Road leading to the Collegiate Peaks Wilderness (impassible drop‐off just past the hump in the center of the picture). Photo credit: C.B. Griffin

The Road to Wilderness Is Not Paved

by C. B. GRIFFIN

Stewardship

April 2024 | Volume 30, Number 1

Access to wilderness can mean many things, including how welcoming it is to people from all backgrounds (Ronald et al. 2023). For the purposes of this commentary, the term “access” is restricted to mean getting to a wilderness trailhead. I am conducting research on US Forest Service (USFS)-managed wilderness in Colorado. The purpose of the research is to deter- mine how accurate and comprehensive the regulations are that are posted on trailhead kiosks. My thoughts are based on having driven to approximately half of the 500 wilderness trailheads.

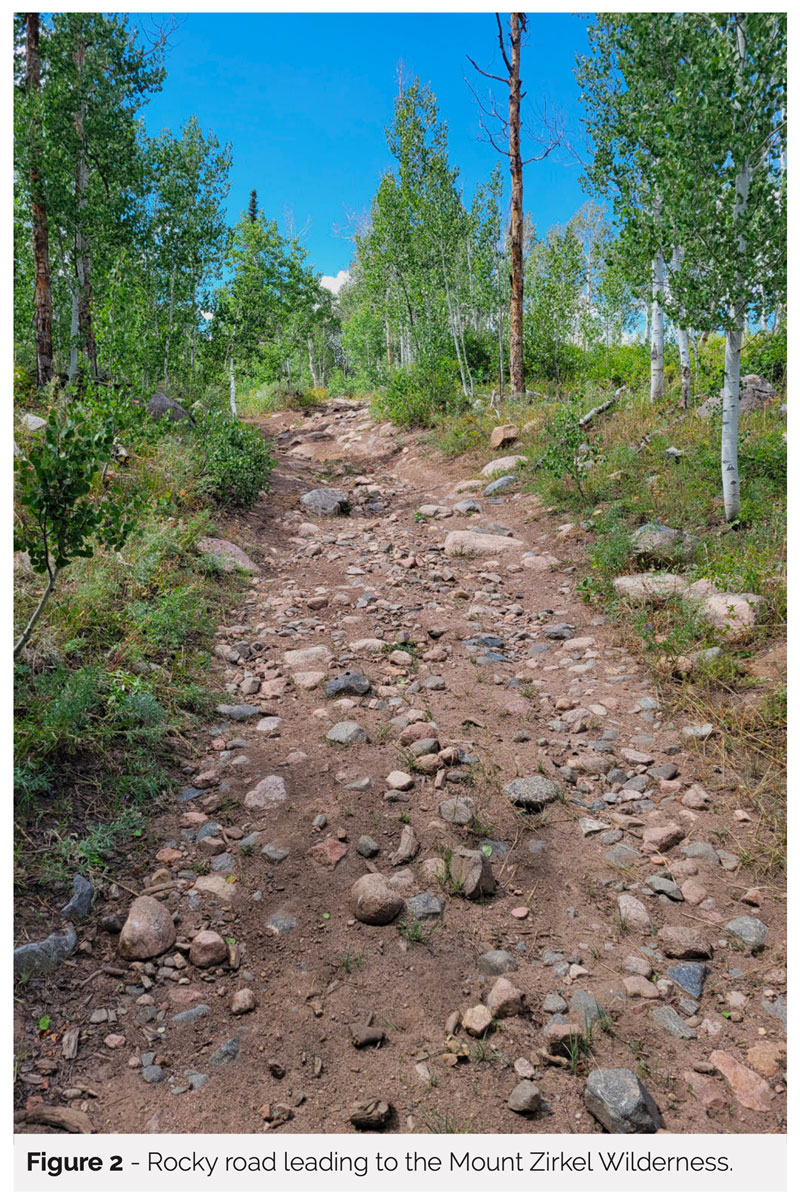

None of the trailheads I have visited have been accessible by any form of public transportation. This may be unsurprising, but it also means that access to Colorado wilderness areas is a function of the vehicle individuals have access to. What was surprising to me is the number of trailheads that are best accessed using a four-wheel drive and/or high-clearance vehicle. Some of the trailheads require an even more specialized vehicle, such as an all-terrain vehicle (ATV) that as recreational vehicles are often not permitted on conventional roadways (I hiked to these trailheads). Thus, in Colorado, the quality of the road, along with other factors, will determine how accessible wilderness is to visitors.

