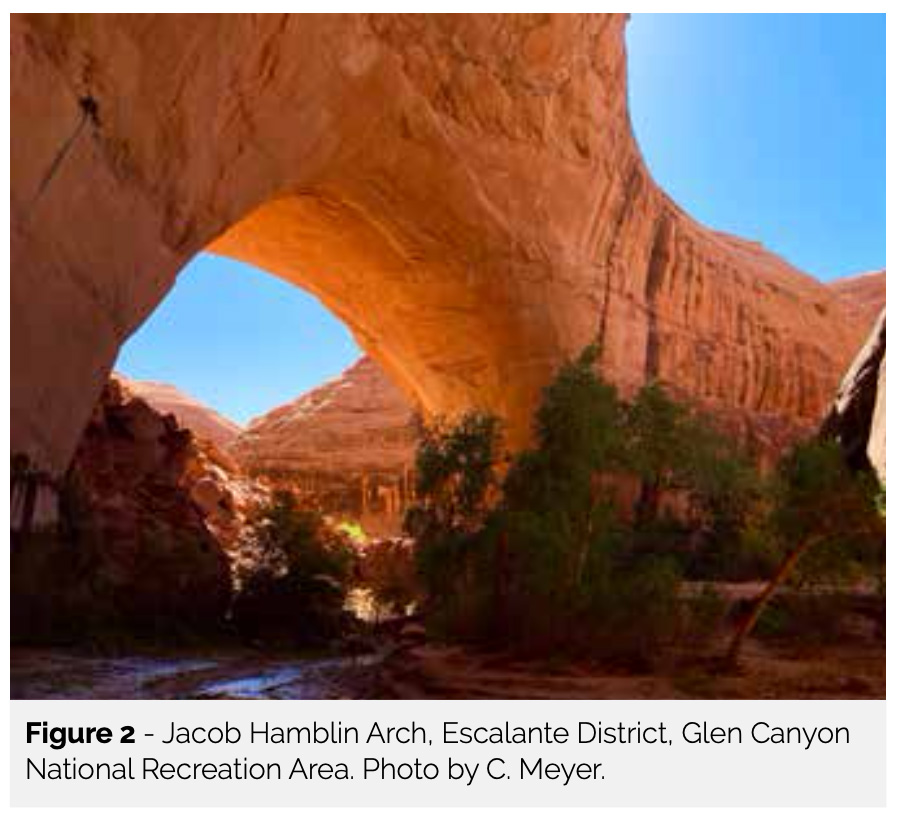

Reflection Canyon and Lake Powell, Escalante District, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. Photo credit: C. Meyer

Examining Opportunities for Solitude or Unconfined Recreation in a Colorado Plateau Wilderness Setting: A Case Study from the Canyons of the Escalante

by CALEB MEYER, WAYNE FREIMUND, ZACH MILLER, ANNA B. MILLER, JEREMY WIMPEY, and B. DERRICK TAFF

Communication + Education

April 2024 | Volume 30, Number 1

Abstract

The Wilderness Act of 1964 mandates that wilderness areas provide outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined recreation. Much deliberation in the wilderness research community has focused on understanding that quality of wilderness, with contem- porary management guidance interpreting the word “or” as “and.” This case study, focusing on an area in the proposed Glen Canyon Wilderness, explores a more ambiguous interpretation of the Wilderness Act through the lens of measures of solitude and unconfined recreation and how they diverge in a remote desert setting with increasing visitation. This research uses quantitative survey data to explore these measures and preferences for management action. Results can help inform wilderness management that considers ambiguity in decision-making while using established frameworks.

The Wilderness Act (P.L. 88-577) contains provisions for management that have been distilled into five qualities of wilderness character by public land management agencies (Landres et al. 2015). These are lands being untrammeled, natural, undeveloped, providing solitude or primitive and unconfined recreation, and “other features of value.” Of these, providing for solitude or a primitive and unconfined recreation is notable in the use of the word “or,” which was not defined in the law (Engebretson and Hall 2019). Interagency guidance by Landres et al. (2015) defined indicators for solitude, primitive, and unconfined recreation, suggesting management for all three qualities is necessary in all wilderness, while also recognizing the difficulties managers face in providing opportunities for wilderness recreation while protecting landscapes. Sixty years of research and guidance later, ambiguity remains as to the other potential interpretation that a wilderness area should provide either solitude or a primitive and unconfined recreation (Engebretson and Hall 2019; Thomsen et al. 2023; Griffin 2017; Cole and Williams 2012). Wilderness management is further complicated by trends and research gaps, including recreation’s relation- ship to degrading ecosystems (Albright et al. 2022; Thomsen et al. 2023), limited research examining changes in visitors and visitation over time (Borrie and McCool 2007), increasing overall visitation and increasing day use (Pierce and Manning 2015; Miller 2022; Abbe and Manning 2007; Cole and Hall 2008), and the limited geographic scope in the body of wilderness research (Rice et al. 2021).

Unconfined recreation, or the freedom from management action influencing visits, has received limited research focus compared with other wilderness character attributes, such as solitude (Cole and Williams 2012; Griffin 2017; Freimund and Cole 2001). Cole and Williams (2012) found few visitors support limiting use and access to protect solitude in their 50-year review of the literature. This is aligned with Pierce and Manning’s (2015) more recent finding of Olympic Wilderness visitors’ opposition to use limits. Meanwhile, philosophical and managerial approaches to the recreation-wilderness relationship often focus on the mandate to provide opportunities for solitude (P.L. 88-577). Research generally uses encounters with other visitors and crowd- ing to measure these opportunities, rather than examining more nuanced characteristics of the wilderness experience framed in naturalness, intragroup interaction, or intergroup conflict (Cole and Williams 2012; Freimund and Cole 2001; Stankey 1973). Furthermore, research suggests negative evaluations of wilderness experience are associated with specified characteristics of encounters (e.g., method of travel, behavioral conflict, camping conditions), rather than frequency or experience of encounters alone (Stankey 1973; Hollenhorst and Jones 2001; Pierce and Manning 2015). Cole and Williams (2012) also found the relationship between use density and overall visitor satisfaction to be weak or nonexistent, and that some visitors reported positive evaluations of encountering others. There is debate regarding the degradation of wilderness character by increasing visitation and on use limits or other factors affect-ing opportunities for unconfined recreation; coalescing around whether visitation density or use limits are more detrimental to overall wilderness character as recreation patterns shift (Cole and Hall 2009; Abbe and Manning 2007; Cole and Williams 2012; Landres et al. 2015).

