Fremont cottonwoods changing color behind saguaro cacti in Superstition Wilderness. Photo credit: Luke Koenig

Revisiting Human’s Role in Wilderness

by LUKE KOENIG

Stewardship

April 2024 | Volume 30, Number 1

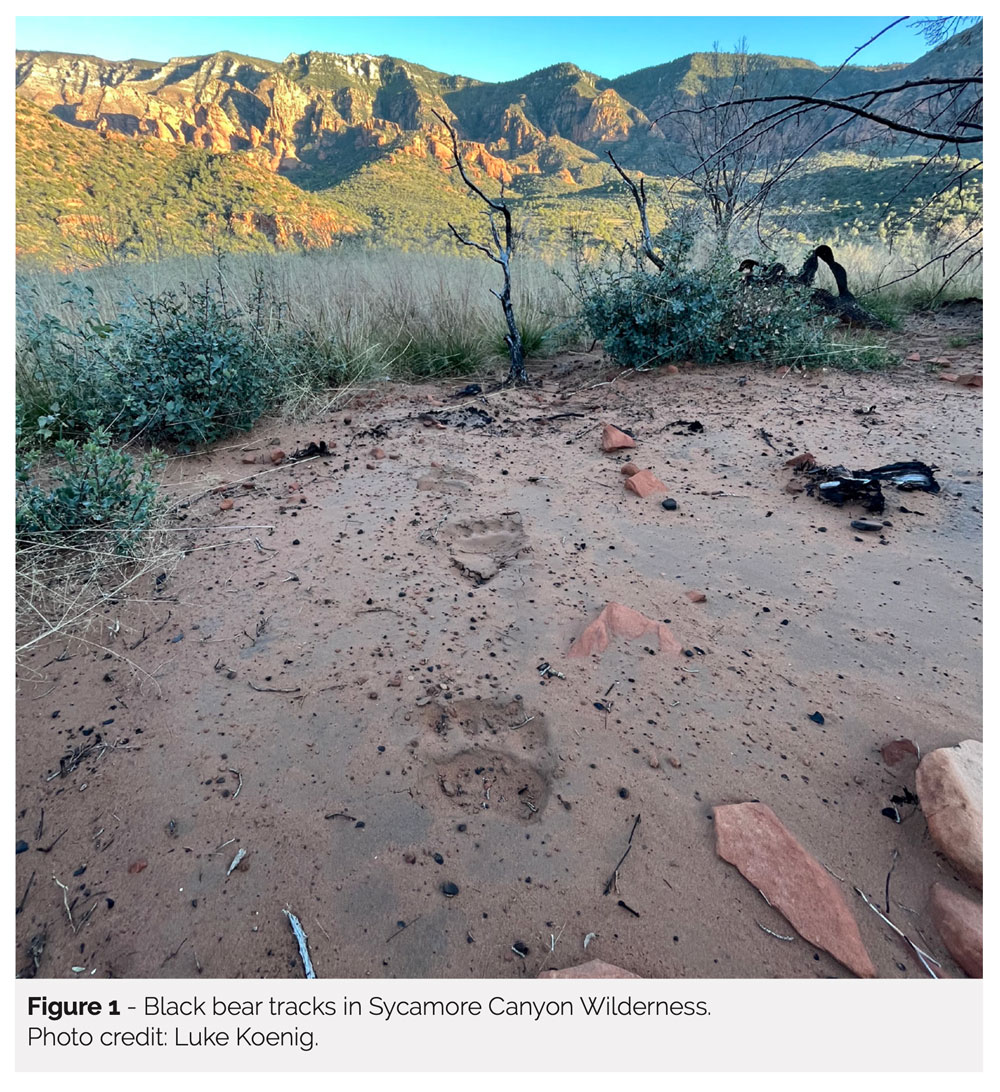

Nearly 100 years later, I work as a wilderness steward on much of the very same land that inspired some of Aldo Leo- pold’s most famous work. Nearly 100 years after one of the founders of the Wilderness Idea mourned the loss of apex predators from the region, we are still trying to find the com- munity and political support to bring them back and connect them to their former range. Over that same time, Arizona and New Mexico, like much of the US West, have seen policies of fire suppression that have led to catastrophic megafires. Invasive plants have taken over once-thriving ecosystems. And climate change poses threats to wilderness in ways unforeseeable to the framers of the Wilderness Act.

