focus groups are useful to gain both a breadth and depth of understanding, given that participants can be in conversation with each other (Krueger and Casey 2002). To maximize the number of participants and focus group sessions, Redmore and Fox-Middleton recruited 11 Forest Service resource assistants (RAs) to assist with focus group moderation and transcription. RAs were members of an internship program recruiting diverse talent into the agency, as a part of the Interagency Wilderness Network for Emerging-Early Career Professionals, an initiative started by Fox-Middleton to connect future land managers with wilderness experiences (see Fox-Middleton, this issue).

Nine RAs attended a one-and-a-half-hour-long virtual training on May 20, 2022, where they learned about DEI, wilderness, and focus group moderation – many learning about these topics for the first time, a limitation explored below. Two RAs watched a recording of this training. Prior to the training, all RAs received training materials on moderating focus groups and examples of DEI resources developed by other organizations (Table 1). Redmore assigned RAs as either group moderators or transcribers and provided teams with interview scripts several days before the focus group to familiarize themselves with the guiding questions.

Participant Recruitment and Selection

As part of NWSI online sign-ups, potential participants indicated their interest in the ses- sion titled “From Knowledge to Impact: A Conversation about Unpacking Barriers to Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) in Wilderness.” To maximize the agencies represented, we grouped the names of 84 potential participants based on their workplace, specifically: whether they were affiliated with a federal land managing agency and which one, and whether they were affiliated with federal partners, including city and county parks, recreation departments, tribal nations, nonprofits, or universities. Using a stratified random sample approach, we selected a priority list of 40 invitees total from the four land management agencies and partner organizations by type (Bernard 2006). We notified invitees of their selection and requested them to RSVP to maximize attendance. If invitees responded that they could not attend, the researchers selected additional names from a wait list until 30 invitees confirmed they could attend, ensuring three to five participants per group (Marques et al. 2021).

All invitees were organized according to professional affiliation and job titles into different focus groups around the following five spheres of influence, or areas where wilderness managers have some ability to influence outcomes (Figure 1). These included individuals working in the sector; organizational, both federal land management agencies and nonprofit partners; with wilderness- adjacent communities; and with visitors and prospective visitors.

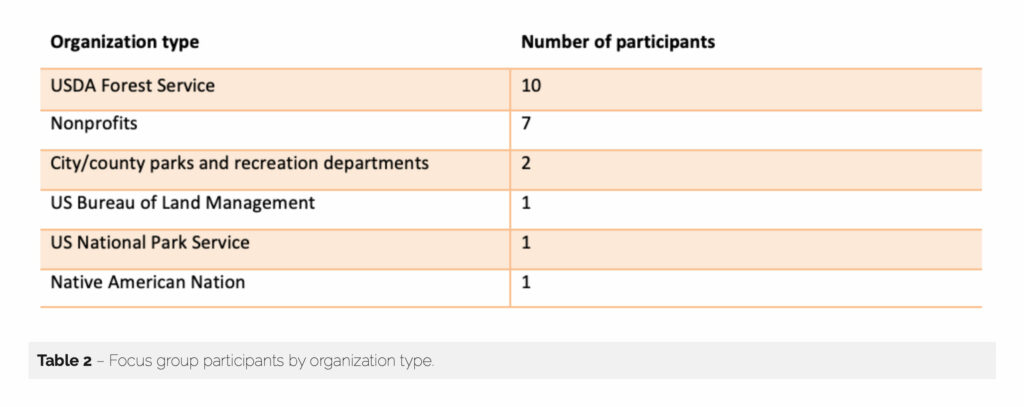

We asked invitees to browse five virtual DEI resources prior to the session to consider which aspects they thought were effective in delivering tools to improve DEI awareness. To maximize participation, the researchers sent a reminder email to each potential attendee two days before the session. Ultimately, 22 participants attended (Table 2), representing the following organization types:

Organizational representation was skewed toward Forest Service employees and nonprofit partners given the role they played in funding, organizing, developing, and delivering content for the NWSI. We consider methodological limitations in the discussion, below.

Focus Group Discussions

Overall, the session lasted 80 minutes. During the first 15 minutes, we explained the purpose of the session; key definitions on diversity, equity, and inclusion; and spheres of influence. The breakout sessions lasted approximately 60 minutes and were moderated and transcribed by the RAs. Since the researchers did not record sessions, RAs transcribed conversations as close to word-for-word as possible. The breakout sessions closed after 60 minutes, which allowed five minutes for close-out discussion.