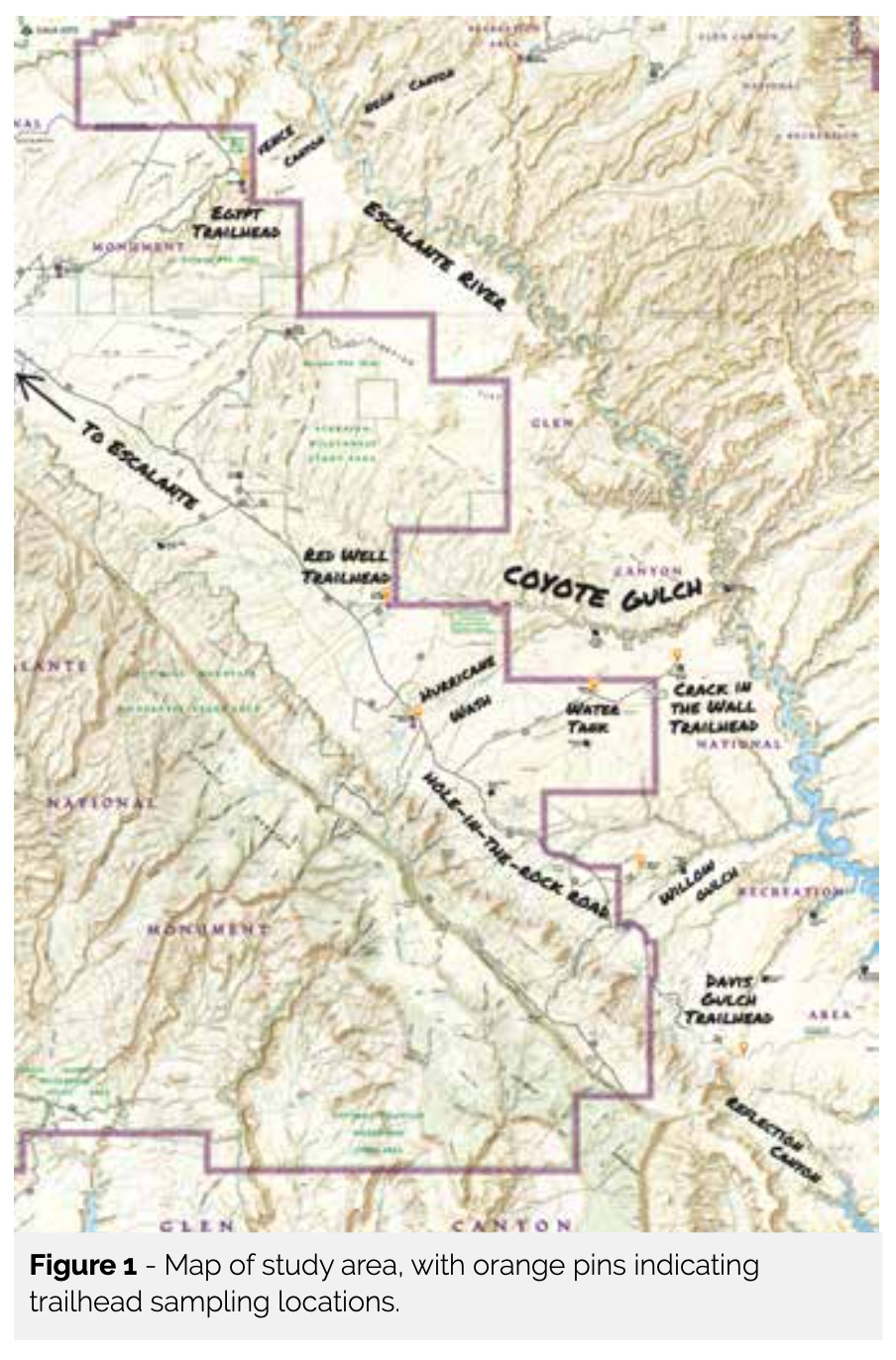

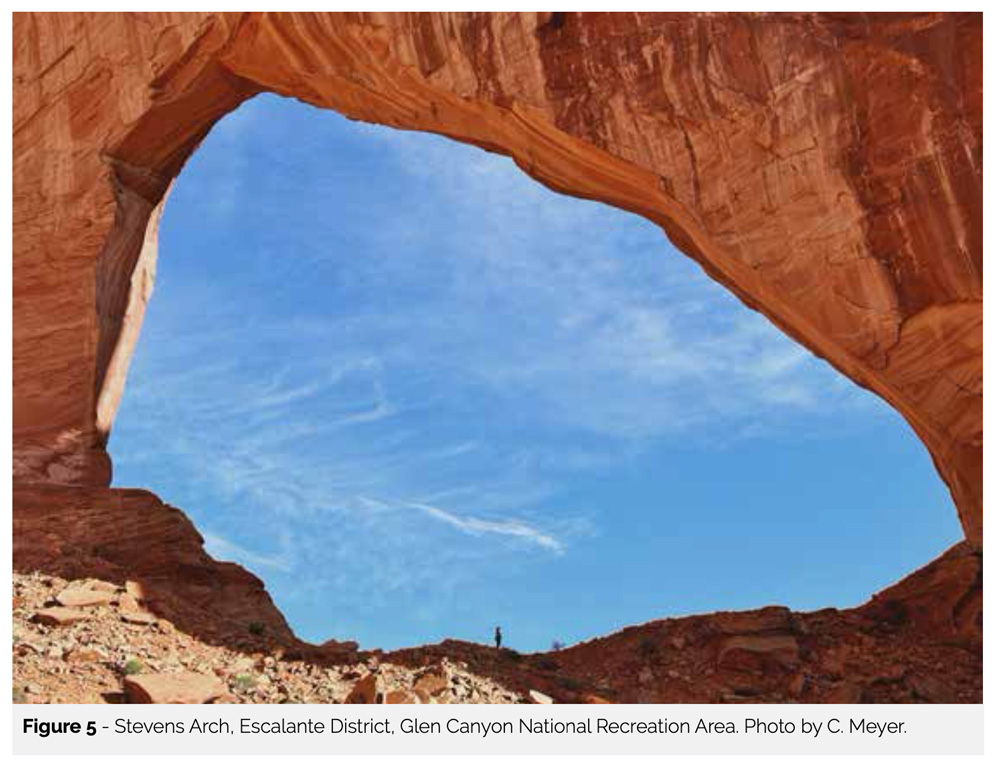

The Glen Canyon National Recreation Area (NRA) in Utah contains the proposed Glen Canyon Wilderness. Proposed wilderness refers to lands with wilderness character forwarded for the consideration of the secretary of the interior to recommend to Congress for designation (Wilderness Connect 2024) and are managed as wilderness. This study focuses on an area of the proposed Glen Canyon Wilderness managed as the Escalante District of the NRA. The Escalante District contains much of the drainage of the Escalante River before it empties into the Colorado River’s Lake Powell reservoir, and it contains high desert sandstone domes, deep canyons, riparian areas surrounding the river corridor, and abundant flora and fauna (Albright et al. 2022). It is remote, with the canyon trailheads sampled being 25 to 50 miles down the rug- ged Hole-in-the-Rock Road from the town of Escalante (Figure 1). Per internal trailhead register data, the Escalante District has seen annual backcountry visitation more than double between 2000 and 2019 as the region becomes a destination aside from Utah’s five national parks, which drive protected area visitation in the Colorado Plateau region of the state (Taff et al. 2019; Smith et al. 2018; Casey 2015). Marion (2014) suggests interactions between recreationists and ecosystems vary across settings, and desert ecosystems are susceptible to impacts and interactions not found in more consistently studied environments due to the presence of delicate soil biocrust, abundant and obvious cultural sites, slow rates of decomposition, or specific low impact regulations (Colleony, Geisler, and Schwartz 2021; Taff et al. 2019). The Escalante District is experiencing ecosystem degradation due to recreation and other factors (Albright et al. 2022).

Qualitative research in adjacent areas of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument suggests visitors are also being displaced to the subregion by conditions in heavily visited parks such as Zion and Bryce Canyon (Taff et al. 2019). This possible displacement necessitates consideration of the region as an interconnected system of public lands covering the Colorado Plateau. In such regions, actions or conditions in one unit can have wide-reaching, systemic effects, such as a congested national park nudging visitors to a nearby wilderness setting (McCool and Cole 2001; McCool, Freimund, and Breen 2015; Taff et al. 2019). This case study examines experiential conditions and management preferences related to solitude and unconfined recreation in a context where managers might prioritize one wilderness quality over another, considering the word “or” in the Wilderness Act. Specifically, this juxtaposition is explored through experiences and preferences of back- packers in the Escalante District as recreation use in the area increases and further management actions are considered.

Methods

Escalante District visitors were surveyed in 2021 to provide data informing the National Park Service’s backcountry planning process for the area. The survey was developed and administered by personnel at Utah State University in consultation with park staff and informed by prior research on nearby Wilderness Study Areas (Taff et al. 2019). The instrument measured experiential conditions, evaluation of conditions by visitors, support for management action, information sources, self-reported Leave No Trace behavior, trip characteristics, and basic demographic information.

The survey was administered at seven trailheads in the Escalante District during spring and fall 2021. Each sampling period incorporated 12 days of sampling spread across trailheads and daylight hours to uniformly capture visitor use. Every visitor was approached as they exited a trail and asked to participate unless another survey was in progress. Within-group randomization occurred by asking parties who had the closest birthday to the present and asking that person to be the participant. Only one member of each party was surveyed. Precautions related to the COVID-19 pandemic included social distancing, masking, and sanitation of equipment after use.

Surveys were administered using iPads and the Qualtrics Survey Platform. Descriptive statistical analyses were performed using IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), and data management practices took all measures to protect human subjects and safeguard data in accordance with instrument approval by Utah State University’s Institutional Review Board (protocol #10768) and the US Federal Office of Management and Budget (Control No. 1024-0224). All respondents were visitors of the proposed Glen Canyon Wilder- ness in the Escalante District of Glen Canyon NRA. Respondents who identified as back- packers were isolated in the larger sample by filtering responses based on self-identification of “primary activity” during their recreation visit. Backpackers were isolated from a larger sample of recreationists in this case study as potential management scenarios discussed refer more frequently to overnight visitors. For this purpose, 97 day-visitor responses were removed with an overall study response rate of 98%.