The question we must ask ourselves today is familiar: Are we guardians, or are we gardeners? When Howard Zahniser first raised this question during his drafting of the Wilderness Act, he was a staunch defender of the former (Scott 2001). But in the intervening years, since the days of Leopold and Zahniser, what has changed?

In the wake of an increased understanding of our impacts on wilderness, we are tasked with reevaluating the fundamental assumptions about our relationship to nature that underlie wilderness policy. The deeply held assumption that humans are separate from nature has led to an evaluation of wilderness quality that is dependent on that separation. However, other qualities, such as biodiversity and ecological integrity, may also be at the heart of what is worth protecting in designated wilderness areas. As these other qualities come to depend increasingly on human intervention, it is time to revisit humans’ role in wilderness from an environmental ethics lens: What are our responsibilities to wilderness, and what is wilderness for?

I am concerned that increasing calls to interpret the Wilderness Act as a fundamen- tally noninterventionist document will cause us to lose sight of what is arguably its most important function: to protect vulnerable ecosystems and irreplaceable organisms that would otherwise be wiped out.

Both Natural and Not: Multiple Definitions

The threats posed by climate change and other complex anthropogenic stressors have sparked renewed discussion on conflicting notions of “natural” as it pertains to wilderness management. While there are many possible definitions of “natural,” a particular conceptualization of the term was employed during the drafting of the Wilderness Act and continues to guide wilderness policy today. This conceptualization was informed by the cultural, historical, and ecological context in which the act was written.

If we accept that the context has changed, then we must determine whether that definition remains equipped to meaningfully address management challenges that have also changed. In the 21st century, the most contentious wilderness management question will be the extent to which we are permitted to intervene in designated wilderness to maintain the “natural conditions” that the Wilderness Act mandates we preserve. This question will hinge on how we define “natural” and the extent to which human activities fit within that definition.

At the time the Wilderness Act was written, there was good reason to think that in order to protect nature, humans must largely be kept out of it. If nothing else, the act was a reaction to the forces of development and the anthropocentric reduction of wilderness to “natural resources,” that together threatened to extinguish the last of America’s wildlands. Prior to the National Wilderness Preservation System and its precursors (e.g., the Gila Wilderness before 1964), even areas protected for natural and cultural value remained threatened by these twin forces. Roads and hotels were blighting protected areas and diminish- ing the very qualities that made them worth protecting. In effect, even when humans were attempting to preserve natural landscapes, their presence seemed necessarily antithetical to their character. Even in principle.

As Leopold wrote, “All conservation of wildness is self-defeating, for to cherish we must see and fondle, and when enough have seen and fondled, there is no wilderness left to cherish” (Leopold 1949).

In the words of Section 2(c) of the Wilder- ness Act: “A wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain . . . [Land] which is protected and managed so as to preserve its natural conditions and which . . . generally appears to have been affected primarily by the forces of nature, with the imprint of man’s work substantially unnoticeable.”

The Wilderness Act is fundamentally built on the distinction between humans and nature, but it uses this distinction as a powerful means of protection. Herein lies the real genius of the act: it can work within an existing framework of separation, a framework in which humans and nature have no reciprocal or symbiotic relationship, by doubling down on that separation. However, there are other possible ways to conceptualize humans’ relationship to nature, and other contexts that demand different conceptualizations.

As McDonald et al. (2000) write, “It is important to note that, for tribal land managers, these territories called wilderness by the settler population are thought of as homelands by the tribal peoples.” The very lands that would one day be set aside because they appear to have been “affected primarily by the forces of nature” have been inhabited and managed by humans for millennia. These landscapes were interacted with by their inhabitants in a way that was congruous with a different kind of natural, one not based on an assumption of separation, that instead recognizes humans’ roles in ecosystems. McDonald et al. continue, “[Indigenous] lands are far from untrammeled in tribal eyes and humans are certainly not intruders into nature.” (McDonald et al. 2000).

