International Perspectives

August 2016 | Volume 22, Number 2

BY FRANS SCHEPERS and PAUL JEPSON

Rewilding is a powerful new term in conservation. This may be because it combines a sense of passion and feeling for wilder nature with advances in ecological science. In Europe, rewilding is gathering momentum as a young and vibrant movement of conservationists and citizens seeking a counterweight to our increasingly regulated lives, society, landscapes, and nature. It signifies a desire to rediscover the values of freedom, spontaneity, resilience, and wonder embodied in Europe’s natural heritage, and to revitalize conservation as a positive, future-oriented force. Rewilding is now widely reported in the European media. It is exciting, engaging, and challenging, and it promotes healthy debate and deliberation on what is natural and the natures we collectively wish to conserve and shape. In the context of Europe’s dynamic multicultural societies and landscapes, a distinct approach to rewild-ing is unfolding – one that is shaped by our conservation heritage but that resets expectations of what is possible in European biodiversity conservation policy. In this article, we present the latest thinking and developments on rewilding in Europe, with a focus on the efforts of Rewilding Europe and its many partners across the continent.

Rewilding in the European Context

In Europe, just as in the United States, rewilding is developing in relation to the cultural and institutional context of conservation. In the United States this context is influenced by the wilderness ethic and the ability to conserve functional ecosystems at a large scale. In Europe there are some key differences that affect the development of rewilding. First, European ideas of the wild are influenced by long traditions of scientific, recreational, and cultural engagement with rugged landscapes. National parks in regions such as the Alps and Pyrenees are much more lived in and more developed in terms of recreational infrastructure than their US counterparts. This creates an opportunity and indeed an imperative for larger rewilding projects to link the restoration of natural processes with the modern economy and society. Second, there has been an interesting resurgence of iconic wildlife species in Europe over the last 40 to 50 years, both in mammals and birds (Deinet et al. 2013). Wolf populations are rebuilding themselves in regions of Europe due to legal protection and processes of rural depopulation rather than active management. At the same time in large parts of the continent, biodiversity is still decreasing due to the ongoing intensification of agriculture, forestry, and fisheries. Thus, the comeback of large carnivores is remarkable and shows Europe has found ways of coexistence with such species, albeit not without challenges (Chapron et al. 2014). Finally, the baseline for conservation policy in many European nations has been preindustrial agriculture, which requires the protection and maintenance of wildlife-rich patches of cultural landscapes through active scientific management. This conservation approach, which has been compared to restoring a painting that then needs curating, is at odds with the process-oriented ethos of rewilding and the uncertain ecological and conservation dynamics this entails.

In the context of Europe, rewilding is not synonymous with wilderness. It is about moving up the scale of wildness within the constraints of what is possible. Rewilding is seen as a process rather than a state, it is about giving ecosystems a functional “upgrade,” whatever their nature, scale, or location. On a hypothetical rewilding scale of 1–10, wilderness areas would already be at 9–10 and restricting rewilding to this upper end would limit both its geographical scope and transformative potential.

A Working Definition for European Rewilding

The scientific literature presents a number of definitions of rewilding, but none fully captures the specifics of Europe’s history, culture, landscape conditions, and the element of coexistence, which are so relevant for conservation in Europe. In response, Rewilding Europe published the following “working definition” of rewilding in 2015 and is encouraging other organizations and initiatives to adopt it:

Rewilding ensures that natural processes and wild species play a much more prominent role in the land- and seascapes, meaning that after initial support, nature is allowed to take more care of itself. Rewilding helps landscapes become wilder, whilst also providing opportunities for modern society to reconnect with such wilder places for the benefit of all life.

As such, rewilding is a multi-faceted concept with three broad dimensions that interact with each other: (1) restoring and giving space to natural processes, (2) reconnecting wild(er) nature with the modern economy, and (3) responding to and shaping cosmopolitan perceptions of nature conservation among Euro-pean society. As such, rewilding in a European context is much broader than “species reintroductions.” The following principles are coming to characterize and guide rewilding in Europe as a distinct approach to conservation.