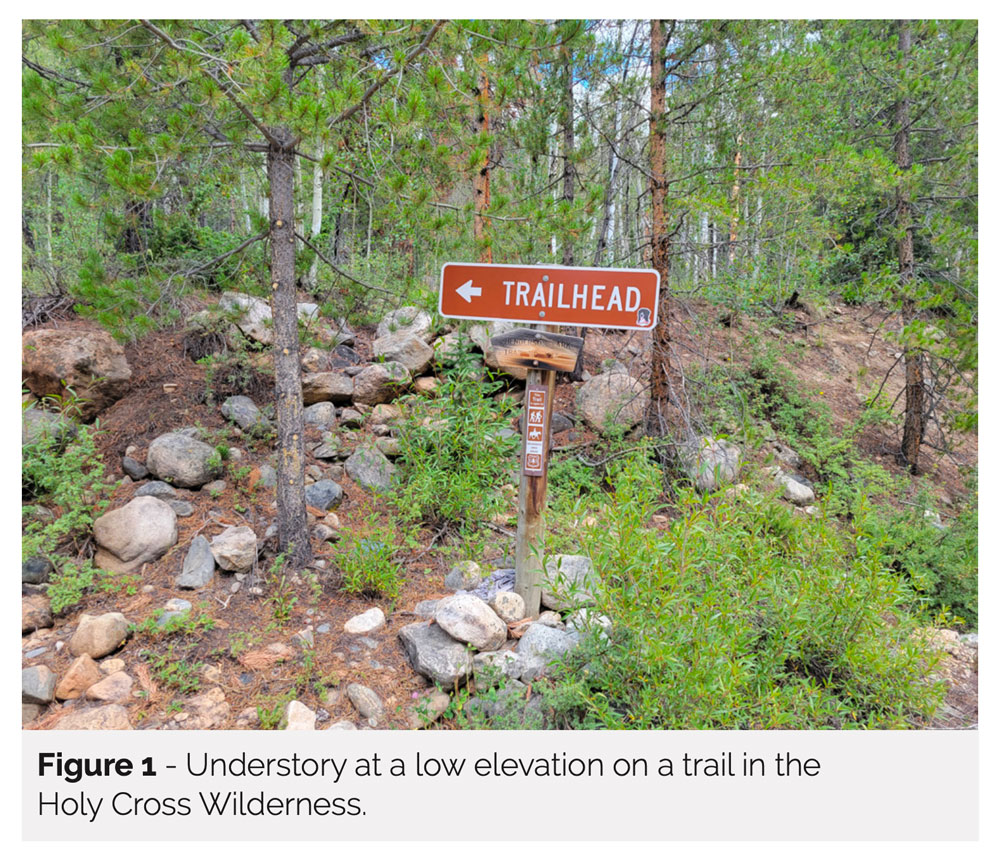

While it is true that a prospective wilderness visitor with a pas- senger vehicle can access wilderness by walking to the trailhead when their car can no longer be driven on the road, the reality is that many trailheads would require a long hike before arriving at the trailhead. While some trailheads are very near the wilderness boundary, others require even more hiking – in some cases – several miles to get to the designated wilderness area boundary. It is also true that prospective visitors can access the wilderness without a trailhead, but in practice, this is unlikely because hiking off-trail is very difficult due to the dense understory found in Colorado forests.

The USFS has several possible ways to maintain or increase wilderness access. First, they could make wilderness more accessible by focusing on increasing public transportation to wilderness trailheads. Yet there are very few places where this would work because wilderness trailheads are typically far from cities.

Second, the USFS could build more trails that have roads that accommodate passenger vehicles. However, building new trails in wilderness would seldom, if ever, survive the minimum requirements analysis.

In essence, all the trails that exist in wilder- ness are all the trails that will ever exist, barring any congressional change to the Wilderness Act.

Third, the USFS could increase the maintenance of existing USFS roads. In some cases, this would mean more road grading, while in other cases, more extensive work would be needed to fill in holes or remove rocks (Figure 2). The Forest Service would need to prioritize which roads to focus on given limited budgets. For example, they could focus on the cheapest roads to increase access (where a small section of road serves as the barrier to passenger vehicles), the most popular trailheads, or trailheads closer to cities.

The policy the USFS is using to determine where to make road, trail, and other site improvements at developed, undeveloped, and wilderness areas is based on the results from the National Visitor Use Monitoring (NVUM) surveys. If the user surveys indicate that user satisfaction is less than the importance to users, the USFS should focus on these areas. The most recent NVUM results for most of the wilderness areas in Colorado show that there is little concern about road quality (USFS 2023a). However, the surveys are only conducted on-site; thus, if a prospective visitor never made it to the trailhead because of road conditions, their opinion is not recorded.