Results

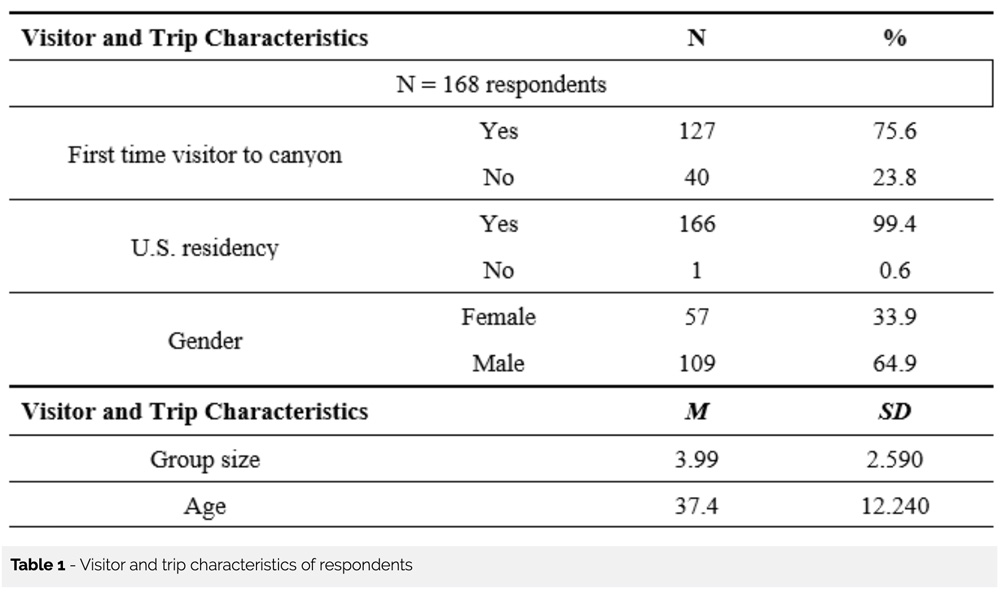

Findings and analyses are based on n = 168 completed surveys by overnight visitors and a subsample response rate of 100%. Most (75.6%) respondents were first-time visitors to the site they were recreating in (Table 1). All but one respondent were US residents (this proportion may be lower than other years due to the COVID-19 pandemic’s presence during sampling). Average group size was 3.99, and average age of participants was 37.4 years old. Most respondents were male (64.9%).