• Restoring natural processes and ecological dynamics, including both those that are abiotic, such as river flows, and those that are biotic, such as the ecological web and food chain through reassembling lost guilds of animals in dynamic landscapes.

• A gradated and situated approach, where the goal is to move up in the scale of wildness within the constraints of what is possible, and interacting with local cultural identities.

• Taking inspiration from the past but not replicating it by developing new natural heritage and values that evoke the past but shape the future – with the point of reference in the future, not in the past.

• Creating self-sustaining, robust eco-systems (including reconnecting habitats and species populations within wider landscapes) that provide resilience to external threats and pressures, including the impact of climate change.

• Working toward the ideal of passive management, where once restored, humans step back and allow dynamic natural processes to shape conservation outcomes.

• Creating new natural assets that connect with modern society and economy and promote innovation and enterprise in and around natural areas, leading to new nature-inspired economies that conversely also contribute to rewilding.

• Reconnecting policy with a grass-roots conservation sentiment and a recognition that conservation is a culturally dynamic as well as a scientific and technical pursuit (Jepson and Schepers 2016).

A Short History of Rewilding Europe

A prominent factor in the emergence of European rewilding is the rise of functional ecology, which has exposed the extent to which in Europe we have come to accept degraded ecosystems and introduced a new focus on restoring ecological functions. Also, large-scale land abandonment and a substantial wildlife revival in regions of Europe (Deinet et al. 2013) were identified as a historic opportunity for nature conservation and to build new rural economies on wild values. As a result, the number of popular articles and books that connect rewilding with public demand for more exciting engagements with nature has increased rapidly during the last few years. In 2008, conservationists in the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and Sweden began to explore the con-servation opportunities presented by these trends. The group was particu-larly interested in engaging with the dynamics of large-scale land abandon-ment of rural areas in Europe. They were concerned that spontaneous reforestation and declines in grazing associated with land abandonment would result in a loss of the rich bio-diversity, and that the exodus of skills, experience, and energy from rural areas would undermine opportunities to “steer” these landscapes towards a rewilded future where restored ecological systems supported new nature-based economies. This group was the founding inspiration for Rewilding Europe.