Data Analysis

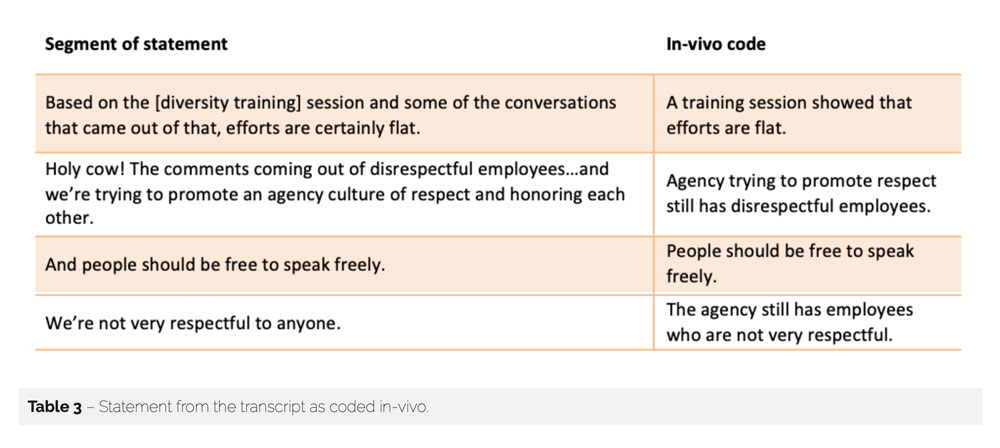

Transcripts were analyzed using a three-step approach. First, transcripts were uploaded in NVivo software. We used an in-vivo coding approach whereby each sentence of each transcript was labeled according to the main idea communicated (Glaser and Strauss 1967). In this way, each code came directly from the transcripts, line-by-line where possible, generating a list of 169 codes in total. For example, a federal government participant explained that:

based on the [diversity training] session and some of the conversations that came out of that, efforts are certainly flat. Holy cow! The comments coming out of disrespectful employees… and we’re trying to promote an agency culture of respect and honoring each other. And people should be free to speak freely. We’re not very respectful to anyone.

This statement was segmented into five codes, described in Table 3 below.

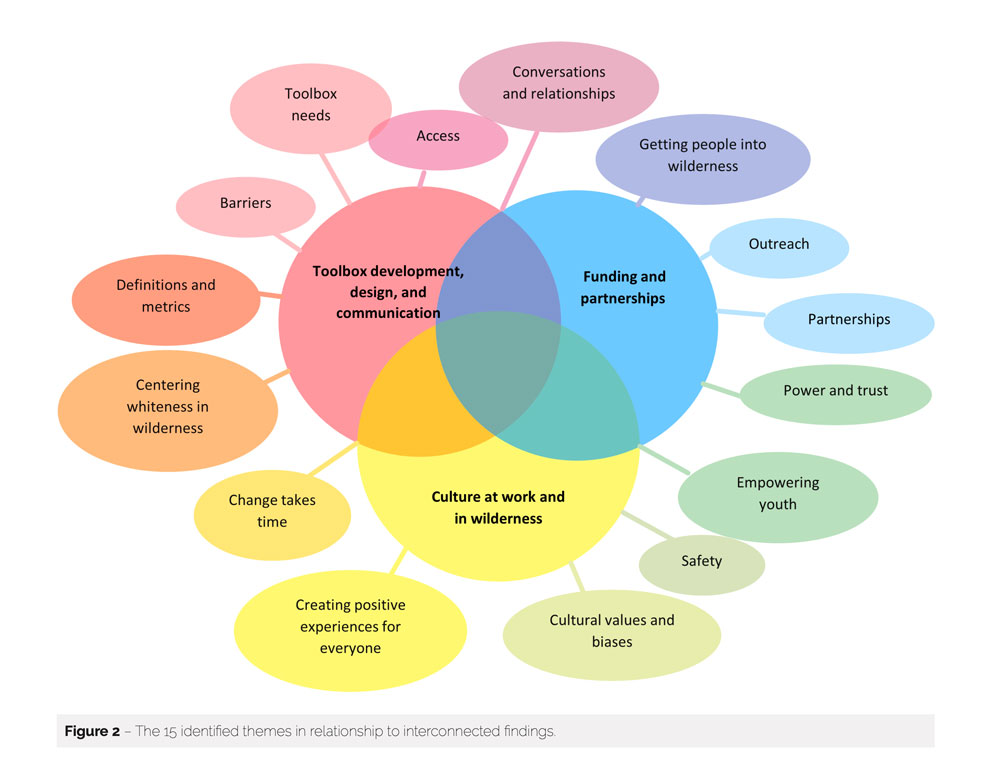

Next, all codes were organized into 15 themes, based on what the interpretation of intention was behind each code (Charmaz 2006). For instance, the codes for the above statement were grouped into the theme “cultural values and biases.” Using an approach to qualitative data analysis as part science and part art, these themes were reorganized and condensed into the three key, interrelated findings presented in this write-up (Figure 2) (Bernard 2006; Wolcott 2005). In this way, the findings highlight not only the utility and limitations of a DEI toolbox for wilderness but also the potentially transformative role of partnerships and culture in supporting a more inclusive and diverse wilderness idea. The write-up was shared with all participants and RAs to ensure accuracy of data and interpretation and to ensure that participants felt that the key themes reflect their own understanding of the focus group discussions (Candela 2019).