Today, while Indigenous people make up only 5% of the global population, they protect 80% of the world’s remaining biodiversity (World Wildlife Fund 2020). Wilderness is not dependent on being untrammeled in those frameworks where humans and the natural world have a reciprocal or symbiotic relationship. Though how industrialized societies manage for wilderness in the 21st century may be different from Indigenous societies; adequately preserving natural conditions in times of ecological change may similarly depend on a less dualistic assumption about our role in wilderness. Wilderness, if evaluated by ecological integrity, will not be dependent on remaining untrammeled.

No longer should we view the activities of humans as necessarily antithetical to the natural conditions that wilderness protects. The mere separation from nature that powered the Wilderness Act is no longer adequate now that anthropogenic ecological change demands active mitigation to preserve biodiversity. Not only is the binary conceptualization of natural no longer helpful for mitigating the most salient threats to wilder- ness today (climate change, invasive species, changing fire ecology), it will also hinder our ability to address them. While encroaching development and extractive industries remain significant concerns, the most pressing threat to wilderness today is the far more insidious one of catastrophic biodiversity loss brought on by complex anthropogenic stressors.

But our capacity to redefine natural depends on our ability to break free from the assumption about nature so basic that we take it for granted: that our relationship to it is dualistic – either we are a part of it or we are not.

Much like 100 years ago, our presence, in the form of our impacts, is antithetical to the natural conditions protected within wilderness areas. Yet at the same time, our presence, in the form of our ecological intervention and stewardship, is now increasingly required to preserve those very same natural conditions.

So, in 21st–century wilderness management, are humans natural or not? Framing this question in a binary way may be precisely the problem. But the answer will also depend as much on a prescriptive ethical question as on a descriptive ecological question. The extent to which our goal is to manage for wilderness biocentrically will determine the extent to which our interventions and active management will be permitted. In turn, this will inform a definition of natural that better fits a 21st-century context.

Asking the Right Questions about Our Role in Nature

The hard question we must ask ourselves today is, Do we continue to manage for natural conditions in a way that is built so fundamentally on our distinction from them that we would rather let them irrevocably deteriorate than to step in? This approach seems ethically dubious when we consider that the threats to these areas themselves are human caused. This is an ecologically reckless place to draw the line: that our impacts may be considered natural, but our mitigation of them is not.

Is it really the case that what “naturalness” requires of us is to throw up our hands and let “nature take its course?” Or does the Wilderness Act in fact implicate a paradoxical “cultivation” of wildness? I would wager that letting invasive tamarisk in the riparian zones of the US Southwest, for instance, wipe out a keystone species such as the Fremont cotton- wood, which supports the habitat of countless other native species, is not what the framers of the act had in mind (National Wildlife Federation 2023) – even if removing tamarisk requires highly intrusive intervention.

Over-privileging of the untrammeled characteristic of wilderness will require us to view wholly novel ecosystems, that reek more of human impact than anything that could have existed prior to industrialization, as somehow wilder than a thriving, intact ecosystem with all of its intricate pieces in place. Compared to the introduction of invasive weeds and the extirpation of top predators, the impacts of global-scale stressors such as climate change will be of a scale entirely their own. However, the fundamental questions we must ask our- selves of our role in wilderness remain largely the same.

Some are concerned that increased intervention and restoration will undo the spirit of wilderness, even at the cost of ecological degradation and biodiversity loss. In this context, Roger Kaye, in his 2021 essay, “Preserving the Wildness of Wilderness in the Anthropocene,” laments the use of interventions such as water impoundments, prescribed fire, herbicides, and assisted migration. He is concerned that already, “The Minimum Requirements Analysis (MRA) and its supplement for evaluating proposals for ecological interventions, tend to facilitate the agencies ‘action bias’ toward intervention.” Kaye and others hold the firm conviction that the capacity for wilderness to remain wild and adequately preserve natural conditions necessarily depends on our ability to resist the temptation to step in. This represents the noninterventionist stance.