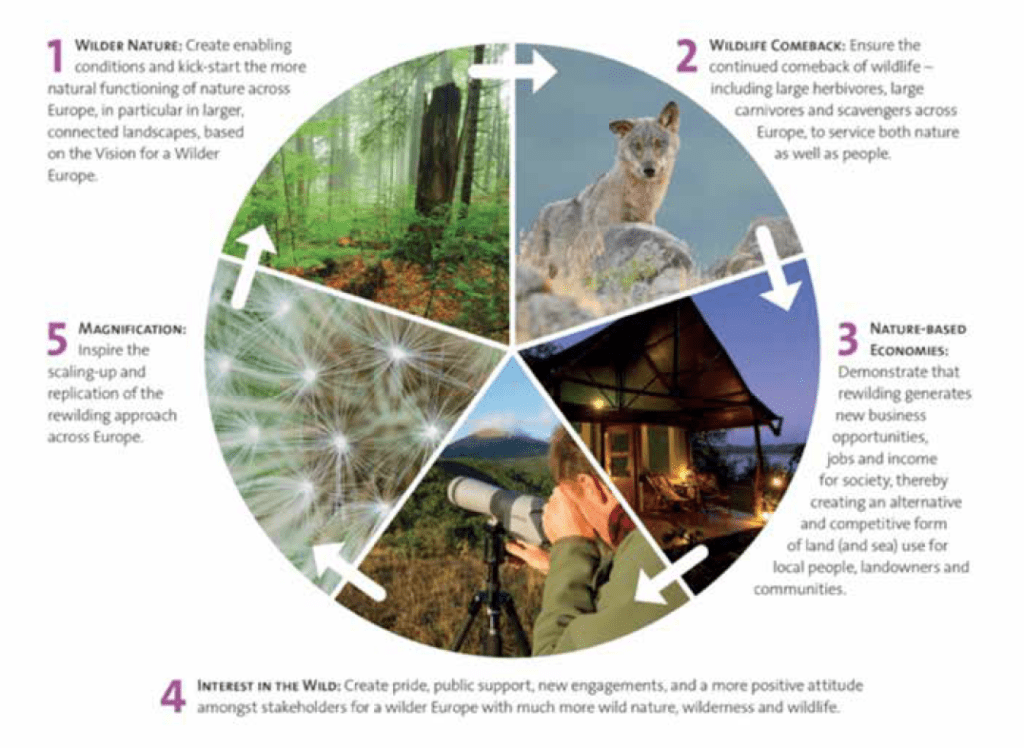

They set an agenda by asking if we could develop and launch a new but complementary vision and approach to conservation in Europe that would address such opportunities and challenges, and if we could pioneer and develop these new ideas in practice in areas across Europe, providing new perspectives for both nature and people. After three years of preparations and fund-raising, Rewilding Europe was created in 2011 with support from the World Wide Fund for Nature (Netherlands), Wild Wonders of Europe, Conservation Capital, and ARK Nature. It pursues a vision in which “wild nature is recognised as an important and inherent aspect of Europe’s natural and cultural heritage and an essential element of a modern, prosperous, and healthy Euro-pean society in the 21st century.” Rewilding Europe has developed an ambitious strategy to put this vision into reality through five 10-year objectives (Figure 1).

These objectives are being pursued by creating 10 rewilding areas in different geographical regions and in different socioeconomic settings across Europe. Areas have been chosen where rewilding is possible at a scale of least 100,000 hectares (247,105 acres) within a wider landscape setting. By early 2016, nine of these are operational and are run and owned by local partner organizations that receive technical, financial, and promotional support from the Rewilding Europe central team. Beyond developing these 10 rewilding areas as showcases for its vision, Rewilding Europe is working with the wider conservation community to create a supportive environment for rewilding to take root. An important step was made thanks to efforts of The WILD Foundation prior to and during WILD10 in October 2013 in Salamanca (Spain), where “A Vision for a Wilder Europe” was presented and signed by 10 European conservation organizations (Sylvén and Widstrand 2015). This vision was a landmark publication, for the first time addressing 10 key actions to promote a wilder Europe, many of which are now being taken forward by the various signatory organizations. WILD10 also marked the first specific seminar on rewilding in Europe, involving many different speakers and positions on this topic, further elaborating and sharing views and experiences. Since 2011, dozens of rewild-ing initiatives have been launched independent to those of Rewilding Europe. An important recent development is the launch of Rewilding Britain in June 2015, which is opening up the conservation debate in the UK and providing the inspiration for pioneering rewilding projects there. Rewilding Europe liaises closely with Rewilding Britain and other rewild-ing groups across Europe to promote alignment of rewilding approaches, taking into account the national context in which each is working. For instance, land ownership is different in many European countries; in some, land is mostly privately owned (e.g., Spain), in others, large tracts are state owned (e.g., Poland), and in still others conservation NGOs own large properties and have great rewilding possibilities (e.g., UK, Netherlands, Germany). But it is not only land tenure that is a key factor determining rewilding possibilities –user rights (hunting, grazing, fishing, logging, management) of public, communal, and state land also provide ample rewilding possibilities through engaging with local stakeholders. The rise of rewilding projects across Europe shows that nature conservation is opening up to new approaches in which the restoration of ecosystems becomes a priority alongside traditional concerns of preservation of species and habitats. It is important to promote exchange of knowledge, expertise, and experience to promote alignment and coordination in rewilding approaches and definitions. This extends to the messages rewilding proponents convey to the wider European audiences and to key stakeholder groups, such as policy makers, scientists, and practitioners. In such activities Rewilding Europe adopts a bottom-up approach, recognizing the fact that conservation is a culturally dynamic as well as a scientific and technical pursuit.