Findings

Toolbox Development, Design, and Communication

Participants had varied perceptions of the utility of a toolbox for DEI in wilderness. Some participants noted that toolboxes often overwhelm with their amount of information and when they lack a roadmap for moving ideas into practice; additionally, some participants failed to see how a toolbox could help address DEI issues in wilderness. One participant noted that a DEI toolbox risked creating another echo chamber for wilderness managers who are inclined to engage in this work already. Some participants noted leadership support and agency buy-in as critical to developing a toolbox and ensuring it leads to change. Some key recommendations from partici- pants for an interagency toolbox included

- Using graphics and easy-to-digest information rather than long narratives

- Integrating extensive information on the website while linking to limited hand-picked resources (e.g., the TREC toolkit, US Census Bureau)

- Ensuring equal access, which improves relevancy of and representation on public lands

- Highlighting case studies that illustrate step-by-step processes improving DEI outcomes

- Offering both online and in-person opportunities to agencies and partners, in addition to information and resources for staff and partners at various phases of the DEI journey

- Considering cultural diversity and linguistic inclusivity, especially for underserved wilderness- adjacent communities. Examples include asking how diverse groups may differently interact with wilderness and posting signs in different languages.

Some participants noted that they struggle to communicate why equity work is important for wilderness – something that could be helped by a toolbox – while others noted that DEI-related goals for wilderness have yet to be clearly articulated at both national and local levels. One participant shared that, although this work takes time and is slow-moving, metrics could help establish accountability and track progress:

A lot of these things have been occurring in relatively recent history. It takes time to see. And because it takes time, I think really important aspects are that if we have higher initiatives or training or whatever, that there’s metrics to track how many people are showing up for those trainings, how many people were hired. Metrics to track success over time and also to have a definition of what success is supposed to look like attached to those metrics so that over time we can say if we’re successful or not, or if it’s just kind of languishing.

Several participants mentioned the need for articulating common goals for DEI work, though also noted that exact metrics would vary from place to place based on demographics. One participant commented that diversity includes age, gender, and more, which complicates identi- fying appropriate metrics. Additionally, one participant said, “It’s important to listen and advocate for a more nuanced take,” reflecting that quantifiable metrics are strengthened by qualitative approaches tracking inclusion and belonging in wilderness.

To ensure that a DEI toolbox captures diverse and holistic goals, one participant emphasized the importance of co-creating with partners to amplify those already advancing DEI work. Several participants rhetorically asked, “Who’s involved in the conversation?” and, “Who’s at the table designing these programs?” further emphasizing the need for multiple perspec- tives. Another participant elaborated that any DEI effort must be coupled with a genuine power transfer, saying, “Change requires challenging the power balance. It’s hard for people to let go of. There’s lots of gatekeeping, and getting past that is hard.” Participants generally supported building a toolbox for DEI in wilderness but wanted to ensure high-level administrative support for the effort, careful articulation of goals and metrics, and collaboration with diverse partners with proven DEI impact. Together, these factors could ensure a quality product reflective and inclusive of a diverse America.

Funding and Partnerships

Many participants noted the shortcomings of a toolbox alone and emphasized the role of adequate funding and partnerships to connect the toolbox to on-the-ground outcomes. First, participants spoke to the need to adequately fund wider DEI efforts in tandem with a DEI toolbox across all wilderness managing agencies. One participant suggested that agencies:

take a hard look at your policies and see what’s missing there. Do you have inconsistent policies from one department to another? And really are you backing it up with funding for it? Because you can have all the policies in the world that you want, but if there’s not funding to implement those policies, you fall short.

Participants mentioned the role of funding to advance innovations in DEI-related work. Innovations mentioned included programs to help reduce costs for outdoor gear or funding a gear library; offering free entrance permits for residents at a community library; providing grants to reduce transportation costs to bring underserved community members to wilderness areas, allowing them to connect to place; and supporting empowering outreach and education programming, especially for youth. Several participants noted the limits of outreach work; one participant explained, “I think that outreach probably doesn’t go far enough because I, personally as a visitor of these areas, have never even experienced that outreach and I’m actively seeking it out.” Intentional and targeted outreach efforts could be more impactful than offering general information for visitors.