Kaye has notably asked, “Should we strive to maintain natural conditions, that is, the products of evolutionary creativity at our point in time, or should we perpetuate that creative process itself, wildness?” (Kaye 2021). While at first glance this may sound like a compelling distinction, it is in fact a false dichotomy. Either way, wildness, in some shape or form, is going to continue. And either way, we are going to impact it. The question is not whether we will stop it or let it continue, but rather whether we will step back and wash our hands of the responsibility for our impacts, or step in, and steward it with thought and care. When we instead look at the question in this light, when we are free from the assumption that distancing ourselves from natural processes necessarily makes them wilder, a different responsibility arises. We are confronted with a responsibility to best advocate for the inhabitants of wilderness that will be affected by us, one way or another. Whether they will be affected is not up for debate. They will.

There is a similar response to Kaye’s earlier claim that “every intervention, however important the resources or uses it seeks to perpetuate, diminishes an area’s wildness, diminishes its freedom to adapt and evolve as it will” (Kaye 2021). However, is an area really adapting and evolving freely when it is already being impacted by our presence? If a wilderness area already is not free from our impacts, then it is perverse for it to be categorically excluded from our stewardship on the basis that that stewardship would undo some supposed separation. If wilderness is going to receive our impacts, then it should also receive our care. This will increasingly come in the form of interventions.

Although elsewhere Kaye claims that “we must move beyond the dualistic vision of humans apart from Nature, as separate entities influencing each other,” he seems to double down on just the opposite (Kaye 2022). What is troubling about the noninterventionist stance is that while its conceptualizations of nature and wildness are supposedly built on a distinction from human intent, it in fact makes sweeping, anthropocentric assumptions about the purpose of wilderness.

Kaye and others have even advocated for various kinds of differentiated, tiered systems of wilderness management to make space for the apparently incompatible management goals of ecological integrity and wildness (Kaye 2021; Kaye 2022). Their proposed “Evolutionary Heritage Lands” would be distinguished from the rest of the National Wilderness Preservation System by remaining wholly free from intervention, even if that means that “the populations of some preferred species will decline” (Kaye 2022, emphasis added). Considering the “aesthetic, psychological, spiritual, and symbolic dimensions” of untrammeled nature, Kaye suggests that “protecting [untrammeled] Nature could then take its place along with biodiversity and ecological integrity as a stewardship goal, rec- ognizing and protecting the values they don’t” (Kaye 2022). If it is true that the Wilderness Act of 1964 marked a shift toward biocentric management, then these proposed tier systems would mark a shift right back. It is troubling that this is seen as an appropriate response to the Anthropocene, when now, more than ever, biodiversity and ecological integrity face unprecedented threats.

Does our right to experience “untouched” wilderness outweigh the right for threatened species to have a protected home? I think most of us would agree it does not. The sad fact is that wilderness today is not what it was – not what it was before industrialized humans took over the world and filled its air with exhaust. Protecting wilderness in times of ecological change requires asking hard questions about what wilderness is, who it is for, and what our role in it will be. Once, mere boundaries were enough. Now, wilderness will require much more active management to protect what lies within those boundaries.

Although we know they were reintroduced, anyone with a pulse is overwhelmed with a deep feeling of wildness – and our role in it – when they hear the mournful, sonorous howl of the wolf. Wildness occurs where ecosys- tems can function as whole. “Wild is where the wolf sings” (Wild Arizona 2023).

Cultivating Wilderness: A Non-Dual Definition of Nature

In his article, “A Plea for a Standard Definition of ‘Natural,’” Tobias Nickel (2021) writes, “In brief, we face the challenge of applying more nuance and thought to the term ‘natural.’” Nickel proposes several options for how “natural” may be redefined in response to the Anthropocene and operationalized in a more standard manner. One of the options he proposes “would be to stress the ecological integrity of an area as a measure of its natural- ness. Under this approach, the science of ecology would be heavily relied upon to assess whether an area is natural according to agreed-upon indices and measurements” (Nickel 2021). If we wish to manage wilderness more biocentrically in times of anthropogenic ecological change, this definition of natural fits the bill. But we must also accept that it will require increased intervention.

When we look at the value of wilderness from a more biocentric point of view, many of our concerns regarding intervention begin to fade away. The assumption that its character depends on our utter absence starts to look self-serving and shallow. Wilderness is habitat. Wilderness is the last best home for the impossibly complex networks of wild processes that our understanding has only begun to scratch the surface of. Although it may require prescribed burns, cut stumps, collared canines, and fish dams, when we preserve these habitats to the best of our informed ability, we allow for a far more natural, wilder place.