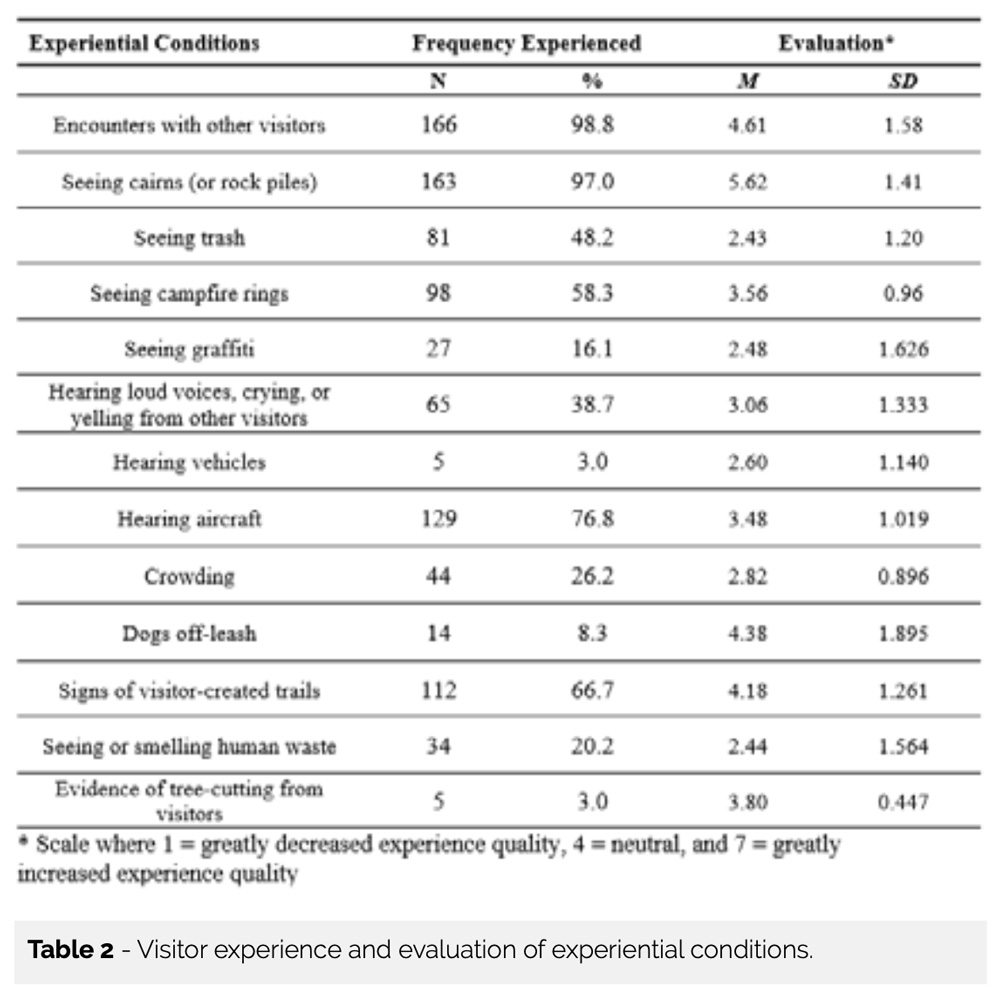

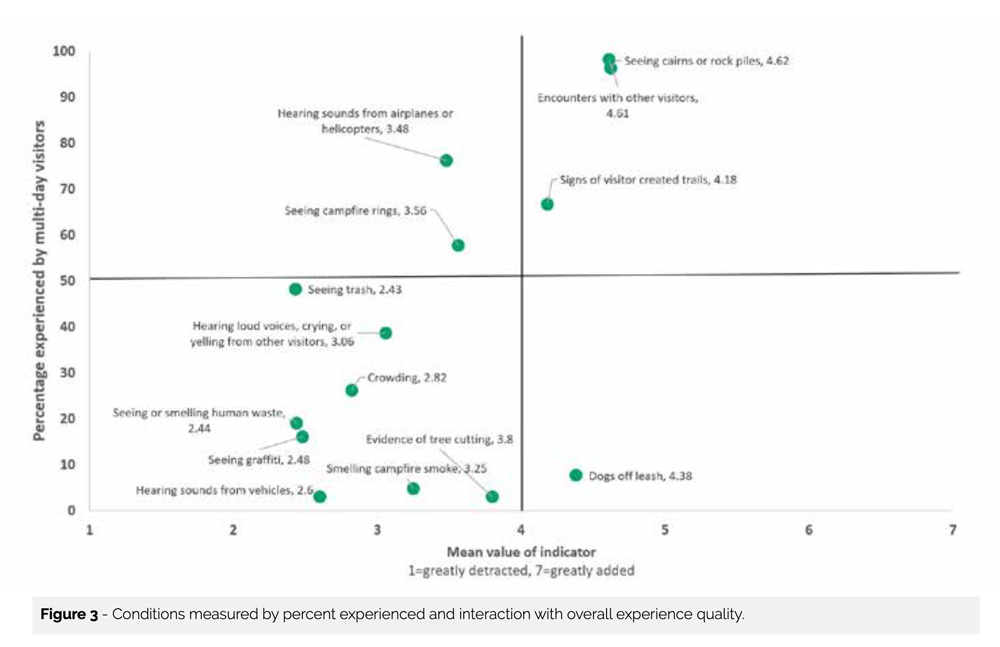

Fourteen conditions were measured both for the frequency they were experienced and their interaction with visitors’ experiences on a scale where 1 = greatly detracted and 7 = greatly added to the overall experience, and 4 = neutral (Table 2). One condition, “smelling campfire smoke” was removed from analysis due to sample size. The conditions experienced by most visitors and rated highest were “encounters with other visitors” (98.8%; M = 4.61), “seeing cairns (or rock piles)” (97.0%; M = 5.62) and “signs of visitor-created trails” (66.7%; M = 4.18). Conditions experienced by a substantial minority of visitors and rated lowest were “hearing sounds from airplanes or helicopters” (76.8%; M = 3.48), “seeing campfire rings” (58.3%; M = 3.56), “seeing trash” (48.2%; M = 2.43), “hearing loud voices, crying, or yelling from other visitors” (38.7%; M = 3.06), and “crowding” (26.2%; M = 2.82) (Figure 3).

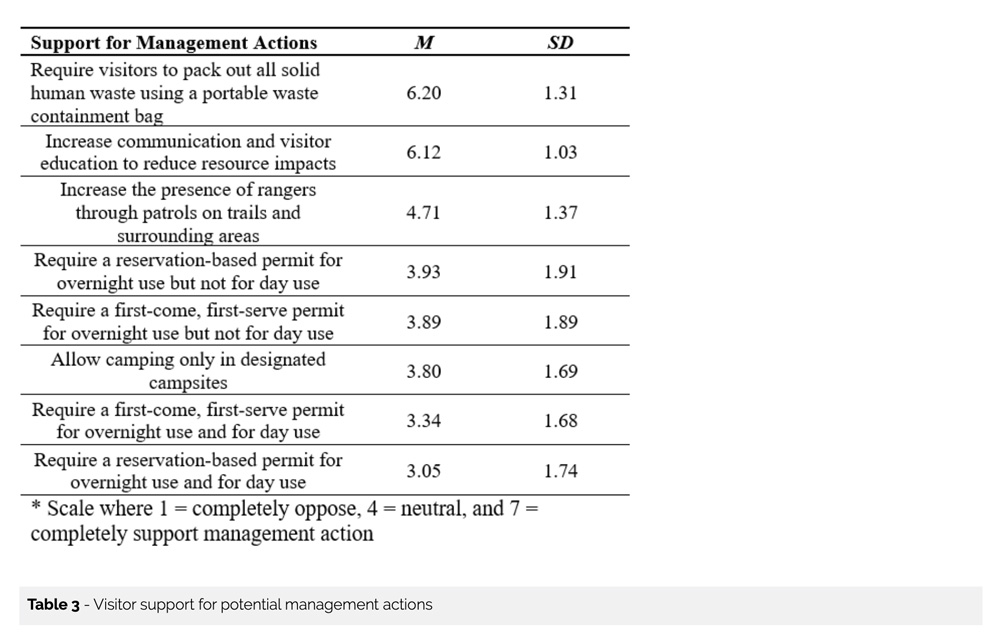

Eight potential management scenarios were explored from the visitor perspective by asking the level to which visitors opposed or supported the action (Table 3). Five potential actions measured evaluation of limits to an unconfined type of recreation per the inter- agency definition (Landres et al. 2015). All five of these scenarios relating to permits or designated camping were opposed by respondents. Three other scenarios were supported by respondents with “requiring visitors to pack out all solid human waste using a portable waste containment bag” being the most supported scenario (M = 6.20). This is already an implemented action for Escalante District visitors.

Discussion