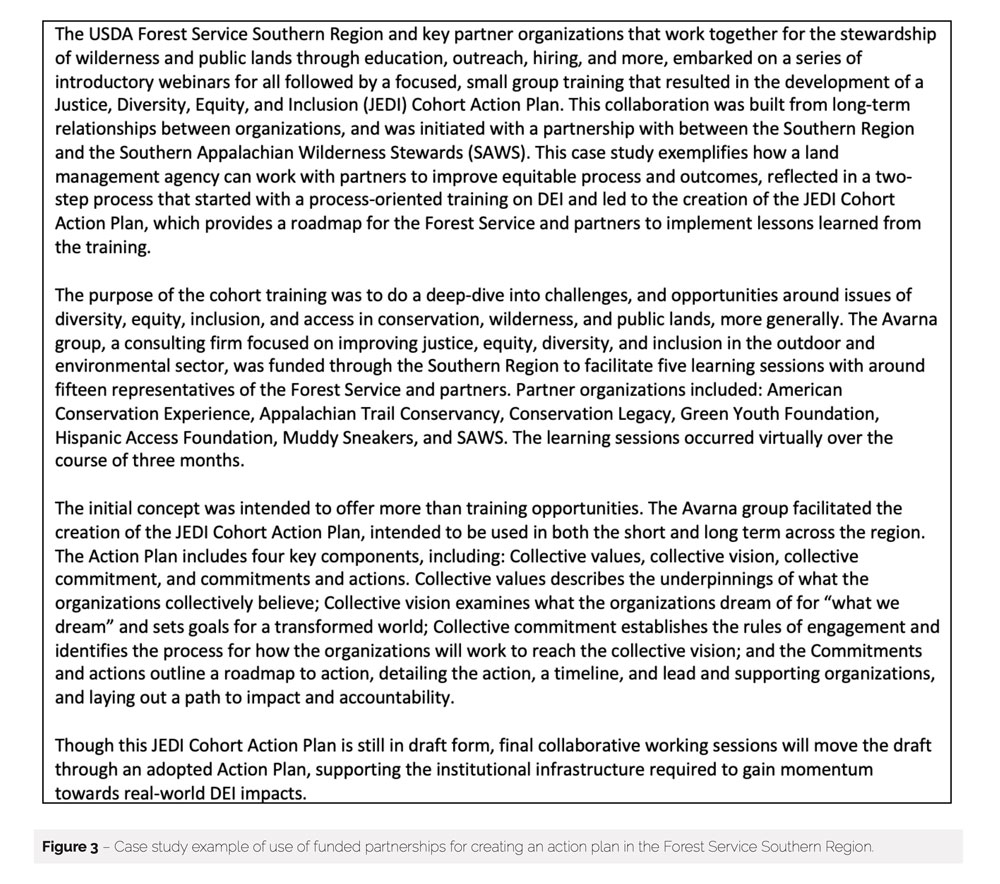

Many participants emphasized that leaning into partnerships – and allocating additional fund- ing to do so – could help land-management agencies learn from DEI experts (see Figure 3). For example, one Forest Service employee suggested that

the Forest Service should invest in paying people to train others on DEI. Giving a qualified person this specific role. They could analyze problems in the Forest Service and better represent the public. They could train the district. It should be someone that is outside the office and actually knowledgeable on DEI.

Participants believed that staff turnover compounds limited DEI expertise within federal land management agencies and prevents relationship building with communities. Instead, many participants recommended that land management agencies lean into partnerships with local organizations and groups that have established relationships and trust with underserved communities. As one participant elaborated,

I know that partnerships are really important because, you know, you connect with people. Not only with people who are already interested in the outdoors, but people who just don’t really know about it and just start with maybe not being as, I don’t know, excited about it originally just because they haven’t really been exposed to it. So that trust with a partner like a church group or something and, you know, if they bring it up, they already have those relationships with those groups.

Participants from the nonprofit sector expressed the difficulties they face securing funds for DEI work in wilderness, in particular given that donors do not always understand the value of DEI work. One nonprofit participant explained, “We lean on volunteers a lot, who lack the capacity to focus on this topic. We have to get funding and donors, and it’s the first thing to fall off the radar, especially with smaller nonprofits.” Given this challenge, federal funding could help close financial gaps and ensure DEI work in wilderness remains prioritized.

Culture at Work and in Wilderness

Many participants emphasized workforce culture and a lack of diversity as barriers to improv- ing DEI outcomes in wilderness. Additionally, they noted that people’s values of and experiences in wilderness are shaped by the often-exclusionary history of the wilderness movement. Specifically, some participants expressed that wilderness workforce culture hampers DEI efforts. Wilderness workforce culture often fails to prioritize DEI efforts, and agencies and partners generally lack diversity within their ranks. For instance, one participant who spent her career with the Forest Service expressed, “I haven’t had local or regional opportunities to discuss DEI. It’s important that the agency gets with the times because it is disappointing to work with close- minded individuals and makes me feel like I can’t contribute much to the conversation right now.” A few participants mentioned offensive, sometimes anonymous, comments made during training or awards programs for federal employees and partners. One participant expressed tension between DEI work and freedom of speech, while another emphasized problems with mandatory DEI trainings for the same reason.

Yet participants noted that workforce-related issues are linked with wider wilderness-related cultural issues. For example, one nonprofit representative explained,

The chair of our DEI committee is an Indigenous woman that is lighting up and educating the board to use educational programs, webinars, and interpretive hikes to let people know about how the Indigenous people looked over the land very well for a very long time. It is walking the walk as opposed to talking the talk that will help the public and government.

Other participants similarly shared that DEI efforts could benefit from diverse hiring practices. Diverse hiring can lead to improved representation and voice, especially as federal initiatives increasingly use Indigenous knowledge to inform land and resource management. As one nonprofit participant asked, “Who are we as a nonprofit run by non-Indigenous people to come in and say this is how that land should be managed?” Overall, many participants expressed concern about the history of wilderness and how it influences current wilderness values and experiences – though participants differed about what this means in practice. For example, one participant shared the importance of “showing what Indigenous people have done successfully in the wilderness and making it clear that their views are based on different ethnic values than ours, to create an awareness that we should be more inclusive and reach out to groups that for whatever reasons don’t use the wilderness.” In contrast, another participant expressed concern about overemphasizing the history of wilderness, suggesting a toolbox “maybe not [include] the history of the wilderness because it’s the history of racism against Indigenous people because rubbing people’s noses in that doesn’t make friends and influence people very well.” Overall, many participants believed that it is critical to be forthcoming with that history to recognize how internal bias, racism, and sexism shaped perceptions and values of wilderness today.