Nearly 100 years ago, Leopold took a huge leap in thought when he recognized the critical role that predators play in ecosystems. Now, perhaps what’s needed is a similar leap forward in thought: a recognition of the role that humans play in wilderness. For as long as the woods have been here, humans have been dancing to their music. And although the song may sound different now, we’d better be quick to learn the tune.

When I think of Leopold and Zahniser, and the other founders of the Wilderness Idea, I think not of any particular mandate but rather of their ability to think boldly and differently about our role in natural systems, and the responsibilities we have to them in response to a rapidly changing world. What if we truly took inspiration from them and understood that what they knew then is not what we know today. And what we know today, is not what we will know in the future. As the wild world changes, so should our understanding of it and our responsibilities to it.

Although it may challenge the notion of natural we clung to so dearly, wild places today and in the future are going to have human influence in one form or another. The sad irony is that nature will be left only more marred by the presence of humans without the gentle hand of humanity to guide it on its way. Wild places will be wild because they are well managed. What is needed now is not standing back and standing guard but instead standing up and stepping in.

When I think of the slippery paradox of humans’ role in wilderness today, I am reminded of an old Zen story from Dogen’s Shobogenzo:

As Zen master Pao-ch’e of mount Ma-yu was fanning himself, a monk came up and said, “The nature of the wind is constancy. There is no place it does not reach. Why use a fan?” Pao-ch’e answered, “You only know the nature of the wind is constancy. You haven’t yet grasped the meaning of its reaching every place.” “What is the meaning of its reaching every place?” asked the monk. The master only fanned himself. The monk bowed deeply. (Waddell 2002).

Maybe we aren’t guardians. Maybe we aren’t gardeners either. Maybe we are something else, existing somewhere between the binary. Something like stewards.

LUKE KOENIG is a grassroots organizer and volunteer trail steward living in Silver City, New Mexico; email: lukekoenig123@gmail.com.

Note: The views and opinions expressed in this commentary are strictly the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of his employer.

References

Kaye, R. 2021. Preserving the wildness of wilderness in the Anthropocene. International Journal of Wilderness 27(2): 12–21.

Kaye, R. 2022. Nature in the Anthropocene: What it no longer is, will never again be, and what it can become. International Journal of Wilderness 28(1): 10–17.

Leopold, A. 1949. A Sand County Almanac. Oxford University Press.

McDonald, D., T. McDonald, and L. McAvoy. 2000. Tribal Wilderness Research Needs and Issues in the United States and Canada. RMRS-P-15-VOL-2. Ogden, UT: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service,

Rocky Mountain Research Station.

National Wildlife Federation. 2023. Fremont cottonwood. https://www.nwf.org/Educational-Resources/ Wildlife-Guide/Plants-and-Fungi/Fremont-Cottonwood, accessed March 15, 2023.

Nickel, T. 2021. A plea for a standard definition of “natural” in wilderness stewardship. International Journal of Wilderness 27(3): 18–27.

Scott, D. 2001. Untrammeled, wilderness character, and the challenges of wilderness preservation. Wild Earth (Fall/Winter 2001–2002).

Waddell, N., trans., and M. Abe, trans. 2002. The Heart of Dogen’s Shobogenzo. State University of New York Press.

Wild Arizona. Let the lobo roam the wild. https://www.wildarizona.org/projects/lobo/, accessed March 15, 2023.

Wilderness Act, Public Law 88-577, 16 U.S.C. § 1131–1136 (1964).

World Wildlife Fund. 2020. Recognizing Indigenous people’s land interests is critical for people

and nature. https://www.worldwildlife.org/stories/recognizing-indigenous-peoples-land-interestsiscritical-for- people-and-nature, accessed March 15, 2023.

Read Next

Forgetting Your Anniversary, Again

This year represents the 30th anniversary of the International Journal of Wilderness.

The Trouble with Virtual Wilderness

How the history of the 20th-century wilderness movement might give us different moral guidance as we confront this new technology.

The Road to Wilderness Is Not Paved

The purpose of the research is to determine how accurate and comprehensive the regulations are that are posted on trailhead kiosks.