There has been a great dependence on measuring encounters in wilderness research, with the assumption that they indicate crowding or loss of solitude (Freimund and Cole 2001; Stankey 1973). In this study, encounters were widely reported and did not indicate these conditions. Far fewer visitors reported experiencing crowding. Visitation is rising in the Escalante District, and nearly all visitors encountered others during their visit. Most visitors reported encounters adding to the quality of their experience. Furthermore, visitors opposed the management actions evaluated that would curtail spontaneity and freedom of movement in the area.

The Wilderness Act specifically includes the word “or” concerning managing for solitude, or primitive, and unconfined recreation (P.L. 88-577; Griffin 2017; Engebretson and Hall 2019). In Landres et al. (2015), interagency management guidance suggests these three provisions are taken together, effectively swapping the word “or” for “and” in the legislation. By rejecting vague language that allows for adaptive and targeted management action, decades of interpretation have left managers in a predicament wherein choices need to be made that ignore human adaptability, or evaluations of wilderness visits that show use density having little effect on experience quality (Cole and Williams 2012). Wilderness recreation research from the past decade has yielded findings that continue to build on Stankey’s (1973) and Freimund and Cole’s (2001) concerns with approaching wilderness experience questions using solitude and its simple measure of encounters, whether as a rate or stand-alone experience. Pierce and Manning’s (2015) study of Olympic Wilder- ness visitors found opposition to use limits to reduce crowding. A 2014 study on the low-use Wenaha Wild and Scenic River found, as in the Escalante District, that encountering other visitors in a relatively low-use density area increased enjoyment (Burns, Popham, and Smaldone 2018).