Supporting 10 Showcases across Europe

Rewilding Europe’s aim is to rewild at least 1 million hectares (2,471,053 acres) of land by 2022 through the creation of 10 wildlife and wild areas of international quality that will serve as inspirational examples of what can be achieved elsewhere (Figure 2).

In these areas, where the rewilding vision is pioneered in practice, natural processes will be allowed to play a vital role in shaping landscapes and ecosystems. Among such natural processes are flooding (including erosion and sedimentation), weather conditions (including storms, avalanches, and wind-shaped sand dunes), and natural calamities (such as natural fires and disease). The nine areas selected so far were identified on the basis of more than 30 nominations from across Europe and detailed feasibility studies on opportunities for rewilding. Rewilding Europe is working with local partner organizations to develop rewilding pilots in priority areas within these larger landscapes. Current activities include reinstating natural processes such as restoring river dynamics and flooding of former polders and floodplains; supporting wildlife revitalization through the reintroduction of species; reducing human-wildlife conflict and developing new business models with hunting associations (including wild-life breeding and no-hunting zones); and establishing natural grazing pilots with a variety of large herbivores. To support nature-based economic activities, local rewilding businesses and wildlife-watching experiences are supported – to name a few.

New, Innovative Conservation Tools

Rewilding Europe has developed three novel and innovative tools to support the on-the-ground work in these rewilding areas: (1) European Rewilding Network, (2) Rewilding Europe Capital, and (3) the European Wildlife Bank. The European Rewilding Network (ERN) is a growing network of larger and smaller areas in Europe where rewilding is a key target and takes place in line with the philosophy of Rewilding Europe. The network promotes sharing expertise and lessons, creating a rewilding movement and network across Europe. Since the launch at WILD10 in Salamanca, the ERN now counts 48 members, representing 22 European countries and a total surface of 2.5 million hectares (6,177,635 acres) (Figure 3).

Rewilding Europe Capital (REC) is Europe’s first conservation finance facility; it is a revolving fund supported by a mix of philanthropic and investment capital. Since 2013, REC has provided loans to 16 enterprises in 5 rewilding areas in order to leverage carefully defined rewilding outputs as part of a pioneer phase. During the next phase, from 2016 to 2018, REC is expected to grow further. Connected to this upscaling, REC will also extend its working sphere, not only including the Rewilding Europe areas but also the ERN member areas. The European Wildlife Bank (EWB) is a live asset-lending model designed to reintroduce and expand naturally grazing wild herbivore populations across Europe. Land owners receive herds of large herbivores in a custodianship agreement and must give back half of the herd after a five-year period, while keeping the founder herd. As an average, a well-managed herd doubles in size in five years – if the grazing area extends, the landowner keeps the herd and enters a new five-year custodianship agreement, and so on. In this way natural grazing and extension of naturally grazed land is being promoted, where the return on investment is in animals. By April 2016, the European Wildlife Bank hosted 580 animals, consisting of 50 European bison, 300 wild-living horses, and 230 tauros,* while 15 natural grazing projects started in 9 different rewilding areas.

Building Nature-Bases Economies

Rewilding Europe operates in a challenging context for rural societies in Europe. In regions where agriculture is marginal, land abandonment is resulting in an exodus of skills, experience, and energy from areas with a corresponding negative impact on local and regional economies. While Rewilding Europe is primarily concerned with nature conservation, social and economic goals are also at the heart of its strategy. We recognize that in order for conservation objectives to be achieved, we need to secure the positive engagement of local people in Europe’s rural areas as well as government policy makers at local, national, and international levels. The creation of nature-based economies in and around rewilding areas is therefore a key component of Rewilding Europe’s approach. This requires the development of businesses that have a positive relationship with wild nature and wildlife – and whose commercial success is carefully linked to those natural values. We are working to demonstrate that rewilding can generate new business opportunities, jobs, and income for society, thereby creating an alternative and competitive form of land use for local people, landowners, and communities.