The USFS is aware of the road quality issue as it relates to the type of vehicle needed to access some trailheads. One employee reported, “As someone who has gone to many of those trailheads (THs) I would recommend a stout 4WD with insurance. I’ve given up on reaching some of those THs to avoid damaging my 4Runner.”

While the USFS may be focusing on the strategies I described, as well as other strategies, to increase access, the current focus seems to be on improving the quality of trails, rather than improving road access. The USFS recently listed 15 high-priority areas for trail improvements, including many of the Colorado wildernesses that have one of the “14ers”: peaks that exceed 14,000 feet in elevation (USFS 2023b).

The 58 14ers (Figure 3) have always been a magnet for hikers and climbers (I have hiked 26 of them) (Sokol 2020). The trail improvement initiative is designed to improve trails with the goal of reducing the biophysical impact of people (and presumably pack-stock) on trails. Although the improvements will make it easier to find and stay on the trail and will reduce the biophysical impacts of hikers (often by hardening or rerouting the trail), they will not improve access per se. While better- maintained trails have benefits to visitors, the bigger benefit comes from reducing biophysical impacts by encouraging users to stay on a single trail. Without maintenance, users often create a braided trail system with parallel rails leading to the same destination (Figure 4).

The USFS has partnered with volunteer groups to do trail maintenance throughout the country. In Colorado, the agency has a long list of partner organizations that have helped with trail maintenance (USFS 2023c). However, liability issues are likely to prevent these volunteer groups from assisting with road maintenance. There are a few examples where the USFS has partnered with Colorado Off Road Enterprise (CORE), an off-road recreation vehicle (ORV) group dedicated to “keep offroad trails in Colorado and Utah open,” to maintain some USFS roads that provide wilderness access (CORE 2023). But the focus of these is the most extreme end of road quality; the intended user is someone with an ATV or modified high-clearance vehicle rather than someone using a passenger vehicle (Figure 5).

If the USFS decides not to improve the quality of roads, then roads will deteriorate. Benign neglect of road maintenance will have the same effect; roads that were accessible by passenger car will increasingly only be available by a high-clearance, 4WD vehicle or an ATV. Over time, fewer and fewer trailheads will be accessible to passenger vehicles.

If the USFS allocates additional resources to improving road quality, they will expand access to people owning passenger vehicles – a good thing. But, doing so may have negative effects. For example, more use may mean that additional trail maintenance is needed. Increased use will negatively affect wildlife in lightly used areas of the wilderness. There may be increased pressure on the USFS to expand parking lots. Finally, increased use will mean decreased solitude – one of the components of wilderness character.

This trade-off – between increasing access for potential visitors who do not own a high-clearance, 4WD vehicle and the increased expense of improving the access as well as the impact on the trails, wildlife, and solitude – is worth having further conversations about.

C. B. “GRIFF” GRIFFIN is a professor in natural resources management at Grand Valley State University; email: griffinc@gvsu.edu.

References

CORE. 2023. What we do. https://www.keeptrailsopen.com/what-we-do, accessed November 16, 2023.

Ronald, L., S. Ahmed, K. Bliss, J. Chakrin, T. Ekasi-Otu, K. Fox-Middleton, J. Harrington, S. Johnson, T. Mazzei, J. Mejia, and R. Osorio. Can we make wilderness more welcoming? An assessment of barriers to inclusion. 2023. Interna- tional Journal of Wilderness 29(1): 16–41.

Sokol, R. 2020. Toward sustainable recreation on Colorado’s fourteeners. University of Colorado Law Review, 91(1): 345–[xiv].

USFS. 2023a. National Visitor Use Monitoring program. https://www.fs.usda.gov/about-agency/nvum, accessed November 20, 2023.

USFS. 2023b. Trail Maintenance Priority Areas. https://www.fs.usda.gov/managing-land/trails/priority-areas, ac- cessed November 16, 2023.

USFS. 2023c. Colorado fourteeners. https://www.fs.usda.gov/managing-land/trails/priority-areas/colorado-four- teeners.

Read Next

Forgetting Your Anniversary, Again

This year represents the 30th anniversary of the International Journal of Wilderness.

The Trouble with Virtual Wilderness

How the history of the 20th-century wilderness movement might give us different moral guidance as we confront this new technology.

Revisiting Human’s Role in Wilderness

The question we must ask ourselves today is familiar: Are we guardians, or are we gardeners?