Respondents in this case study were largely first-time visitors, but studies of returning wilderness visitors (Borrie and McCool 2007) also find majority opposition to use limits on unconfined recreation. Across six decades of research, results show visitors, first time and returning, would rather see other people than be limited in their recreation to protect solitude (Cole and Williams 2012). Moreover, they may enjoy seeing other people as they do in the Escalante District (Burns et al. 2018). This case study’s results concerning experiential conditions and management preferences suggest visitor preference in the Escalante District centers around self-sufficiency, with other human encounters being largely positive. This preference for unconfined recreation over other qualities may also stem from visitors potentially being displaced from high-use national park settings, further emphasizing the importance of places such as the Escalante District, which contain exceptional natural features without national park visitation density (Taff et al. 2019). If following the philosophical view of some previous researchers that wilderness experience can be “motivated by the not very well-defined goal of acquiring stories that ultimately enrich one’s life” (Patterson, Watson, Williams, and Roggenbuck 1998, p. 423), visitors to the Escalante District aim to acquire stories where they may go and do as they please, perhaps alongside others, and they support minimal low-impact regulations to preserve this experience, such as packing out their waste.

These findings, and others from the past decade and beyond (Pierce and Manning 2015; Taff et al. 2019; Burns et al. 2018; Cole and Williams 2012) provide an opportunity to accept the ambiguity contained in the legislation and demonstrate that there are clear differences in the way an area is managed depending on whether the word “or” is taken literally. The word “or” provides managers with two distinct options for the management of wilderness areas. In this approach, a hypothetical wilder- ness exists where encounter rates are high, where solitude may be experienced despite having little to do with other people (Cole and Williams 2012), and where visitors are free from tangible governmental interference.

This case study examines the complexity of just one (as defined) quality of wilderness character. While some questions examined in this research regarding potential management scenarios address the quality of naturalness (referring to ecological systems that are substantially free from the effects of modern civilization [Landres et al. 2015]), the questions regarding unconfined recreation were not framed in protecting naturalness. This is notable in Cole and Williams’s (2012) finding that solitude is less critical to a high-quality wilderness experience than scenic, natural-appearing, and undeveloped landscapes. The Escalante District is currently experiencing ecological degradation from numerous factors, including recreation (Albright et al. 2022), and impacts from tourism have been occurring there for at least several decades (Carey 1982). Considering naturalness, inherent to outstanding opportunities for all aspects of wilderness recreation, and to the general construct of wilderness itself (Thomsen et al. 2022) may clarify managerial approaches in providing for solitude or unconfined recreation, with naturalness being the limiting factor in management treatments.

The recent Interagency Visitor Use Management Framework (IVUMF) (IVUMC 2016) can guide the minutiae of wilderness management that adheres to the Wilderness Act of 1964. Using the IVUMF can establish management objectives built around limiting factors identified in collaboration between recreation managers, ecologists and specialists, and visitors to safeguard the places the Wilderness Act was designed to protect, and the types of experiences it was designed to promote.

Following through on implementing, monitoring, evaluating, and adjusting management strategies (IVUMC 2016) can further provide opportunities for managers to adapt, on smaller spatial scales, to ecological function- ing needs or visitor responses, such as those explored in this case study that highlight areas where vague legislative intent collides with creative potential. Where naturalness is hypothetically a limiting factor in an Escalante District faced with numerous biological stress- ors such as increasing recreation, managers might identify areas where use should be limited to align with the Wilderness Act’s naturalness requirement and others where unconfined recreation could yet coexist with the natural order.

That zonal example may bypass consideration of solitude, but the findings presented in this case study affirm research’s inadequacy in understanding and helping manage for solitude (Stankey 1973; Freimund and Cole 2001; Burns et al. 2018). Hollenhorst and Jones (2001) approach solitude from American Transcendentalism and the relationship between nature and industrial society central to the Wilderness Act. They conclude that solitude experiences imply freedom from social influences and constraints and psychologically equate solitude experiences, as distilled through the philosophical underpinnings of the legislation, with the freedom found in unconfined recreation (Hollenhorst and Jones 2001).

This case study only uses notably outdated measures to discuss solitude through data. Much effort has been made in dissecting the intent of the Wilderness Act (Engebretson and Hall 2019), and while this research examines that discussion again through a remote wilderness setting where social measures and unconfined recreation measures are convergent, it gets no further in addressing the great challenge research and management faces in respecting visitors’ need for freedom to cultivate the inner world of the self while also protecting the ecological values of wilderness (Hollenhorst and Jones 2001).

Limitation

Study of the Wilderness Act finds broad interpretation of the constructs behind primitive and unconfined types of recreation (Engebretson and Hall 2019; Griffin 2017). This study focused only on unconfined recreation. The examination of visitors’ preferences for management action affecting ease of travel does not capture the full range of constructs behind that wilderness character quality (Landres et al. 2015), nor does this study address the inadequacies of using encounters or crowding to discuss solitude. An example not explored in this study is the preference of some wilderness visitors for levels of infra- structure development beyond interpretations of “primitive” that could add further refinement to this discussion (Landres et al. 2015; Cole and Hall 2009; Pierce and& Manning 2015; Engebretson and Hall 2019). This case study also did not directly frame questions in the quality of naturalness, which is inherent to discussions of solitude and unconfined recreation (Cole and Williams 2012). This research did spawn unanswered questions about how safety may factor into remote wilderness recreation. Conditions experienced by most visitors and evaluated positively all contained an element indicative of human presence in a remote area (encountering others, seeing cairns, and seeing visitor-created trails). Some research has examined the role of technology on safety in wilderness (Pope and Martin 2011), but respondents’ evaluations of these conditions necessitate future research following how the presence of others in an area may enhance wilderness experience related to a sense of safety and to the quality of primitive recreation.