Participants recognized how historical perceptions and values have influenced modern thought and have barred underserved people from experiencing wilderness. For instance, one participant said, “There’s a lot of legitimate reasons why there’s been this narrative told that we should be afraid of loneliness in the woods, and I think with that it’s like we have to do a lot of dismantling of those fears through education to make these places acceptable.” Another participant explained, “It is important to acknowledge the internal bias about safety that some people have.” Issues of safety in relation to other people in wilderness were mentioned in three focus groups, with participants interested in addressing both perceived and real personal safety issues for various groups to ensure wilderness can be freely enjoyed by all.

Discussion

Through targeted discussions with federal wilderness employees and key partners in wilderness delivery, we found vast DEI-related needs in this community. A DEI toolbox for wilderness could help articulate the value of DEI in wilderness – for example, by offering case studies and guiding development of metrics to track progress – and can offer a space to share best practices and lessons learned. These findings echo the wider body of literature on DEI trainings that emphasize the need for metrics and accountability to understand, evaluate, and ensure progress toward goals (e.g., Davenport et al. 2022; Taylor et al. 2023b). Yet this may be challenging given vast biologi- cal, ecological, cultural, historical, and social differences across the National Wilderness Preservation System. For example, wilderness in Alaska has different opportunities and challenges, and likely requires a different set of approaches and tools from wilderness in Puerto Rico. Metrics and desired outcomes that incorporate a nested approach could allow for locally, regionally, and nationally relevant metrics to help track toward progress (Hinton and Lambert 2022).

Furthermore, through collaboration with external partners, wilderness managers can develop meaningful and representative goals and metrics. This could also create an opportunity to develop a toolbox that focuses on approaches, processes, and resources rather than specific outcomes. Given the differences across geographies and contexts, a toolbox alone cannot address all the challenges and needs of the wilderness community. Through an emphasis on approaches, processes, and resources – for example, the case study from figure 3 – a toolbox can be more adaptable across diverse wilderness contexts and communities. Prior research has shown the value of providing highly motivated, socially connected, and well-respected individuals or groups with tools and opportunities to initiate equitable change within their network (Forscher et al. 2017; Paluck et al. 2016). Our findings similarly emphasize that strategic partnerships backed by funding might help facilitate important conversations and change at the ground level. In this way, a more collaborative approach through funded partnerships can bolster institutional change (Bidwell and Ryan 2006).

A DEI toolbox that engages a diverse group of partners and end users, especially from Tribes, other underserved communities, and local community groups, could further bolster federal commitments already underway to make wilderness more representative of the diversity of America.

We also learned that, for some wilderness managers, the culture at work and the wider culture of wilderness can feel marginalizing to diverse ways of relating to nature. This finding aligns with other research on DEI that emphasizes the importance of shifting culture to impact bias (Glass 2023; Romero et al. 2022). Specifically, participants expressed that workforce culture sometimes hinders hiring and retaining employees with new points of view and relationships with the land – the very people who can help create change from the inside. Similarly, the perception and reality of safety issues for underserved people may hinder attempts to diversify visitor demographics and people’s relationships to wilderness. Federal managers are trialing creative ways to connect with, learn from, and elevate leaders and groups from underserved communities, but could benefit from access to systematic approaches to share best practices, like a toolbox, and support to monitor progress across the wilderness system.

Our findings are limited in two ways. First, the RAs supporting this work were not necessarily experts in wilderness, DEI, or social science research. For many, this process was their first time engaging in focus group research within the context of wilderness, but it should be noted that their engagement was intentional and a part of the commitment to empower agents of change. Additionally, the heavy sampling of participants from the US Forest Service and nonprofit sector employees may have influenced what we learned about wilderness and DEI-related efforts and challenges across agencies and partners. Care should be taken to ensure that results are inter- preted as an exploratory first step to understand what are potentially impactful and appropriate measures to improve DEI outcomes in wilderness through shared tools. Future work could benefit from additional, concerted conversations to better understand the scale of the challenges and the possible benefits and limitations of DEI tools and efforts across the National Wilderness Preservation System.

Conclusion

Federal wilderness policy and practice have largely been shaped by an elite minority – but how we perceive and connect with wilderness is culturally relative. Therefore, efforts across federal land management agencies diversifying the workforce, advancing comanagement, and redressing cultural bias in wilderness programming are already moving the needle toward more equitable inclusion of diverse voices. A DEI toolbox that engages a diverse group of partners and end users, especially from Tribes, other underserved communities, and local community groups, could further bolster federal commitments already underway to make wilderness more representative of the diversity of America.