Rewilding in European Policies

Rewilding needs a supportive, enabling environment. Natural value is under pressure across Europe due to economic and development pressures. In 2015, the European Commission embarked on a “fitness check” of its nature legislation. This move resulted in a campaign, supported by a petition with half a million signatories of European citizens, to maintain the legislation in its current form and focus on better implementation. As a new conservation policy vision, rewilding represents an exciting opportunity to refashion conservation for the 21st century, and with this attract new investment and generate significant social, ecological, and economic returns for the next few decades. However, any new approach also involves risk and uncertainty, and development pressures on Europe’s protected areas (called Natura 2000 sites), particularly in western Europe, have resulted in a strict interpretation of nature laws. A challenge for European policy makers is how to find spaces in nature legislation and policy that will simultaneously protect the gains of the past and provide the flexibility to allow the rewilding movement to innovate and develop. Our assessment is that spaces for innovation exist not only in medium and larger Natura 2000 sites across Europe, they can also exist by framing rewilding as a conservation agenda for the wider European countryside, including smaller and even urban areas where ecological processes can be improved. The strength of rewilding is its flexibility, which derives from its focus on “upgrading” ecosystems processes, using the past as a source of insight and inspiration rather than a template for restoration, and willingness to mix nature, society, and a nature-based economy. We have recently initiated a dialogue with policy makers, practitioners, and scientists at the European level and published a policy brief that positions rewilding in the context of European conservation policy. We are encouraged by the willingness to engage with rewilding ideas and think creatively about where supportive spaces can be developed within the constraints of law and politics. In support of this process we are forming a European-wide task force of experts to spearhead thinking in this area. The emerging message from citizens, scientists, and conservation practitioners is that we want to safeguard what we have achieved in protecting existing natural value, but we also want to reset expectations about what is possible from nature conservation policy. In summary, rewilding represents an opportunity for conservation policy to shift gears – from a focus on protecting and designating to a focus on restoration that “upgrades” ecosystems, improves network connectivity, and creates new values for people in Europe. For more information about Rewilding Europe, visit www.rewild ingeurope.com and www.facebook/rewildingeurope, or download the Policy Brief or our latest Annual Review. Note: This article is largely based on a paper prepared by both authors called “Making space for Rewilding – creating an enabling policy environment in Europe” and “Rewilding Europe’s Annual Review 2015” – both to be published in 2016.

References

Chapron, G., et al. 2014. Recovery of large carnivores in human-dominated landscapes. Science 346(6216): 1517–1519.

Deinet, S., et al. 2013. Wildlife Comeback in Europe: The Recovery of Selected Mammal and Bird Species. Final report to Rewilding Europe by ZSL, BirdLife International, and European Bird Census Council. London.

Jepson, P., and F. Schepers. 2016. Making Space for Rewilding: Creating an Enabling Policy Environment in Europe. London, Nijmegen: Rewilding Europe.

Sylvén, M., and S. Widstrand. 2015. A Vision for a Wilder Europe: Saving Our Wilderness, Rewilding Nature, and Letting Wildlife Come Back … for the Benefit of All. Retrieved from https://www.rewildingeurope.com/publications/vision-for-a-wilder-europe/.

*“Tauros” is the name of a bovine breed that resembles the original auroch (Europe’s original wild bovine), which is being bred-back from old cattle breeds in Europe that are genetically close to the auroch. See https://www.rewildingeurope.com/tauros-programme/.

FRANS SCHEPERS is cofounder and managing director of Rewilding Europe; email: fransschepers@rewildingeurope. com.

PAUL JEPSON is faculty at the University of Oxford, School of Geography and the Environment; email: paul.jepson@ouce. ox.ac.uk.