Implications for Future Research

The Escalante District does not see the visitation of some heavily used and studied wilderness areas examined in prior research. Despite bringing this conversation into new regions and a high-desert ecosystem, this research focused on a single wilderness setting. These lines of thought would benefit from further study in other desert settings where sensitive resources may require unique, low-impact regulations (Rice et al. 2021). Future research on visitor use or wilderness in the desert ecosystems on the Colorado Plateau should also aim to capture the region as an interconnected system, wherein visitors may be visiting a number of protected area units across agencies and may be displaced by conditions or management actions in other destinations (Taff et al. 2019; McCool and Cole 2001). Managerial collaboration, and inter- agency tools such as the IVUMF (IVUMC 2016) can help plan across designations to provide outstanding recreation opportunities through diverse and interconnected settings and aid in safeguarding the unique values for which individual protected areas are designated (McCool and Cole 2001).

Future research should also approach questions on smaller spatial scales. Understanding where visitors are experiencing conditions within a recreation system could contribute to developing the most targeted and inclusive management strategies available (Borrie and Roggenbuck 2001). In this case study, the lingering question on encounters’ (positively evaluated) relationship to crowding (negatively evaluated) could be explored through determining if crowding was primarily experienced in specific areas. Next steps along a Management-by-Objectives Framework such as the IVUMF (IVUMC 2016; Miller et al. 2019) suggest future research should also focus on the establishment of thresholds that account for the sensitivity of ecosystems to increased use in the Escalante District and elsewhere (Cole and Stewart 2002; Miller et al. 2019). Longitudinal studies of changes in visitors and visitor use are limited (Borrie and McCool 2007). Wilderness research often treats visits to that setting as distinct events (Cole and Williams 2012), despite findings that wilderness experiences, and derived values, are multiphasic and temporally diffused beyond the physical visit (Cole and Williams 2012; Patterson et al. 1998; Borrie and Roggenbuck 2001). Findings of this study, such as positive evaluations of encounters and opposition to permitting, are aligned with Borrie and McCool’s (2007) longitudinal results on these topics from the Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex. A 2007 survey of managers suggests wilderness visitation is changing (Abbe and Manning 2007) and in some areas, it is (Borrie and McCool 2007), but wilderness areas are unique in their specific values (Landres et al. 2015). Monitoring those values alongside the universal qualities of wilderness character, and understanding changes to the visitor and visitor experience in a specific wilderness setting and its surrounding systems, can satisfy the legislative and systemic requirements of wilderness (IVUMC 2016; Landres et al. 2015) and ensure management approaches are aligned with shifts in visitation and visitor preference (Pierce and Manning 2015; Selin et al. 2020; Mockrin et al. 2018).

Conclusion

The Escalante District provides a lens into wilderness topics such as solitude and unconfined recreation. Understanding how visitors experience conditions, such as encountering others, and what their preferences are for management actions (e.g., permit systems or designating camp- ing), can aid wilderness managers in providing experiences commensurate with the preferences and motivations of current and future generations of backcountry recreationists. The findings of this study shed light on how some provisions of the Wilderness Act exist in a remote, desert wilderness setting on the Colorado Plateau, where visitors must expend some effort simply to reach it. While outstanding opportunities for solitude, as inadequately measured through encounters or crowding, may be more important in other wilderness areas, the constructs most used to measure those opportunities are not held as highly among visitors in this remote wilderness setting. Instead, Escalante District visitors appear to value the constructs behind unconfined rec- reation more so even as visitation increases. Setting aside the wrong measures and philosophical discussion, the community of wilderness research and management has opportunity to use interagency-developed approaches to account for, and perhaps to embrace, the ambiguity in the legislation to better align with what we do understand about the underpinnings of wilderness qualities.

CALEB MEYER is an outdoor recreation planner with the Bureau of Land Management’s Monticello Field Office At the time of this study, he was a graduate researcher in Utah State University’s Department of Environment and Society; cmeyer@blm.gov.

WAYNE FREIMUND is a professor of recreation resource management at Utah State University.

ZACH MILLER is a social scientist with the Bureau of Land Management’s National Operations Center; zacharymiller@blm.gov.

ANNA B. MILLER is an assistant professor of recreation resource management and the environment in Utah State University’s Department of Environment and Society.

JEREMY WIMPEY is the principal researchers for Applied Trails Research.

B. DERRICK TAFF is an associate professor at Penn State University’s Department of Recreation, Park and Tourism Management, and the science advisor for the Leave No Trace organization; bdt3@psu.edu.

The views expressed in this article are the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the opinions or policy of the National Park Service or Bureau of Land Management.

References

Abbe, J. D., and R. E. Manning. 2007. Wilderness day use: Patterns, impacts and management. International Journal of Wilderness 13(2): 21–25.

Albright, J., K. Struthers, L. Baril, J. Spence, M. Brunson, and K. Hyde. 2022. Natural

Resource Conditions at Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. Natural Resource Report NPS/SCPN/NRR – 2022/2374.

Borrie, W. T., and S. F. McCool. 2007. Describing change in visitors and visits to the “Bob.” International Journal of Wilderness 13(3): 28–33.

Borrie, W. T., and J. W. Roggenbuck. 2001. The dynamic, emergent, and multi-phasic nature of on-site wilderness experience. Journal of Leisure Research 33(2): 202–228.

Burns, R. C., A. R. Popham, and D. Smaldone. 2018. Examining satisfaction and crowding in a remote, low use wilderness setting: The Wenaha Wild and Scenic River case study. International Journal of Wilderness 24(3): 40–53.

Carey, M. B. 1982. Proposed management options for the amelioration of recreational impacts on Coyote Gulch, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Kane County, Utah. Master’s thesis, Duke University.

Casey, T. 2015. Recreation Experience Baseline Study Report for Grand Staircase- Escalante National Monument. Natural Resource Center, Colorado Mesa University.

Cole, D. N., and T. E. Hall. 2008. Wilderness Visitors, Experiences, and Management Preferences: How They Vary with Use Level and Length of Stay. (Research Paper RMRS-RP-71). USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station.