Critically, a DEI toolbox, alone, is likely to have limited impact but could offer important opportunities for engagement with diverse partners. Any effort to develop DEI tools or trainings would benefit from thoughtful collaboration with the needs and requests of wilderness managing professionals, impacted communities, and leaders of change to maximize the utility of efforts and impact. DEI efforts could additionally benefit from greater understanding of processes for the development of metrics and goals in a way that is both simple to implement but does not reduce the many intangible facets of DEI and culture to a number. Processes for developing any DEI toolbox or trainings that not only engage but also empower local users may improve imple- mentation and benefit outcomes on the ground to ensure that all people can see themselves in wilderness.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the focus group participants who generously shared their knowledge and experiences, as well as the National Wilderness Skills Institute for the opportunity to connect with practitioners from across the country. A special thanks to Eric Sandeno, Dusty Vaughn, Timothy Fisher and the Interagency Wilderness Steering Committee for supporting this effort. This work was supported in part by the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute and the Arthur Carhart National Wilderness Training Center. The perspectives in this publication are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent any official USDA or US Government determination or policy.

About the Authors

LAUREN REDMORE is a research social scientist with the USDA Forest Service Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute where she uses her training in environmental anthropology to better understand how to improve diversity, equity, and inclusion in wilderness and wildlands; email:lauren.redmore@usda.gov

KIMM FOX-MIDDLETON is the wilderness and outreach specialist at the Arthur Carhart National Wilderness Training Center. She works to expand the wilderness narrative to be inclusive and relevant through interpre- tation, education, outreach, and engagement; email:kimm_fox-middleton@fws.gov

KEREN-HAPPUCH CRUM creates equity and environmental justice maps for the US Forest Service. She lives in Oregon where she shares her love of exploring the outdoors with her family.

MARGARET GREGORY works as a science writer-editor for the USDA Forest Service Research and Development branch, where she translates complex science into accessible terms; email:Margaret.gregory@ usda.gov

CASSIDY MOTAHARI is a freelance videographer/editor and an incoming MA student at the University of Montana’s Environmental Science and Natural Resource Journalism program.

MARY POWERS is a GIS specialist with the Spatial Analysis for Social Sciences program within the Geospatial Technology & Applications Center where she uses her expertise in GIS to develop environmental justice maps to better predict where potentially underserved communities exist at a local scale to help inform land management decisions around environmental justice.

RUBY SAINZ ARMENDARIZ is a partnership coordinator with the USDA Forest Service where she works with the National Partnership Office to engage more diverse audiences in internship programs for youth, young adults, and emerging professionals.

AMANDA GRACE SANTOS is an archaeologist for the Santa Fe National Forest and studies the physical manifestations of community during transitional periods. She earned her master’s in archaeology from Boston University; email:agrsantos@att.net

LEA SCHRAM von HAUPT currently works as a NEPA planner for the Coronado National Forest, where she manages teams of resource specialists to analyze and mitigate the environmental impacts of proposed activities on public land.

References

Batavia, C., B. E. Penaluna, T. R. Lemberger, and M. P. Nelson. 2020. Considering the case for diversity in natural re- sources. BioScience 70(8): 708–718.

Bernard, H. R. 2006. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, 4th ed. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

Bidwell, R. D., and C. M. Ryan. 2006. Collaborative partnership design: The implications of organizational affiliation for watershed partnerships. Society and Natural Resources 19(9): 827–843.

Botta, R. A., and L. Fitzgerald. 2020. Gendered experiences in the backcountry. Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Edu- cation, and Leadership 12(1).

Bradshaw, K., and C. Doak. 2022. Making recreation on public lands more accessible. Notre Dame Law Review Re- flection 97, 35.

Brewer, J. P., and M. K. Dennis. 2019. A land neither here nor there: Voices from the margins and the untenuring of Lakota lands. GeoJournal 84(3): 571–591.

Brown, G., and C. C. Harris. 1993. The implications of work force diversification in the US Forest Service. Administration & Society 25(1): 85–113.

Callahan, C., D. Coffee, J. R. DeShazo, and S. R. Gonzalez. 2021. Making Justice40 a Reality for Frontline Communities: Lessons from State Approaches to Climate and Clean Energy Investment (p. 108). Luskin Center for Innovation (LCI) at the University of California, Los Angeles. https://innovation.luskin.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/ luskin-justice40-final-web-1.pdf.

Candela, A. G. 2019. Exploring the function of member checking. The Qualitative Report 24(3): 619–628.

Charmaz, K. 2006. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis, 1st ed. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Chen, S. 2020, July 14. The equity-diversity-inclusion industrial complex gets a makeover. Wired. https://www.wired. com/story/the-equity-diversity-inclusion-industrial-complex-gets-a-makeover/.

Cox, W. T. L. 2022. Developing scientifically validated bias and diversity trainings that work: Empowering agents of change to reduce bias, create inclusion, and promote equity. Management Decision, in press.

Cronon, W. 1996. The trouble with wilderness: Or, getting back to the wrong nature. Environmental History 1(1): 7–28.

Davenport, D., S. Natesan, M. T. Caldwell, M. Gallegos, A. Landry, M. Parsons, and M. Gottlieb. 2022. Faculty recruit- ment, retention, and representation in leadership: An evidence-based guide to best practices for diversity, equity, and inclusion from the Council of Residency Directors in Emergency Medicine. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine 23(1): 62.

Davis, J. 2019. Black faces, black spaces: Rethinking African American underrepresentation in wildland spaces and outdoor recreation. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 2(1): 89–109.

Dent, J. R. O., C. Smith, M. C. Gonzales, and A. B. Lincoln-Cook. 2023. Getting back to that point of balance: Indigenous environmental justice and the California Indian Basketweavers’ Association. Ecology and Society 28(1).

Devine, P. G., and T. L. Ash. 2022. Diversity training goals, limitations, and promise: A review of the multidisciplinary literature. Annual Review of Psychology 73: 403–429.

Dietsch, A. M., E. Jazi, M. F. Floyd, D. Ross-Winslow, and N. R. Sexton. 2021. Trauma and transgression in nature- based leisure. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living 3: 735024.

Dobbin, F., and A. Kalev. 2016. Why diversity programs fail. Harvard Business Review, July–August. https://hbr. org/2016/07/why-diversity-programs-fail.

Fleischman, F. D., N. C. Ban, L. S. Evans, G. Epstein, G. Garcia-Lopez, and S. Villamayor-Tomas. 2014. Governing large- scale social-ecological systems: Lessons from five cases. International Journal of the Commons 8(2): 428–456.

Flores, D., G. Falco, N. S. Roberts, and F. P. Valenzuela III. 2018. Recreation equity: Is the forest service serving its di- verse publics? Journal of Forestry 116(3): 266–272.

Forscher, P. S., C. Mitamura, E. L. Dix, W. T. Cox, and P. G. Devine. 2017. Breaking the prejudice habit: Mechanisms, timecourse, and longevity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 72: 133–146.

Fukuyama, F. 2016. Governance: What do we know, and how do we know it? Annual Review of Political Science 19: 89–105.

Georgeac, O. A., and A. Rattan. 2022. The business case for diversity backfires: Detrimental effects of organizations’ instrumental diversity rhetoric for underrepresented group members’ sense of belonging. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Glaser, B., and A. Strauss. 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research, 1st ed. Aldine Publishing Company.

Glass, L. E. 2023. Fool’s gold: DEI and the performance of race-consciousness. Contexts 22(2): 36–41.

Hinton, A., and W. M. Lambert. 2022. Moving diversity, equity, and inclusion from opinion to evidence. Cell Reports Medicine 3(4).

Holmes, T. P. N.d. Wilderness economics in the Anthropocene: Expanding the horizon. In A Perpetual Flow of Benefits: Wilderness Economic Values in an Evolving, Multicultural Society (p. 189).

Johnson, C. Y., J. Bowker, G. Green, and H. Cordell. 2007. “Provide it…but will they come? A look at African American and Hispanic visits to federal recreation areas. Journal of Forestry 105(5): 257–265.

Jones, K., and T. Okun. 2001. White supremacy culture. In Dismantling Racism: A Workbook for Social Change.

Krueger, R. A., and M. A. Casey. 2002. Designing and Conducting Focus Group Interviews, vol. 18. Citeseer.

Lai, C. K., and J. A. Lisnek. 2023. The impact of implicit-bias-oriented diversity training on police officers’ beliefs, motivations, and actions. Psychological Science 34(4): 424–434.

Lee, D., M. Johansen, and K. B. Bae. 2021. Organizational justice and the inclusion of LGBT federal employees: A quasi-experimental analysis using coarsened exact matching. Review of Public Personnel Administration 41(4): 700–722.

Lee, K. J., M. Fernandez, D. Scott, and M. Floyd. 2022. Slow violence in public parks in the US: Can we escape our troubling past? Social & Cultural Geography: 1–18.

Marques, I. C. D. S., L. M. Theiss, C. Y. Johnson, E. McLin, B. A. Ruf, S. M. Vickers, M. N. Fouad, I. C. Scarinci, and D. I. Chu. 2021. Implementation of virtual focus groups for qualitative data collection in a global pandemic. The Ameri- can Journal of Surgery 221(5): 918–922.

Melaku, T., and C. Winkler. 2022, June 29. Are your organization’s DEI efforts superficial or structural? Harvard Busi- ness Review. https://hbr.org/2022/06/are-your-organizations-dei-efforts-superficial-or-structural.

Mitchneck, B., and J. Smith. 2021, August 23. We must name systemic changes in support of DEI. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2021/08/24/academe-should-determine-what-specific-systemic-changes-are-needed-dei-opinion.

Naff, K. C., and J. E. Kellough. 2003. Ensuring employment equity: Are federal diversity programs making a difference? International Journal of Public Administration 26(12): 1307–1336.

Nash, M. A. 2019. Entangled pasts: Land-grant colleges and American Indian dispossession. History of Education Quarterly 59(4): 437–467.