Cole, D. N., and T. E. Hall. 2009. Perceived effects of setting attributes on visitor experiences in wilderness: Variation with situational context and visitor characteristics. Environmental Management 44: 24–36.

Cole, D. N., and W. P Stewart. 2002. Variability of user-based evaluative standards for backcountry encounters. Leisure Sciences 24: 313–324.

Cole, D. N., and D. R. Williams. 2012. Wilderness visitor experiences: A Review of 50 years of research. In Wilderness Visitor Experiences: Progress in Research and Management, April 2011, Missoula, Montana. USDA Forest Service, Proceedings (RMRS-P-66).

Colleony, A., G. Geisler, and A. Schwartz. 2021. Exploring biodiversity and users of campsites in desert nature reserves to balance between social values and ecological impacts. Science of the Total Environment 770.

Engebretson, J. M., and T. E. Hall. 2019. The historical meaning of “outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation” in the Wilderness Act of 1964. International Journal of Wilderness 25(2): 10–31.

Freimund, W. A., and D. N. Cole. 2001. Use density, visitor experience, and limiting recreational use in wilderness: Progress to date and research needs. In Visitor Use Density and Wilderness Experience: Proceedings, June 2000, Missoula, Montana. USDA Forest Service, Proceedings (RMRS-P-20), 56–61.

Griffin, C. B. 2017. Managing unconfined recreation in wilderness. International Journal of Wilderness 23(1): 13–17.

Hollenhorst, S. J., and C. D. Jones. 2001. Wilderness solitude: Beyond the social-spatial perspective. In Visitor Use Density and Wilderness Experience: Proceedings, June 2000, Missoula, Montana. USDA Forest Service, Proceedings (RMRS-P-20), 56– 61.

Interagency Visitor Use Management Council. 2016. The Interagency Visitor Use Management Framework. https://visitorusemanagement.nps.gov/VUM/Framework.

Landres, P., C. Barns, S. Boutcher, T. Devine, P. Dratch, A. Lindholm, L. Merigliano, N. Roeper, and E. Simpson. 2015. Keeping It Wild 2: An Updated Interagency Strategy to Monitor Trends in Wilderness Character across the National Wilderness Preservation System. October 2015, Fort Collins, Colorado. USDA Forest Service, General Technical Report (RMRS-GTR-340).

Marion, J. L. 2014. Leave No Trace in the Outdoors. Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics. Stackpole Books.

McCool, S. F., and D. N. Cole. 2001. Thinking and acting regionally: Toward better decisions about appropriate conditions, standards, and restrictions on recreation use. The George Wright Forum 18(3): 85–98.

McCool, S. F., W. A. Freimund, and C. Breen. 2015. Benefiting from complexity thinking. In Protected Area Governance and Management (pp. 291–326). ANU Press.

Miller, Z. D. 2022. What is visitor use management? Identifying functional and normative postulates of an interdisciplinary field. International Journal of Wilderness 28(1): 32–44.

Miller, Z. D., W. L. Rice, B. D. Taff, and P. Newman. 2019. Concepts for understanding the visitor experience in sustainable tourism. In A Research Agenda for Sustainable Tourism (pp. 53–69). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Mockrin, M. H., S. I. Stewart, M. S. Matonis, K. M. Johnson, R. B. Hammer, and V. C. Radeloff. 2018. Sprawling and diverse: The changing U.S. population and implications for public lands in the 21st century. Journal of Environmental Management 215: 153–165.

Patterson, M. E., A. E. Watson, D. R. Williams, and J. R. Roggenbuck. 1998. An hermeneutic approach to studying the nature of wilderness experiences. Journal of Leisure Research 30(4): 423–452.

Pierce, W. V., and R. E. Manning. 2015. Day and overnight visitors to the Olympic Wilderness. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism 12: 14–24.

Pope, K., and S. R. Martin. 2011. Visitor perceptions of technology, risk, and rescue in wilderness. International Journal of Wilderness 17(2): 19–26.

Rice, W. L., C. A. Armatas, J. M. Thomsen, and J. R. Rushing. 2021. Distribution of visitor use management research in US wilderness from 2000 to 2020: A scoping review. International Journal of Wilderness 27(3): 46–61.

Selin, S., L. K. Cerveny, D. J. Blahna, and A. B. Miller. 2020. Igniting Research for Outdoor Recreation: Linking Science, Policy, and Action, USDA Forest Service. General Technical Report, Pacific Northwest Research Station, USDA Forest Service (PNW-GTR-987).

Smith, J. W., E. Wilkins, R. Gayle, and C. C. Lamborn. 2018. Climate and visitation to Utah’s “Mighty 5” national parks. Tourism Geographies 20(2): 250–272.

Stankey, G. H. 1973. Visitor Perception of Wilderness Recreation Carrying Capacity. (Research Paper, INT-142). USDA Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station.

Taff, B. D., J. Wimpey, J. Marion, J. Arredondo, F. Meadema, F. Schwartz, B. Lawhon, and C. Dems. 2019. Informing planning and management through visitor experiences in Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. International Journal of Wilderness 25(2): 5–57.

Thomsen, J. M., W. L. Rice, J. F. Rushing, and C. A. Amatas. 2023. U.S. wilderness in the 21st century: A scoping review of wilderness visitor use management research from 2000 to 2020. Journal of Leisure Research 54(1): 3–25.

US Public Law 88-577. 1964. The Wilderness Act.

Wilderness Connect. 2024. National Park Service wilderness recommendation process. https://wilderness.net/ practitioners/agency-resources/national-park- service/designate-nps.php.

Read Next

Forgetting Your Anniversary, Again

This year represents the 30th anniversary of the International Journal of Wilderness.

The Trouble with Virtual Wilderness

How the history of the 20th-century wilderness movement might give us different moral guidance as we confront this new technology.

Revisiting Human’s Role in Wilderness

The question we must ask ourselves today is familiar: Are we guardians, or are we gardeners?