Nash, R. F. 2014. Wilderness and the American Mind, 5th ed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Ostrom, E. 2015. Governing the Commons. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Paluck, E. L., H. Shepherd, and P. M. Aronow. 2016. Changing climates of conflict: A social network experiment in 56 schools. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113(3): 566–571.

Petriello, M. A., L. Redmore, A. Sène-Harper, and D. Katju. 2021. Terms of empowerment: Of conservation or commu- nities? Oryx 55(2): 255–261.

Pontefract, D. 2018, June 1. Did the Starbucks racial-bias training plan work? Forbes Magazine. https://www.forbes. com/sites/danpontefract/2018/06/01/did-the-starbucks-racial-bias-training-plan-work/?sh=2e38b32591ee.

Research and Markets. 2022, August 5. Global diversity and inclusion (D&I) market to reach $15.4 billion by 2026. PR Newswire. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/global-diversity-and-inclusion-di-market-to-reach- 15-4-billion-by-2026–301600777.html.

Rice, W. L. 2022. The conspicuous consumption of wilderness, or leisure lost in the wilderness. World Leisure Journal 64(4): 451–468.

Romero, V. F., J. Foreman, C. Strang, L. Rodriguez, R. Payan, K. M. Bailey, and S. Olsen. 2022. Racial equity and inclusion in United States of America–based environmental education organizations: A critical examination of priorities and practices in the work environment. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education 25(1): 91–116.

Schlosberg, D. 2004. Reconceiving environmental justice: Global movements and political theories. Environmental Politics 13(3): 517–540.

Schmidt, J. 2021. (De)constructing nature and disability through place: Towards an eco-crip politic. PhD diss. Wash- ington State University, Pullman, WA.

Schultz, C. L., J. N. Bocarro, K. J. Lee, A. Sène-Harper, M. Fearn, and M. F. Floyd. 2019. Whose National Park Service? An examination of relevancy, diversity, and inclusion programs from 2005–2016. Journal of Park & Recreation Administration 37(4).

Stanley, P. 2020. Unlikely hikers? Activism, Instagram, and the queer mobilities of fat hikers, women hiking alone, and hikers of colour. Mobilities 15(2): 241–256.

Taylor, D. E. 2000. Meeting the challenge of wild land recreation management: Demographic shifts and social in- equality. Journal of Leisure Research 32(1): 171–179.

Taylor, J., T. Hollingsworth, C. Armatas, K. Carim, K. Hefty, O. Helmy, L. Holsinger, D. Paige, S. Parks, L. Redmore, J. Rushing, E. Taylor, and K. Zeller. 2023a. The future of wilderness research: A 10-year wilderness science strategic plan for the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute. International Journal of Wilderness 29(1): 51–71.

Taylor, M. M., C. S. Fernandez, G. Dave, K. Brandert, S. Larkin, K. Mollenkopf, and G. Corbie. 2023b. Implementing measurable goals for diversity, equity, and inclusion in Clinical and Translational Science Awards leadership. Equity in Education & Society: 27526461231159920.

Washburne, R. F. 1978. Black under‐participation in wildland recreation: Alternative explanations. Leisure Sciences 1(2): 175–189.

Westphal, L. M., M. J. Dockry, L. S. Kenefic, S. S. Sachdeva, A. Rhodeland, D. H. Locke, C. C. Kern, H. R. Huber-Stearns, and M. R. Coughlan. 2022. USDA Forest Service employee diversity during a period of workforce contraction. Journal of Forestry 120(4): 434–452.

White House. 2022. FACT SHEET: Biden-‐Harris administration releases agency equity action plans to advance equity and racial justice across the federal government (statements) [Briefing room]. https://www.whitehouse.gov/brief- ing-room/statements-releases/2022/04/14/fact-sheet-biden-harris-administration-releases-agency-equity- action-plans-to-advance-equity-and-racial-justice-across-the-federal-government/.

Wilderness Act. 1964. Public law, 88, 577.

Wilson, R. K. 2020. America’s Public Lands: From Yellowstone to Smokey Bear and Beyond. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Wolcott, H. F. 2005. The Art of Fieldwork. Rowman Altamira.

Zheng, L. 2022, December 1. The failure of the DEI-industrial complex. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr. org/2022/12/the-failure-of-the-dei-industrial-complex.

Read Next

Reflections on Wilderness 60 Years after the Civil Rights and Wilderness Acts

America’s dominant narrative of the origin of a beloved wilder- ness often centers Aldo Leopold in a heroic fight at the turn of the century against rapid industrialization that occurred at the expense of nature.

Removing the Wilderness Illusion: Emerging Professionals Explore Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility in Wilderness

From the eyes of four emerging professionals in land management come four different wilderness stories.

Medicine Fish Is Leading the Way to Heal, Build, and Inspire Menominee Youth through the Wild and Scenic Wolf River: An interview with Bryant Waupoose Jr., Founder of Medicine Fish

From a bird’s eye view, the Menominee Reservation is a forested oasis in sharp relief from neighboring landscapes of dairy farms spanning northeastern Wisconsin.